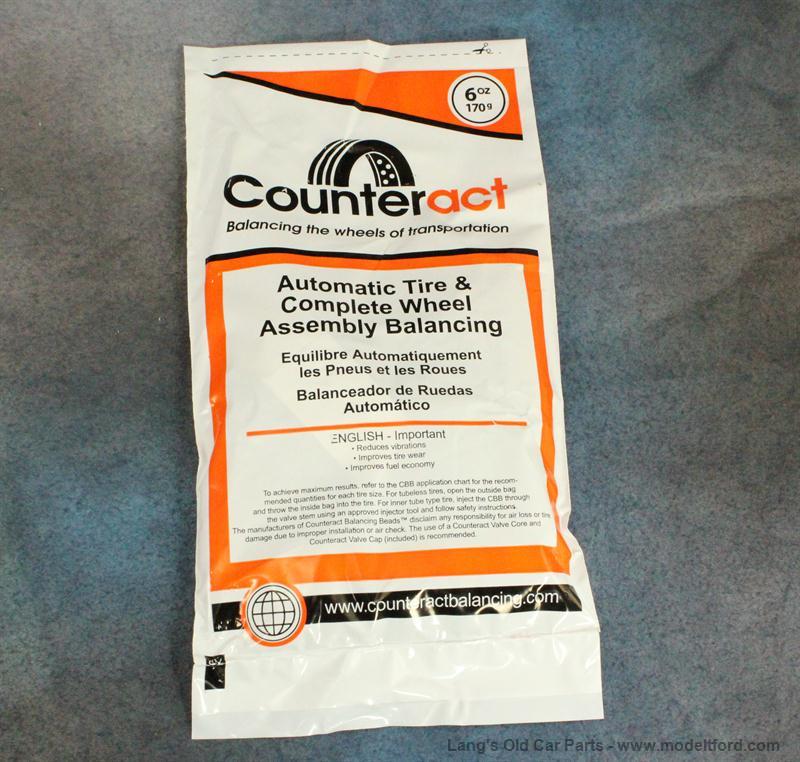

Off Road vehicles with an aggressive tire tread, add 2oz to the recommended application. ABC Balancing Beads can be installed through the valve stem. For any questions please feel free to contact us at the number located at the top of your screen.

Light Truck

6000 lbs or less

6001 lbs to 10,000 lbs

Delivery & Light Truck

10,001 lbs to 14,000 lbs

14,001 lbs to 16,000 lbs

Medium Duty Truck

16,001 lbs to 19,500 lbs

19,001 lbs to 26,000 lbs

Heavy Duty Truck & Bus

26,001 lbs to 33,000 lbs

33,001 lbs to 105,000+ lbs

Off Road and Lifted Pickups

Tire Size:

215/75R14 4oz

205/70R14 4oz

215/70R14 4oz

Tire Size:

700R15 4oz

7.50R15 6oz

8.25R15 6oz

9R15 8oz

10R15 8oz

215/80R15 4oz

195/75R15 40z

205/75R15 40z

215/75R15 4oz

225/75R15 4oz

235/75R15 4oz

245/75R15 40z

255/75R15 40z

265/75R15 40z

235/70R15 40z

245/70R15 40z

255/70R15 4oz

265/70R15 4oz

285/70R15 40z

315/70R15 6oz

245/65R15 4oz

225/60R15 4oz

325/60R15 6oz

Tire Size:

325/75R20 80z

275/65R20 6oz

275/60R20 6oz

325/60R20 6oz

255/60R20 6oz

275/55R20 4oz

285/55R20 4oz

255/50R20 4oz

285/50R20 4oz

305/50R20 6oz

325/50R20 6oz

355/50R20 6oz

325/45R20 6oz

275/40R20 6oz

315/35R20 6oz

Tire Size:

6. 5R16 4oz

7.50R16 4oz

8.25R16 6oz

1R16 8oz

215/85R16 4oz

225/85R16 4oz

245/85R16 4oz

255/85R16 4oz

265/85R16 6oz

275/85R16 6oz

205/80R16 4oz

325/80R16 6oz

175/75R16 4oz

195/75R16 4oz

225/75R16 4oz

235/75R16 4oz

245/75R16 4oz

265/75R16 6oz

285/75R16 6oz

315/75R16 6oz

215/70R16 4oz

225/70R16 4oz

235/70R16 4oz

245/70R16 4oz

255/70R16 4oz

265/70R16 4oz

275/70R16 4oz

305/70R16 4oz

315/70R16 6oz

355/70R16 6oz

365/70R16 6oz

395/70R16 6oz

195/65R16 4oz

215/65R16 4oz

225/65R16 4oz

245/65R16 4oz

255/65R16 4oz

305/65R16 4oz

345/65R16 6oz

375/65R16 6oz

215/60R16 4oz

225/60R16 4oz

235/60R16 4oz

285/60R16 4oz

255/55R16 4oz

315/55R16 4oz

345/55R16 6oz

355/55R16 6oz

375/55R16 6oz

245/50R16 4oz

Tire Size:

8R16.5 6oz

8.75R16.5 6oz

9.50R16.5 6oz

10R16.5 6oz

12R16.5 6oz

Tire Size:

235/80R17 6oz

235/75R17 6oz

245/75R17 6oz

255/75R17 6oz

245/70R17 6oz

255/70R17 6oz

285/70R17 6oz

305/70R17 6oz

315/70R17 6oz

355/70R17 6oz

255/65R17 6oz

235/65R17 4oz

245/65R17 4oz

255/65R17 4oz

265/65R17 6oz

305/65R17 6oz

375/65R17 8oz

225/60R17 4oz

235/60R17 4oz

255/60R17 6oz

275/60R17 6oz

285/60R17 6oz

225/55R17 4oz

255/55R17 4oz

275/55R17 6oz

345/55R17 6oz

255/50R17 4oz

Tire Size:

325/55R22 6oz

335/55R22 6oz

325/50R22 6oz

305/45R22 6oz

305/40R22 6oz

285/35R22 6oz

Tire Size:

8R17. 5 6oz

5 6oz

8.5R17.5 6oz

9R17.5 6oz

9.5R17.5 8oz

10R17.5 80z

11R17.5 80z

225/90R17.5 8oz

205/80R17.5 8oz

225/80R17.5 8oz

205/75R17.5 6oz

215/75R17.5 6oz

225/75R17.5 6oz

235/75R17.5 6oz

245/75R17.5 6oz

195/70R17.5 6oz

215/70R17.5 6oz

235/70R17.5 6oz

195/60R17.5 6oz

205/60R17.5 6oz

225/60R17.5 6oz

Tire Size:

7.50R18 8oz

255/70R18 6oz

285/60R18 6oz

325/60R18 6oz

375/60R18 8oz

395/60R18 8oz

255/55R18 4oz

275/55R18 4oz

285/55R18 4oz

285/50R18 4oz

375/50R18 6oz

Tire Size:

255/55R19 4oz

255/50R19 4oz

275/45R19 4oz

285/45R19 4oz

Tire Size:

325/45R24 6oz

Tire Size:

8R19.5 8oz

9R19.5 80z

18R19.5 14oz

280/75R19.5 8oz

285/75R19.5 8oz

225/70R19.5 8oz

245/70R19.5 8oz

265/70R19.5 8oz

275/70R19.5 10oz

285/70R19.5 10oz

305/70R19.5 12oz

385/65R19. 5 14oz

5 14oz

445/65R19.5 14oz

Tire Size:

7.50R20 10oz

8.25R20 10oz

9.00R20 12oz

10.00R20 12oz

11R20 14oz

12.00R20 14oz

12.5R20 14oz

14/80R20 14oz

14.00R20 16oz

365/80R20 16oz

395/80R20 16oz

Tire Size:

525/65R20.5 20oz

615/65R20.5 20oz

Tire Size:

10.00R22 12oz

1.00R22 12oz

Tire Size:

9R22.5 10oz

10R22.5 10oz

11R22.5 12oz

12R22.5 14oz

13R22.5 12oz

15R22.5 12oz

16R22.5 14oz

16.5R22.5 14oz

18R22.5 16oz

235/80R22.5 6oz

255/80R22.5 8oz

275/80R22.5 12oz

295/80R22.5 14oz

315/80R22.5 14oz

365/80R22.5 14oz

245/75R22.5 10oz

265/75R22.5 10oz

285/75R22.5 12oz

295/75R22.5 12oz

315/75R22.5 12oz

345/75R22.5 12oz

350/75R22.5 14oz

235/70R22.5 8oz

255/70R22.5 10oz

11/70R22.5 10oz

265/70R22.5 10oz

275/70R22.5 12oz

305/70R22.5 12oz

315/70R22.5 12oz

365/70R22. 5 120z

5 120z

365/65R22.5 12oz

385/65R22.5 12oz

425/65R22.5 14oz

445/65R22.5 160z

285/60R22.5 10oz

295/60R22.5 10oz

305/60R22.5 10oz

315/60R22.5 10oz

385/55R22.5 12oz

455/55R22.5 16oz

275/50R22.5 10oz

445/50R22.5 16oz

Tire Size:

1.00R24 14oz

12.00R24 14oz

14.00R24 16oz

445/70R24 16oz

495/70R24 16oz

Tire Size:

11R24.5 12oz

12R24.5 14oz

285/75R24.5 12oz

305/75R24.5 12oz

315/75R24.5 12oz

275/80R24.5 12oz

295/80R24.5 12oz

MUD TERRAIN

Tire Size:

35/12.5 R20 14oz

35/13.5 R20 14oz

36/13.5 R20 14oz

37/13.5 R20 14oz

38/13.5 R20 14oz

33/12.5 R20 12oz

37/12.5 R20 14oz

33/12.5 R22 14oz

35/12.5 R22 14oz

37/12.5 R22 14oz

36/13.5 R22 112oz

37/13.5 R22 16oz

38/13.5 R22 16oz

33/12.5 R18 12oz

34/12.5 R18 12oz

35/12.5 R18 12oz

36/12.5 R18 12oz

37/12.5 R18 12oz

42/12. 5 R18 12oz

5 R18 12oz

33/13.5 R18 12oz

36/13.5 R18 12oz

37/13.5 R18 14oz

38/13.5 R18 14oz

40/13.5 R18 14oz

35/14.5 R18 12oz

38/14.5 R18 14oz

40/14.5 R18 14oz

41/14.5 R18 16oz

33/12.5 R17 12oz

35/12.5 R17 12oz

37/12.5 R17 14oz

33/13.5 R17 12oz

36/13.5 R17 14oz

37/13.5 R17 14oz

40/13.5 R17 14oz

35/14.5 R17 12oz

31/12.5 R16 10oz

32/12.5 R16 10oz

33/12.5 R16 10oz

34/12.5 R16 10oz

35/12.5 R16 12oz

36/12.5 R16 12oz

37/12.5 R16 12oz

33/13.5 R16 10oz

36/13.5 R16 12oz

40/13.5 R16 14oz

33/14.5 R16 12oz

35/14.5 R16 12oz

36/14.6 R16 14oz

38/14.5 R16 14oz

40/14.5 R16 16oz

31/12.5 R15 8oz

32/12.5 R15 10oz

33/12.5 R15 10oz

34/12.5 R15 10oz

35/12.5 R15 10oz

36/12.5 R15 12oz

37/12.5 R15 12oz

38/12.5 R15 12oz

31/13.5 R15 8oz

33/13.5 R15 610oz

35/13.5 R15 12oz

37/13.5 R15 12oz

40/13.5 R15 14oz

31/14.5 R15 10oz

33/14. 5 R15 12oz

5 R15 12oz

35/14.5 R15 12oz

36/14.5 R15 14oz

37/14.5 R15 14oz

40/14.5 R15 14oz

Tire Size:

27/8.5R14 4oz

Tire Size:

31/10.50R16.5 6oz

33/12.50R16.5 8oz

35/12.50R16.5 8oz

37/12.50R16.5 10oz

33/14.50R16.5 10oz

35/14.50R16.5 10oz

38/15.50R16.5 12oz

33/16.50R16.5 10oz

36/16.50R16.5 12oz

40/17B16.5 14oz

44/18.50B16.5 14oz

Tire Size:

33/12.50R17 10oz

35/12.50R17 10oz

37/12.50R17 10oz

37/13.50R17 10oz

40/13.50R17 10oz

ALL TERRAIN

Tire Size:

35/12.5 R20 12oz

35/13.5 R20 12oz

36/13.5 R20 12oz

37/13.5 R20 12oz

38/13.5 R20 12oz

33/12.5 R20 10oz

37/12.5 R20 12oz

33/12.5 R22 12oz

35/12.5 R22 12oz

37/12.5 R22 12oz

36/13.5 R22 12oz

37/13.5 R22 14oz

38/13.5 R22 14oz

33/12.5 R18 10oz

34/12.5 R18 10oz

35/12.5 R18 10oz

36/12.5 R18 10oz

37/12. 5 R18 10oz

5 R18 10oz

42/12.5 R18 10oz

33/13.5 R18 10oz

36/13.5 R18 10oz

37/13.5 R18 12oz

38/13.5 R18 12oz

40/13.5 R18 12oz

35/14.5 R18 10oz

38/14.5 R18 12oz

40/14.5 R18 12oz

41/14.5 R18 14oz

33/12.5 R17 10oz

35/12.5 R17 10oz

37/12.5 R17 12oz

33/13.5 R17 10oz

36/13.5 R17 12oz

37/13.5 R17 12oz

40/13.5 R17 12oz

35/14.5 R17 10oz

31/12.5 R16 8oz

32/12.5 R16 8oz

33/12.5 R16 8oz

34/12.5 R16 8oz

35/12.5 R16 10oz

36/12.5 R16 10oz

37/12.5 R16 10oz

33/13.5 R16 8oz

36/13.5 R16 10oz

40/13.5 R16 12oz

33/14.5 R16 10oz

35/14.5 R16 10oz

36/14.6 R16 12oz

38/14.5 R16 12oz

40/14.5 R16 14oz

31/12.5 R15 8oz

32/12.5 R15 8oz

33/12.5 R15 8oz

34/12.5 R15 8oz

35/12.5 R15 8oz

36/12.5 R15 10oz

37/12.5 R15 10oz

38/12.5 R15 10oz

31/13.5 R15 8oz

33/13.5 R15 8oz

35/13.5 R15 10oz

37/13.5 R15 10oz

40/13.5 R15 12oz

31/14.5 R15 8oz

33/14. 5 R15 10oz

5 R15 10oz

35/14.5 R15 10oz

36/14.5 R15 12oz

37/14.5 R15 12oz

40/14.5 R15 12oz

Tire Size:

29/9.50R15 8oz

30/9R15 8oz

33/9.50R15 8oz

31/10.50R15 8oz

33/10.50R15 8oz

31/11.50R15 8oz

32/11.50R15 8oz

31/12.50R15 8oz

32/12.50R15 8oz

33/12.50R15 8oz

35/12.50R15 8oz

36/12.50R15 10oz

37/12.50R15 10oz

35/13.50R15 10oz

31/14.50R15 8oz

33/14.50R15 10oz

36/14.50R15 10oz

38/15.50R15 12oz

33/16.50R15 10oz

36/16.50R15 12oz

40/17R15 12oz

44/18.50R15 12oz

Tire Size:

35/12.50R20 12oz

ALL SEASON

Tire Size:

35/12.5 R20 10oz

35/13.5 R20 10oz

36/13.5 R20 10oz

37/13.5 R20 10oz

38/13.5 R20 10oz

33/12.5 R20 8oz

37/12.5 R20 10oz

33/12.5 R22 10oz

35/12.5 R22 10oz

37/12.5 R22 10oz

36/13.5 R22 10oz

37/13.5 R22 12oz

38/13.5 R22 12oz

33/12.5 R18 8oz

34/12.5 R18 8oz

35/12. 5 R18 8oz

5 R18 8oz

36/12.5 R18 8oz

37/12.5 R18 8oz

42/12.5 R18 10oz

33/13.5 R18 8oz

36/13.5 R18 8oz

37/13.5 R18 10oz

38/13.5 R18 10oz

40/13.5 R18 10oz

35/14.5 R18 8oz

38/14.5 R18 10oz

40/14.5 R18 12oz

41/14.5 R18 12oz

33/12.5 R17 8oz

35/12.5 R17 8oz

37/12.5 R17 10oz

33/13.5 R17 8oz

36/13.5 R17 10oz

37/13.5 R17 10oz

40/13.5 R17 10oz

35/14.5 R17 8oz

31/12.5 R16 6oz

32/12.5 R16 6oz

33/12.5 R16 6oz

34/12.5 R16 6oz

35/12.5 R16 8oz

36/12.5 R16 8oz

37/12.5 R16 8oz

33/13.5 R16 6oz

36/13.5 R16 8oz

40/13.5 R16 10oz

33/14.5 R16 8oz

35/14.5 R16 8oz

36/14.6 R16 10oz

38/14.5 R16 10oz

40/14.5 R16 12oz

31/12.5 R15 6oz

32/12.5 R15 6oz

33/12.5 R15 6oz

34/12.5 R15 6oz

35/12.5 R15 6oz

36/12.5 R15 8oz

37/12.5 R15 8oz

38/12.5 R15 8oz

31/13.5 R15 6oz

33/13.5 R15 6oz

35/13.5 R15 8oz

37/13.5 R15 8oz

40/13.5 R15 10oz

31/14. 5 R15 6oz

5 R15 6oz

33/14.5 R15 8oz

35/14.5 R15 8oz

36/14.5 R15 10oz

37/14.5 R15 10oz

40/14.5 R15 10oz

Tire Size:

32/9.50R16 6oz

35/10.50R16 6oz

31/12.50R16 6oz

32/12.50R16 6oz

33/12.50R16 6oz

35/12.50R16 6oz

36/12.50R16 8oz

37/12.50R16 8oz

33/14.50R16 8oz

36/14.50R16 10oz

38/15.50R16 10oz

Tire Size:

35/12.50R18 6oz

37/12.50R18 8oz

NOTE – For aggressive Mud Terrain Tires add an additional 2oz per tire application.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

%PDF-1. 6 % 10 obj /MarkInfo > /Metadata 4 0 R /OCProperties > > > ] /ON [ 5 0 R ] /Order [ ] /RBGroups [ ] >> /OCGs [ 5 0 R ] >> /Outlines 7 0 R /PageLayout /OneColumn / Pages 108 0 R /StructTreeRoot 179 0 R /Type /Catalog >> endobj 20 obj /Comments () /Company (Home) /CreationDate (D:20161011191915+03'00') /Creator /Keywords /ModDate (D:20170130141340+03'00') /Producer (Adobe PDF Library 11.0) /SourceModified (D: 20161011161206) /Subject() /Title>> endobj 3 0 obj > /Font > >> /Fields 368 0 R >> endobj 40 obj > stream 2017-01-30T14:13:40+03:002016-10-11T19:19:15+03:002017-01-30T14:13:40+03:00Acrobat PDFMaker 11 for Worduuid:9931f33d-396d-4f1e-9a3b-0216857ca5dduuid:f785dc88-9449-4c0b-9932-04cc147003af 54 application/pdf

6 % 10 obj /MarkInfo > /Metadata 4 0 R /OCProperties > > > ] /ON [ 5 0 R ] /Order [ ] /RBGroups [ ] >> /OCGs [ 5 0 R ] >> /Outlines 7 0 R /PageLayout /OneColumn / Pages 108 0 R /StructTreeRoot 179 0 R /Type /Catalog >> endobj 20 obj /Comments () /Company (Home) /CreationDate (D:20161011191915+03'00') /Creator /Keywords /ModDate (D:20170130141340+03'00') /Producer (Adobe PDF Library 11.0) /SourceModified (D: 20161011161206) /Subject() /Title>> endobj 3 0 obj > /Font > >> /Fields 368 0 R >> endobj 40 obj > stream 2017-01-30T14:13:40+03:002016-10-11T19:19:15+03:002017-01-30T14:13:40+03:00Acrobat PDFMaker 11 for Worduuid:9931f33d-396d-4f1e-9a3b-0216857ca5dduuid:f785dc88-9449-4c0b-9932-04cc147003af 54 application/pdf

0Industrial Heat Engineering; Thermal equipment; Evaporators - design; Evaporators - design; Distillation plants - design; Drying plants - design; Refrigeration plants - design; Construction materials; Heat exchangersD:20161011161206Home endstream endobj 5 0 obj > /PageElement > /Print > /View > >> >> endobj 6 0 obj > stream x\ɮ+yx xYtv`?EKH*Uδ+XөAH" PRXR)'3 PQ*'0MAi`|Fq 6-1fVpL&a0

0Industrial Heat Engineering; Thermal equipment; Evaporators - design; Evaporators - design; Distillation plants - design; Drying plants - design; Refrigeration plants - design; Construction materials; Heat exchangersD:20161011161206Home endstream endobj 5 0 obj > /PageElement > /Print > /View > >> >> endobj 6 0 obj > stream x\ɮ+yx xYtv`?EKH*Uδ+XөAH" PRXR)'3 PQ*'0MAi`|Fq 6-1fVpL&a0 Throughout the history of mankind, many objects and goods have played the role of money, and the degree of hardness / softness depended on the technological capabilities of each era. From shells, salt, livestock, silver, gold, gold-backed treasury notes to current government tenders, each new round of technological progress has allowed us to adopt a new kind of currency with its own advantages and, of course, pitfalls. By examining the history of the tools and materials used as money at different times, we can identify the characteristics that make a medium of exchange successful or unsuccessful. Without this knowledge, it is impossible to understand how Bitcoin functions and what is its role as a monetary instrument.

From shells, salt, livestock, silver, gold, gold-backed treasury notes to current government tenders, each new round of technological progress has allowed us to adopt a new kind of currency with its own advantages and, of course, pitfalls. By examining the history of the tools and materials used as money at different times, we can identify the characteristics that make a medium of exchange successful or unsuccessful. Without this knowledge, it is impossible to understand how Bitcoin functions and what is its role as a monetary instrument.

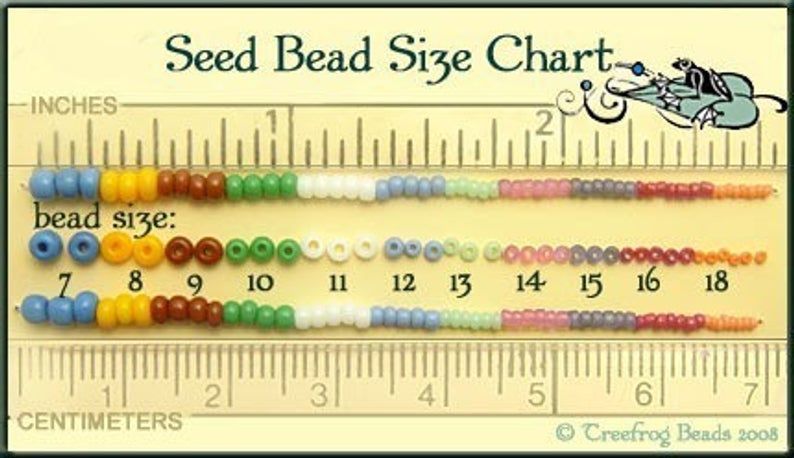

In the next chapter, we'll look at the materials and artifacts that were used as money in primitive communities, from Yap rocks and American Indian shells to African glass beads and cattle and salt. Each of these mediums of exchange performed the function of money as long as the optimum balance of reserve and inflow was maintained, and lost value when the ratio changed. The causes and mechanisms of these changes will help us understand the further evolution of money and predict what role Bitcoin can play in it. In Chapter 3, we will discuss precious metals and find out how and why gold became the main monetary metal by the end of the 19th century, when the gold standard arose. Chapter 4 is devoted to the transition to national currencies and their background, after which we will consider the invention of bitcoin and its monetary characteristics.

In Chapter 3, we will discuss precious metals and find out how and why gold became the main monetary metal by the end of the 19th century, when the gold standard arose. Chapter 4 is devoted to the transition to national currencies and their background, after which we will consider the invention of bitcoin and its monetary characteristics.

Among all the varieties of ancient money known to me, rai – round stones of Yap Island (modern Micronesia) deserve special mention. It is this system that, in terms of functional characteristics, is closest to bitcoin. Understanding how these huge limestone discs acted as a means of payment will help us understand how cryptocurrencies work. A very remarkable story about the loss of rai the status of the monetary unit will clearly show what happens when a hard currency turns into a soft one.

Rai stones - the money of the island of Yap - are large round discs with a hole in the middle. The weight of such a stone can reach four tons. Among the local rocks there is no limestone, so all the paradises were imported from the islands of the neighboring Palau or Guam archipelago. The beauty and rarity of these stones made them desirable luxury items, but they were not easy to obtain. Extraction involved exhausting labor in quarries and the transportation of solid blocks on rafts and canoes. Sometimes hundreds of workers were needed for transportation. When the next stone hit Yap, it was placed in a prominent place of honor. The owner of the stone could use it as a means of payment even without moving. It was enough to announce to all members of the tribe that the stone now has a new owner. After that, the recipient himself could pay with a stone whenever and for anything. It was simply impossible to steal the stone, since everyone on the island knew who it belonged to.

The weight of such a stone can reach four tons. Among the local rocks there is no limestone, so all the paradises were imported from the islands of the neighboring Palau or Guam archipelago. The beauty and rarity of these stones made them desirable luxury items, but they were not easy to obtain. Extraction involved exhausting labor in quarries and the transportation of solid blocks on rafts and canoes. Sometimes hundreds of workers were needed for transportation. When the next stone hit Yap, it was placed in a prominent place of honor. The owner of the stone could use it as a means of payment even without moving. It was enough to announce to all members of the tribe that the stone now has a new owner. After that, the recipient himself could pay with a stone whenever and for anything. It was simply impossible to steal the stone, since everyone on the island knew who it belonged to.

This monetary system has functioned successfully for centuries, and perhaps millennia. While remaining immobile, rai nevertheless solved the problem of exchange at a distance, since they were accepted for payment throughout the island. The different size of the stones also made it possible to solve the problem of scale. In addition, it was possible to pay off with a part of the stone. As for the issue of preserving value, it was solved by the complexity and high cost of extracting new stones, because, as we remember, it was very problematic to bring them from Palau. Therefore, the reserve of stones has always significantly exceeded any new supply in the foreseeable period. All this made rai a reliable and popular currency. In other words, they had a very high reserve-to-inflow ratio. No matter how eager the islanders were to possess stones, it was almost impossible to bring a large shipment and thereby depreciate the existing stock - at least until 1871, when an American captain named David O'Keeffe was shipwrecked off the coast of Yap Island and was rescued by local residents [9] .

The different size of the stones also made it possible to solve the problem of scale. In addition, it was possible to pay off with a part of the stone. As for the issue of preserving value, it was solved by the complexity and high cost of extracting new stones, because, as we remember, it was very problematic to bring them from Palau. Therefore, the reserve of stones has always significantly exceeded any new supply in the foreseeable period. All this made rai a reliable and popular currency. In other words, they had a very high reserve-to-inflow ratio. No matter how eager the islanders were to possess stones, it was almost impossible to bring a large shipment and thereby depreciate the existing stock - at least until 1871, when an American captain named David O'Keeffe was shipwrecked off the coast of Yap Island and was rescued by local residents [9] .

O'Keeffe dreamed of making money by collecting coconuts and selling them to coconut oil producers, but he failed to hire local helpers: the islanders were quite happy with life in their tropical paradise and did not recognize any foreign money (and simply did not see the point in them) . But O'Keefe was not going to give up. He went to Hong Kong, bought a large ship and a supply of explosives, then sailed to the shores of Palau, where he obtained several large rai using explosives and the latest tools, and returned to Yap to offer stones to the islanders in payment for coconuts. However, contrary to his expectations, the tribe was in no hurry to accept the stones, and the leader even forbade working for them, declaring that O'Keefe's stones were of no value because they got too easily. Only rai mined in the traditional way, p to volume and the blood of the Yappians could have circulated on the island. Part of the tribe did not support the leader and still gave O'Keefe a large batch of coconuts. As a result, conflict broke out on the island, and over time, the value of rai stones came to naught. Today they play a cultural and ceremonial role, and modern state money serves as the main means of payment.

But O'Keefe was not going to give up. He went to Hong Kong, bought a large ship and a supply of explosives, then sailed to the shores of Palau, where he obtained several large rai using explosives and the latest tools, and returned to Yap to offer stones to the islanders in payment for coconuts. However, contrary to his expectations, the tribe was in no hurry to accept the stones, and the leader even forbade working for them, declaring that O'Keefe's stones were of no value because they got too easily. Only rai mined in the traditional way, p to volume and the blood of the Yappians could have circulated on the island. Part of the tribe did not support the leader and still gave O'Keefe a large batch of coconuts. As a result, conflict broke out on the island, and over time, the value of rai stones came to naught. Today they play a cultural and ceremonial role, and modern state money serves as the main means of payment.

Although O'Keeffe's story is highly symbolic, he was only a harbinger of the inevitable depreciation of rai as industrial civilization advanced to Yap Island. When modern tools and industrial equipment came to the region, the cost of mining and processing stones became much cheaper. O'Keefe had many followers (local and overseas) who brought large quantities of new rai to Yap Island. Thanks to modern technology, the ratio of resource to inflow has dropped dramatically; every year more and more stones appeared on the island, and the former stock devalued. It became unwise to use rai as a long-term investment, and as a result, they gradually depreciated.

When modern tools and industrial equipment came to the region, the cost of mining and processing stones became much cheaper. O'Keefe had many followers (local and overseas) who brought large quantities of new rai to Yap Island. Thanks to modern technology, the ratio of resource to inflow has dropped dramatically; every year more and more stones appeared on the island, and the former stock devalued. It became unwise to use rai as a long-term investment, and as a result, they gradually depreciated.

The details may vary, but the overall dynamics—a sharp increase in inflows and a devaluation of the reserve—are the same for all currencies that are losing monetary status (including the collapse of the Venezuelan bolivar, which is happening before our eyes).

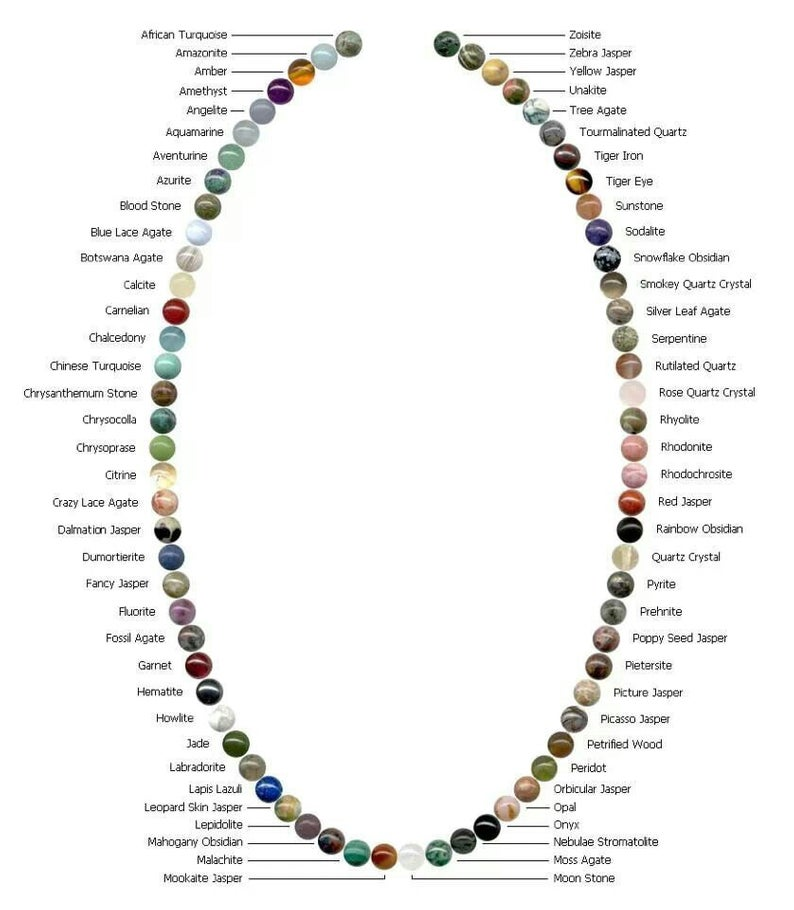

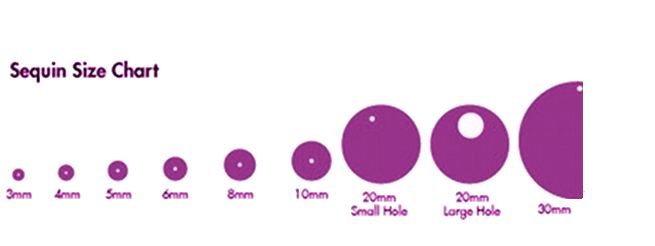

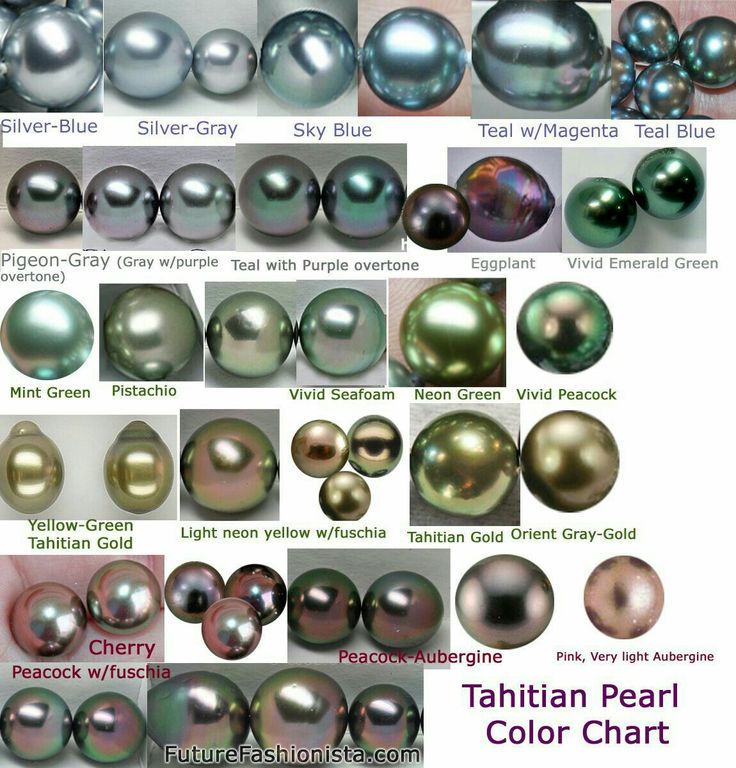

A similar story happened with agri beads, which for many centuries played the role of money in West Africa. The origin of the beads is unknown, they were presumably made from meteorites or were brought by Egyptian and Phoenician merchants. However, we know for sure that these beads were extremely highly valued in places where glassblowing was expensive or not practiced at all. Their high reserve-to-flow ratio provided them with long-term value. Being compact and expensive, the beads solved the problem of scale, since they could be assembled into chains, necklaces or bracelets. However, this solution was not ideal, since instead of one standard “currency”, the population used different types of beads. But they were comfortable to wear, which allowed them to pay anywhere. In Europe, glass beads were inexpensive and never had a monetary status, because glass production was well developed there, and if beads were used as money, glassblowers would immediately flood the market with them. In other words, they had a very low reserve-to-inflow ratio.

However, we know for sure that these beads were extremely highly valued in places where glassblowing was expensive or not practiced at all. Their high reserve-to-flow ratio provided them with long-term value. Being compact and expensive, the beads solved the problem of scale, since they could be assembled into chains, necklaces or bracelets. However, this solution was not ideal, since instead of one standard “currency”, the population used different types of beads. But they were comfortable to wear, which allowed them to pay anywhere. In Europe, glass beads were inexpensive and never had a monetary status, because glass production was well developed there, and if beads were used as money, glassblowers would immediately flood the market with them. In other words, they had a very low reserve-to-inflow ratio.

When European travelers and traders reached West Africa in the 16th century, they noticed how highly glass was valued there and began to import it in large quantities from Europe. The subsequent development of events was reminiscent of the O'Keeffe story, but given the much larger size of the region, here the process was slow and covert, and ultimately led to incomparably more serious and tragic consequences. Gradually, the Europeans managed to buy up a huge amount of African resources for beads, which cost them a few pennies themselves [10] . The European invasion of Africa eventually turned the beads from hard currency to soft currency, depriving them of their market appeal and undermining the purchasing power of their holders. The population became impoverished, and wealth accumulated in the hands of the Europeans, who could easily get any number of beads. Subsequently, the agri were nicknamed "slave beads" for the role they played in the sale of Africans on New World plantations. A single collapse of a means of payment is tragic, but at least it ends quickly and the population can trade, save and make payments in a new currency. But gradual depreciation, stretched over time, transfers the assets of the owners of the means of payment into the hands of those who can produce it at minimal cost.

The subsequent development of events was reminiscent of the O'Keeffe story, but given the much larger size of the region, here the process was slow and covert, and ultimately led to incomparably more serious and tragic consequences. Gradually, the Europeans managed to buy up a huge amount of African resources for beads, which cost them a few pennies themselves [10] . The European invasion of Africa eventually turned the beads from hard currency to soft currency, depriving them of their market appeal and undermining the purchasing power of their holders. The population became impoverished, and wealth accumulated in the hands of the Europeans, who could easily get any number of beads. Subsequently, the agri were nicknamed "slave beads" for the role they played in the sale of Africans on New World plantations. A single collapse of a means of payment is tragic, but at least it ends quickly and the population can trade, save and make payments in a new currency. But gradual depreciation, stretched over time, transfers the assets of the owners of the means of payment into the hands of those who can produce it at minimal cost. It is useful to remember this lesson when discussing the stability of government currencies in the last chapters of the book.

It is useful to remember this lesson when discussing the stability of government currencies in the last chapters of the book.

Seashells are another medium of exchange once very popular in many parts of the world, from North America to Africa and Asia. According to historical sources, the most traded currency was usually rare shells, which are difficult to obtain because they retained their value longer than the widespread species [11] . American Indians and early European colonists often used wampum shell beads for the same reasons as African agris: the shell variety was hard to come by, and the high reserve-to-inflow ratio made wampum perhaps the most reliable currency of the time. Agri shells and beads also had a common drawback - the lack of a single standard, which did not allow a uniform display of value, which hindered the development of the economy and the division of market segments. European settlers recognized wampum as legal tender from 1636, but as more British gold and silver was brought into the New World, coins became preferred over shells precisely because of their uniformity. Later, when better-equipped boats were used to catch shellfish, shells became widely available, which caused their value to drop sharply. And by 1661, they completely ceased to be considered the official currency and gradually lost their monetary status [12] .

Later, when better-equipped boats were used to catch shellfish, shells became widely available, which caused their value to drop sharply. And by 1661, they completely ceased to be considered the official currency and gradually lost their monetary status [12] .

This happened not only in North America, but everywhere where metal coins appeared. As a rule, abandoning shells and switching to a new, uniform means of payment turned out to be beneficial. In addition, with the advent of the industrial age, shellfish fishing became easier and shells completely depreciated.

Another ancient means of payment - livestock, a source of food and perhaps the most precious property of our ancestors, besides, in the literal sense, a hot commodity: if necessary, he will go the distance from the seller to the buyer. It plays the role of currency in our days; many communities use it for payments, especially dowries. However, otherwise it is not very convenient: bulky and poorly divided into small parts, and therefore does not always solve the problem of scale. Therefore, along with cattle, there was another currency - salt. It keeps well and is easily divided into any servings. These historical facts are still traced in the English language: for example, the word salary - salary - comes from the Latin word sal , that is, salt [13] .

Therefore, along with cattle, there was another currency - salt. It keeps well and is easily divided into any servings. These historical facts are still traced in the English language: for example, the word salary - salary - comes from the Latin word sal , that is, salt [13] .

With the development of technology and crafts, in particular metallurgy, mankind has developed more advanced types of money, which quickly replaced the former exchange goods. Metals proved to be a better medium of exchange than shells, beads, cattle, and salt, because they could be made into compact, uniform, and highly valuable units of exchange, which, moreover, were easily transported over any distance. Industrialization put an end to artefact money: the internal combustion engine dramatically increased labor productivity, and with it the influx of once valuable artifacts. Payment instruments, which retained their value due to their rarity, have lost their main protective mechanism. With the help of modern technology, rai stones are easily mined from the bowels of the earth, glass beads are made in any quantity, and trawlers catch tons of shells. As soon as these currencies lost their firmness, the resources of their owners were expropriated and the entire way of life of the community collapsed. The Yap chiefs who abandoned cheap O’Keeffe rai understood a simple truth that modern economists somehow fail to comprehend: money that is easy to make is not money at all, and soft currency does not make society richer. On the contrary, citizens are only getting poorer as their hard-earned savings are exchanged for something cheap and easily accessible.

With the help of modern technology, rai stones are easily mined from the bowels of the earth, glass beads are made in any quantity, and trawlers catch tons of shells. As soon as these currencies lost their firmness, the resources of their owners were expropriated and the entire way of life of the community collapsed. The Yap chiefs who abandoned cheap O’Keeffe rai understood a simple truth that modern economists somehow fail to comprehend: money that is easy to make is not money at all, and soft currency does not make society richer. On the contrary, citizens are only getting poorer as their hard-earned savings are exchanged for something cheap and easily accessible.

As the technologies used by the ancient society became more complex and metals and metal products penetrated into various spheres of everyday life, many metals began to be produced in large quantities and were in rather high demand in order to serve as a means of payment. The density of metals and their relatively high cost made them easy to transport - much easier than livestock or salt - which means they could be paid anywhere. Initially, the production of metals was complex and labor intensive, which did not allow for a quick increase in the existing reserve and gave them long-term value.

Initially, the production of metals was complex and labor intensive, which did not allow for a quick increase in the existing reserve and gave them long-term value.

Due to their physical characteristics and durability, as well as the presence of deposits, some metals were valued more than others. Iron and copper are prone to corrosion, and their ores are easy to find. These metals were produced in large quantities, which increased the stock and reduced their value. Therefore, the market value of iron and copper was relatively low, and as a means of payment they were used in small transactions. The rarer metals - gold and silver - are much more durable and virtually indestructible, and therefore quite suitable for long-term investments. For example, the longevity of gold allowed our ancestors to pass on accumulated wealth from generation to generation, thus setting new horizons for planning.

Initially, metals were bought and sold in ingots, weighing [14] . But over time, people learned to mint identical coins and indicate their weight, which eliminated the need to weigh and evaluate them with each transaction and greatly simplified the exchange. For the manufacture of coins, gold, silver and copper were most often used. Coins served mankind as the main type of money for about two and a half thousand years - from the time of the Lydian king Croesus, who was one of the first to mint them, and until the beginning of the 20th century. Gold coins were great for accumulation: they did not deteriorate, did not break, and practically did not depreciate. In addition, they were very convenient for transportation, since they contained great value with their low weight. Silver coins solved the problem of scale better than others: less expensive than gold, they were ideal for small transactions. Bronze or copper coins paid for the cheapest purchases. Coins provided mankind with standard, easily convertible units of value, which led to the emergence of large markets, a further division of labor, and an expansion of trade.

But over time, people learned to mint identical coins and indicate their weight, which eliminated the need to weigh and evaluate them with each transaction and greatly simplified the exchange. For the manufacture of coins, gold, silver and copper were most often used. Coins served mankind as the main type of money for about two and a half thousand years - from the time of the Lydian king Croesus, who was one of the first to mint them, and until the beginning of the 20th century. Gold coins were great for accumulation: they did not deteriorate, did not break, and practically did not depreciate. In addition, they were very convenient for transportation, since they contained great value with their low weight. Silver coins solved the problem of scale better than others: less expensive than gold, they were ideal for small transactions. Bronze or copper coins paid for the cheapest purchases. Coins provided mankind with standard, easily convertible units of value, which led to the emergence of large markets, a further division of labor, and an expansion of trade. Although from a technological point of view, coins are perhaps the most successful of all means of payment, they had two major drawbacks. The first is that the parallel use of two or three metals often created difficulties due to fluctuations in their prices associated with the dynamics of supply and demand. Owners of coins, especially silver coins, have been the victims of inflation more than once, when the production of the metal increased, and the demand for it fell. The second, more serious shortcoming was that rulers and counterfeiters often lowered the precious metal content of coins and depreciated them, transferring part of the purchasing power into the hands of the authorities or swindlers. The appearance of cheap impurities deprived the currency of hardness and reliability.

Although from a technological point of view, coins are perhaps the most successful of all means of payment, they had two major drawbacks. The first is that the parallel use of two or three metals often created difficulties due to fluctuations in their prices associated with the dynamics of supply and demand. Owners of coins, especially silver coins, have been the victims of inflation more than once, when the production of the metal increased, and the demand for it fell. The second, more serious shortcoming was that rulers and counterfeiters often lowered the precious metal content of coins and depreciated them, transferring part of the purchasing power into the hands of the authorities or swindlers. The appearance of cheap impurities deprived the currency of hardness and reliability.

However, in the 19th century, thanks to the development of banking and improved communication channels, it became possible to make transactions using paper money and checks, backed by the gold reserves of the treasury and banks. Thus, gold could be used in transactions of any size, and the need for other means of payment - copper and silver - practically disappeared. The gold standard has absorbed all the basic monetary qualities and capabilities. With its introduction, an unprecedented accumulation of world capital and an explosive development of trade began, because almost all the economies of the world were now united by a common, market-dictated choice of means of payment. However, there were some pitfalls here too: the centralized accumulation of gold in the vaults of banks, and later state central banks, allowed financial and government structures to issue banknotes for an amount exceeding the gold reserve. As a result, money became cheaper, and part of its value passed from the legal owners of banknotes to governments and banks.

Thus, gold could be used in transactions of any size, and the need for other means of payment - copper and silver - practically disappeared. The gold standard has absorbed all the basic monetary qualities and capabilities. With its introduction, an unprecedented accumulation of world capital and an explosive development of trade began, because almost all the economies of the world were now united by a common, market-dictated choice of means of payment. However, there were some pitfalls here too: the centralized accumulation of gold in the vaults of banks, and later state central banks, allowed financial and government structures to issue banknotes for an amount exceeding the gold reserve. As a result, money became cheaper, and part of its value passed from the legal owners of banknotes to governments and banks.

In order to understand how commodity money comes into existence, we need to take a closer look at the problem of soft currency, which we started talking about in Chapter 1. First of all, it is necessary to distinguish the market demand for a commodity (that is, for the acquisition or consumption of a commodity for its own sake) and monetary demand (need for goods as a means of exchange and accumulation of value). Every time we choose a product as a long-term investment, we thereby bring demand for it beyond the normal market and, as a result, raise the price. For example, the market demand for copper, taking into account all its industrial applications, is approximately 20 million tons per year at a price of about $5,000 per ton; hence the market is valued at $100 billion annually. Now imagine that a certain billionaire decides to store $10 billion in copper. When his agents rush to buy up 10 percent of the world copper market, there will inevitably be a rush and copper prices will rise. It would seem that the strategy of our billionaire is quite reasonable: the asset that he decided to buy will rise in price even before the purchase is completed.

First of all, it is necessary to distinguish the market demand for a commodity (that is, for the acquisition or consumption of a commodity for its own sake) and monetary demand (need for goods as a means of exchange and accumulation of value). Every time we choose a product as a long-term investment, we thereby bring demand for it beyond the normal market and, as a result, raise the price. For example, the market demand for copper, taking into account all its industrial applications, is approximately 20 million tons per year at a price of about $5,000 per ton; hence the market is valued at $100 billion annually. Now imagine that a certain billionaire decides to store $10 billion in copper. When his agents rush to buy up 10 percent of the world copper market, there will inevitably be a rush and copper prices will rise. It would seem that the strategy of our billionaire is quite reasonable: the asset that he decided to buy will rise in price even before the purchase is completed. It is logical to assume that others will also start investing in copper for the sake of increasing capital, and therefore the price will rise even more. However, even if there are those who want to buy copper, our imaginary billionaire will soon have a hard time. Rising prices will make copper mining and smelting a highly profitable business for manufacturers and entrepreneurs around the world. World reserves of copper ore are difficult to even estimate, let alone exhaust. In essence, the volumes of extraction and smelting are limited only by the amount of labor and funds invested in them. By raising costs, more valuable copper can always be produced. Thus, both prices and production volumes will rise until they satisfy the demand of monetary investors. Suppose this happens after an increase in production and smelting by 10 million tons per year at a price of $10,000 per ton. At some point, monetary demand must decline and some copper holders will want to get rid of part of the reserves in order to purchase other goods, because that was the point of their investment.

It is logical to assume that others will also start investing in copper for the sake of increasing capital, and therefore the price will rise even more. However, even if there are those who want to buy copper, our imaginary billionaire will soon have a hard time. Rising prices will make copper mining and smelting a highly profitable business for manufacturers and entrepreneurs around the world. World reserves of copper ore are difficult to even estimate, let alone exhaust. In essence, the volumes of extraction and smelting are limited only by the amount of labor and funds invested in them. By raising costs, more valuable copper can always be produced. Thus, both prices and production volumes will rise until they satisfy the demand of monetary investors. Suppose this happens after an increase in production and smelting by 10 million tons per year at a price of $10,000 per ton. At some point, monetary demand must decline and some copper holders will want to get rid of part of the reserves in order to purchase other goods, because that was the point of their investment.

What happens if monetary demand falls? It would seem that the copper market should return to its previous indicators: 20 million tons per year at a price of $5,000 per ton. But when the holders start to sell off the accumulated stocks, the price will fall well below this level. Our billionaire will suffer losses because, having provoked a rise in prices, he himself was forced to buy part of the reserves for more than $5,000 per ton, and now all of his copper will go at a price below $5,000. high prices, which means they will lose more than the billionaire himself.

This scheme applies to all consumable goods and materials, such as copper, zinc, nickel, tin or petroleum, that are primarily intended for consumption and processing, not for accumulation. The world's stocks of these commodities at any given moment are roughly equal to their production. New batches arrive without interruption and are immediately consumed. If one decides to store his savings in one of these commodities, he will buy up only a small part of the world's supply at the regular price, and then there will be a sharp rise in price that will consume his entire investment, because the buyer will have to compete with those who use this commodity in his industry. Producers' revenues will increase, and they will be able to invest in increasing production volumes, which will lead to a fall in prices and a depreciation of the savings of unlucky buyers. As a result, their capital will pass into the hands of the producers of the goods they purchased.

Producers' revenues will increase, and they will be able to invest in increasing production volumes, which will lead to a fall in prices and a depreciation of the savings of unlucky buyers. As a result, their capital will pass into the hands of the producers of the goods they purchased.

This is how any market bubble works: an increase in demand causes a sharp jump in prices, which further spurs demand, prices rise again, stimulating production, as a result, supply exceeds demand and prices plummet, punishing everyone who bought the goods at a price higher market. Investors are left with nothing, and producers and sellers of goods are enriched. Throughout human history, this has been the case with copper and most other commodities. Those who chose the product as a long-term investment were the losers: inventories devalued and savings eventually burned out. After that, the commodity returned to its usual role in the market and ceased to serve as a medium of exchange.

To become a reliable store of value, a product or object must meet two requirements: its value must increase when demand increases, but at the same time, its producers must be restrained from increasing supply, preventing prices from dropping sharply. Such an asset will reward anyone who chooses to hoard it and provide long-term profits, inevitably becoming the primary means of storage, because those who choose other options will either abandon them and follow the example of their wiser brethren, or simply go broke.

Such an asset will reward anyone who chooses to hoard it and provide long-term profits, inevitably becoming the primary means of storage, because those who choose other options will either abandon them and follow the example of their wiser brethren, or simply go broke.

The clear favorite in this competition of assets since ancient times has been gold, which maintains its monetary status thanks to two unique physical properties that distinguish it from other materials. First, gold is so chemically stable that it is almost impossible to destroy it. Secondly, gold cannot be synthesized from other materials (no matter what the alchemists say), but can only be extracted from ore, which is extremely rare on the planet.

The chemical stability of this metal means that almost all the gold ever found on earth is still in circulation or stored in various stores. Over the centuries, humanity has accumulated a gold reserve in the form of jewelry, coins and bullion; it is not consumed, does not deteriorate, and does not decrease. The inability to synthesize gold from other substances means that the only way to increase its supply is mining from the earth's interior, which is a costly, toxic and not always successful process. Mankind is obsessed with the gold rush of the millennium, but it is getting less and less. Therefore, the current world gold reserve is the result of thousands of years of production, significantly exceeding the annual inflow. According to statistics, over the past 70 years, the annual increase in gold reserves has consistently been about one and a half percent and has never exceeded two percent.

The inability to synthesize gold from other substances means that the only way to increase its supply is mining from the earth's interior, which is a costly, toxic and not always successful process. Mankind is obsessed with the gold rush of the millennium, but it is getting less and less. Therefore, the current world gold reserve is the result of thousands of years of production, significantly exceeding the annual inflow. According to statistics, over the past 70 years, the annual increase in gold reserves has consistently been about one and a half percent and has never exceeded two percent.

Fig. 1. World gold supply and annual increase [15]

To better understand the difference between gold and any consumer good, let's imagine the effect of a sharp increase in demand, leading to a rise in prices and a doubling of annual production. In the case of consumer goods, a doubling of the inflow would quickly outstrip the amount of stock available, causing prices to collapse and reserve holders to lose their investment. As for gold, the price jump due to the doubling of annual production will be insignificant, that is, from 1.5 to 3 percent. If new production volumes are maintained, inventories will grow faster, making further increases less significant. But for gold mining, such a scenario is unacceptable, its volumes and rates still do not allow a significant impact on the market.

As for gold, the price jump due to the doubling of annual production will be insignificant, that is, from 1.5 to 3 percent. If new production volumes are maintained, inventories will grow faster, making further increases less significant. But for gold mining, such a scenario is unacceptable, its volumes and rates still do not allow a significant impact on the market.

In these parameters, only silver comes close to gold with a historical growth rate of about 5-10 percent and a current annual increase of about 20 percent. This indicator is higher than that of gold for two reasons. First, silver can still corrode and is used for industrial purposes, which means that its reserves are not as large compared to the annual increase as gold reserves. Secondly, silver is more often found in the bowels of the earth, and it is easier to smelt it. Due to the second highest reserve-to-inflow ratio, as well as a lower price per unit weight than gold, silver served for millennia as a settlement in relatively small transactions and functionally supplemented gold, which was inappropriate to be divided into small units due to its high value. The introduction of the international gold standard, which made it possible to make payments using paper money of any denomination, backed by a gold reserve, leveled the monetary role of silver. And over time, it became an industrial metal and fell relative to gold in price. Of course, in sports, runners-up are still awarded a silver medal, but in the competition of currencies, silver did not just “come second” but lost out hopelessly to gold when 19th-century technology made it possible to make payments without the need to use the means of payment itself.

The introduction of the international gold standard, which made it possible to make payments using paper money of any denomination, backed by a gold reserve, leveled the monetary role of silver. And over time, it became an industrial metal and fell relative to gold in price. Of course, in sports, runners-up are still awarded a silver medal, but in the competition of currencies, silver did not just “come second” but lost out hopelessly to gold when 19th-century technology made it possible to make payments without the need to use the means of payment itself.

This is why the silver bubble has burst many times and will burst again if it inflates: as soon as significant funds are invested in silver, producers easily increase supply and thereby destroy prices, depriving investors of their capital. The most famous example of the soft currency trap in modern history has to do with silver. In the late 1970s, billionaire brothers William and Nelson Hunt decided to remonetize silver and began buying it up, causing prices to skyrocket. They believed that as the metal became more expensive, there would be more and more people willing to buy it, prices would rise even more, and as a result, silver would again become popular as a means of payment. However, no matter how much money the Hunt brothers invested in their venture, they still could not keep up with the explosive growth in supply: silver producers and holders literally flooded the market with metal. In the end, prices collapsed and the brothers lost more than a billion dollars - probably the largest amount in the history of mankind that had to be paid to understand a simple truth: not all that glitters is gold, but the ratio of reserve and inflow is the most important indicator for means of payment [16] .

They believed that as the metal became more expensive, there would be more and more people willing to buy it, prices would rise even more, and as a result, silver would again become popular as a means of payment. However, no matter how much money the Hunt brothers invested in their venture, they still could not keep up with the explosive growth in supply: silver producers and holders literally flooded the market with metal. In the end, prices collapsed and the brothers lost more than a billion dollars - probably the largest amount in the history of mankind that had to be paid to understand a simple truth: not all that glitters is gold, but the ratio of reserve and inflow is the most important indicator for means of payment [16] .

Fig. 2. World reserve in relation to the annual volume of production [17]

It is precisely due to the consistently low inflow of gold that it was possible to maintain its monetary status throughout the history of mankind and maintain it today, since central banks continue to store its significant reserve to provide paper of money. The official reserves of central banks amount to about 33 thousand tons, or a sixth of the total volume of all gold mined in the world. The high reserve-to-inflow ratio makes gold the lowest 9 commodity.0038 price elasticity of supply, that is, an indicator of the percentage change in supply as a result of price changes. Considering that the current gold reserve is the result of millennia of production, a 90,038 x 90,039 percent increase in the price may cause some increase in production, but it will be insignificant compared to the reserves already accumulated. For example, in 2006, spot prices rose 36 percent. In the case of any other resource, this would inevitably lead to an increase in production, a glut of the market and a collapse in prices. However, in 2006 the volume of gold production was 2370 tons - 100 tons less than in 2005 - and decreased by another 10 tons in 2007. New supply was 1.67 percent of available stock in 2005, 1.58 percent in 2006, and just 1.54 percent in 2007.

The official reserves of central banks amount to about 33 thousand tons, or a sixth of the total volume of all gold mined in the world. The high reserve-to-inflow ratio makes gold the lowest 9 commodity.0038 price elasticity of supply, that is, an indicator of the percentage change in supply as a result of price changes. Considering that the current gold reserve is the result of millennia of production, a 90,038 x 90,039 percent increase in the price may cause some increase in production, but it will be insignificant compared to the reserves already accumulated. For example, in 2006, spot prices rose 36 percent. In the case of any other resource, this would inevitably lead to an increase in production, a glut of the market and a collapse in prices. However, in 2006 the volume of gold production was 2370 tons - 100 tons less than in 2005 - and decreased by another 10 tons in 2007. New supply was 1.67 percent of available stock in 2005, 1.58 percent in 2006, and just 1.54 percent in 2007. Even a 35% increase in prices may not lead to a noticeable increase in gold production and supply in the market. According to the US Geological Survey, the most significant annual increase in gold production was recorded in 1923 and amounted to about 15 percent. At the same time, the total world gold supply increased by only 1.5 percent. Even if production were to double, the probable stock increase would be no more than 3-4 percent. The most dramatic increase in stock occurred in 1940, when it reached almost 2.6 percent. The annual increase in stocks has never exceeded this figure, and never since 1942 has it exceeded 2 percent.

Even a 35% increase in prices may not lead to a noticeable increase in gold production and supply in the market. According to the US Geological Survey, the most significant annual increase in gold production was recorded in 1923 and amounted to about 15 percent. At the same time, the total world gold supply increased by only 1.5 percent. Even if production were to double, the probable stock increase would be no more than 3-4 percent. The most dramatic increase in stock occurred in 1940, when it reached almost 2.6 percent. The annual increase in stocks has never exceeded this figure, and never since 1942 has it exceeded 2 percent.

As the production of metals developed, the ancient civilizations of China, India and Egypt used copper and then silver as a means of payment, since both metals were relatively difficult to mine and smelt at that time, but they were easy to transport in the form of coins or ingots, retain their value for a long time. Gold was highly valued in these civilizations, but due to its rarity, it could not serve as a generally accepted medium of exchange. The first gold coins were minted in Greece, the cradle of Western civilization, during the reign of King Croesus. This revitalized world trade, because in view of the widespread popularity of gold, the new coins quickly took root and spread widely. Since then, many events in our history have been closely intertwined with the reliability of the currency. Human society has always flourished where hard currency was used, while the wrong choice of monetary units often coincided with the decline of civilization and the collapse of society.

The first gold coins were minted in Greece, the cradle of Western civilization, during the reign of King Croesus. This revitalized world trade, because in view of the widespread popularity of gold, the new coins quickly took root and spread widely. Since then, many events in our history have been closely intertwined with the reliability of the currency. Human society has always flourished where hard currency was used, while the wrong choice of monetary units often coincided with the decline of civilization and the collapse of society.

ROME: GOLDEN AGE AND DECLINE

In the Roman Republic, the denarius was in circulation - a silver coin weighing 3.9 grams, but over time, gold became the most valuable means of payment in the civilized world and gold coins became widespread. Julius Caesar, the last dictator of the Roman Republic, introduced the aureus, a gold coin weighing 8 grams. Aureuses were accepted for payment throughout the Mediterranean, which contributed to the development of crafts and trade in the Old World. Rome maintained economic stability for 75 years, even as the political chaos caused by the assassination of Caesar and the transformation of the Republic into an empire under his successor, Octavian Augustus, continued. The era of prosperity lasted until the accession to the throne of the infamous emperor Nero, who introduced the practice of "circumcision of coins", when the money seized from the population was melted down into coins with a lower content of gold or silver.

Rome maintained economic stability for 75 years, even as the political chaos caused by the assassination of Caesar and the transformation of the Republic into an empire under his successor, Octavian Augustus, continued. The era of prosperity lasted until the accession to the throne of the infamous emperor Nero, who introduced the practice of "circumcision of coins", when the money seized from the population was melted down into coins with a lower content of gold or silver.

As long as Rome managed to conquer new lands, legionnaires and emperors squandered their spoils with pleasure, and emperors even bought people's love by artificially lowering the price of grain and other essential goods, or even giving them away for free. Instead of working in the fields, many peasants abandoned their farms and moved to Rome for a better share. Over time, there were no rich lands around Italy, and the habit of luxury and spending on a huge army required new sources of replenishment of the treasury, in addition, the number of idle people living from the bounties of the emperor increased.