Changing a bike tire after getting a flat is a relatively easy fix—as long as you know how to handle it. Whether you ride on smooth pavement, rough gravel, or rocky singletrack trails, it’s bound to happen eventually, so you might as well prepare yourself with both the necessary tools and the bike repair knowledge you need address the problem.

Below, we detail everything you need to know about how to change a bike tire, including the bike tire repair tips you need to succeed.

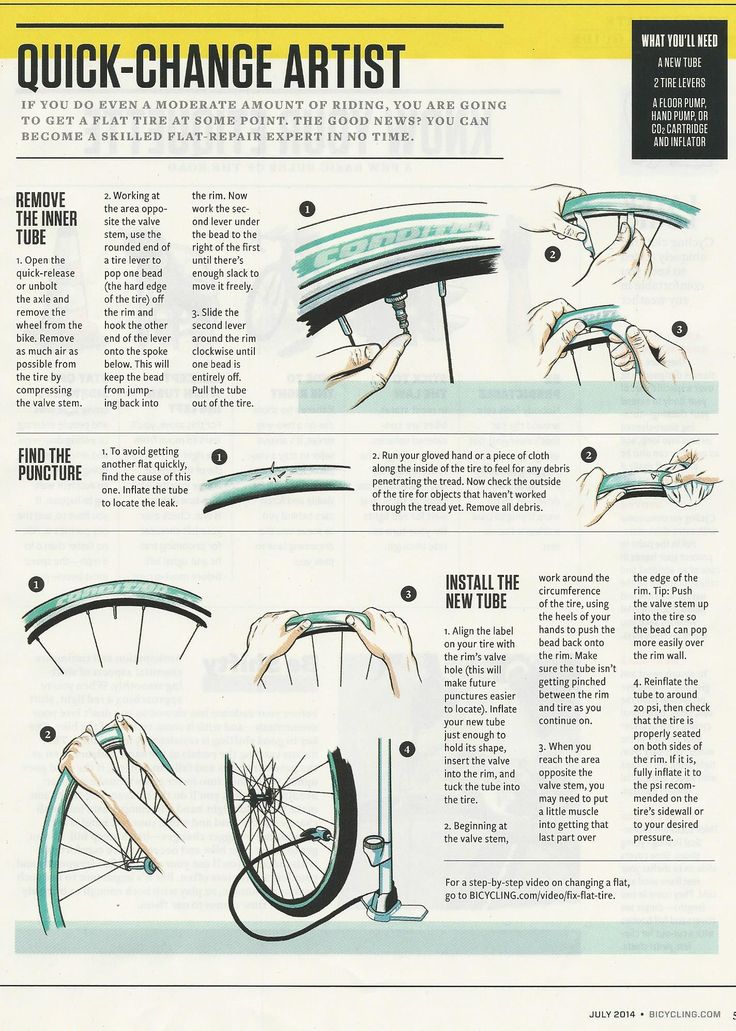

First things first though—for tools, you should always carry tire levers, a correctly-sized spare tube, and an inflation device, be it a mini pump or CO2 cartridge. You may also want to consider a patch kit or tire plug, which can come in handy for certain riders. And if you run tubeless tires, scroll down to skip to the tubeless section. When you’re ready to go, here’s your step-by-step guide.

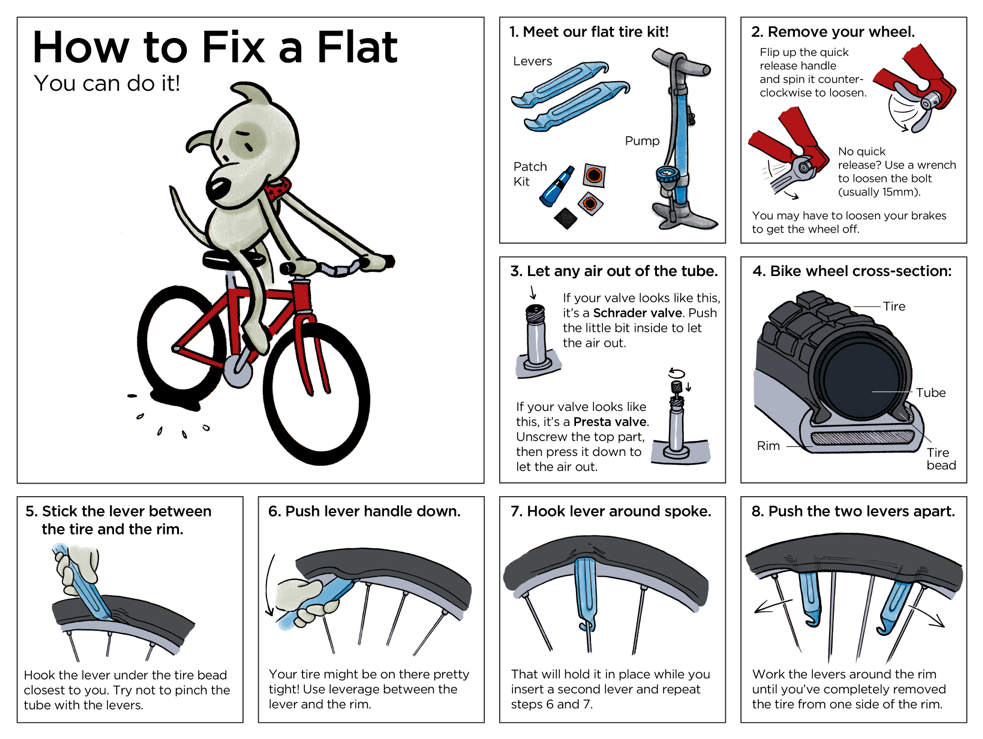

Start by removing the wheel. Keep your bike upright, and if it’s a rear-wheel flat, shift your drivetrain into the hardest gear. If your bike has rim brakes, which many bikes still do, you may also need to loosen the brake.

Next, position yourself on the non-drive side of your bike (opposite the chain) and either open the quick release or unthread the thru-axle to remove the wheel.

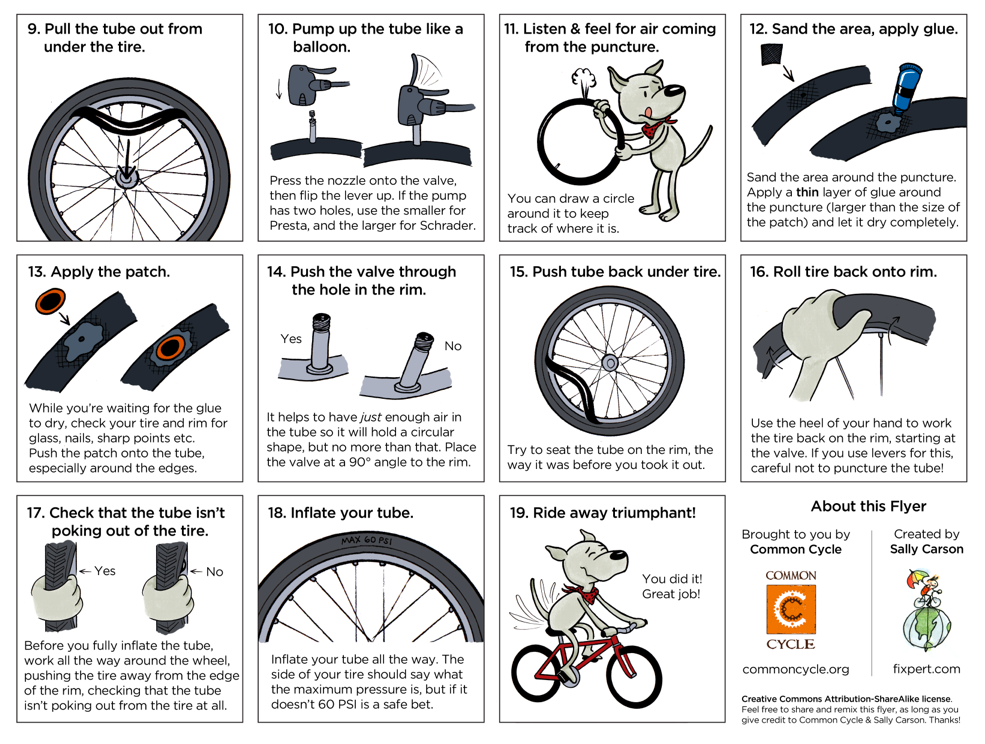

Now you can remove the tire. Hook the rounded end of one tire lever under the bead (the outer edge) of the tire to unseat it. Fix the other end to a spoke to hold the lever in place and keep the unseated tire from popping back into the rim. Then hook the second lever under the bead next to the first, pushing it around the rim clockwise until one side of the tire is off. You don’t need to completely remove the tire.

Once the tire is loose, pull out the old tube (if applicable) and look for the source of the flat, which could be a thorn, piece of glass, or some other sharp object. Carefully run your fingers along the inside of your tire and rim, making sure nothing sharp is left behind; otherwise, you risk getting another flat. Also inspect the outside of the tire, again looking for any foreign object that might still be stuck in the rubber.

Carefully run your fingers along the inside of your tire and rim, making sure nothing sharp is left behind; otherwise, you risk getting another flat. Also inspect the outside of the tire, again looking for any foreign object that might still be stuck in the rubber.

If you’re using tubes and want to do a little detective work, pump some air into the old one to find the leak. Two holes side by side indicate a pinch-flat, where the tube gets pinched between the tire and rim. A single hole is a sign that your flat was most likely caused by a sharp object. By lining the tube up with the tire using the valve as a point of reference, you can double check the area where the hole is to ensure the culprit is removed.

If you’re the thrifty type who likes to reuse old tubes, or if you’ve gotten multiple flats on your ride and have no more spares, then you can patch your tube with a patch kit. If you have a new tube, skip to the next section.

Start by cleaning the punctured area and roughing the surface with an emery cloth. For a glueless patch, simply stick it over the hole and press firmly. For a patch that requires glue, add a thin layer of glue to the tube and patch. Wait for the glue to get tacky, then apply the patch and press firmly until it adheres.

If you prefer to reuse old tubes or ran out of spares, you can try to patch the hole with a patch kit.

Katja Kircher//Getty ImagesNow inflate your new or patched tube just enough so that it holds its shape. This makes it easier to place inside the tire. Next, with the valve stem installed straight through the rim’s valve hole, position the tube inside the tire. Work the tire back onto the rim with your hands by rolling the bead away from yourself. Try not to use levers to reseat the tire, as you could accidentally puncture your new tube. When you get to the valve stem, tuck both sides of the tire bead low into the rim and push upward on the stem to get the tube inside the tire.

Check to make sure the tire bead isn’t pinching the tube by gently pushing the tire to the side as you work your way around the rim. Then inflate to the appropriate PSI and check that the bead is seated correctly.

$50 at Amazon

Credit: Silca$8 at Amazon

$6 at Amazon

Credit: Park Tool$40 at Walmart

Credit: REIIf everything looks good, reattach your wheel, making sure the quick release or thru-axle lever is on the opposite side of your drivetrain.

If you had a rear-wheel flat, lay the top of the chain around the smallest cog on your cassette and carefully push the wheel back into the frame. Close your quick release (and rim brakes if applicable) or insert the thru-axle back into the frame and hub and thread it closed.

Close your quick release (and rim brakes if applicable) or insert the thru-axle back into the frame and hub and thread it closed.

Finally, lift the rear wheel and spin your cranks once to make sure everything is back in place and operating smoothly. If all is good to go, get back on your bike and enjoy the rest of your ride.

Trevor Raab

For tubeless setups—all but standard in mountain biking and becoming increasingly popular on gravel, cyclocross, and even some road bikes—your sealant should do the trick without you even realizing it. Be sure to check your sealant regularly (about every three to six months) to make sure the tire has enough and that it hasn’t dried out.

But in the event of a bigger puncture or side-wall tear, you may need a tire plug to stop air loss. Plug kits come with a small strip of rubber and an insertion device, which allow you to plug the hole without even removing the wheel. Once you find the puncture and insert the rubber plug, re-inflate your tire to the appropriate pressure to see that it’s holding air. If so, start riding again, and check the repair every so often to make sure it’s holding fast. You could also add more sealant, but you’d need to carry a valve core removal tool and a small bottle of sealant.

Once you find the puncture and insert the rubber plug, re-inflate your tire to the appropriate pressure to see that it’s holding air. If so, start riding again, and check the repair every so often to make sure it’s holding fast. You could also add more sealant, but you’d need to carry a valve core removal tool and a small bottle of sealant.

Trevor Raab

If air loss is coming from a puncture bigger than a plug fix, you could try a patch or a boot on the tire. But fair warning: It’ll likely be difficult to get a patch to adhere to your sealant-coated tire without thoroughly cleaning the area. Adding more sealant or a patch could create another problem, too, by letting all the air out and breaking the seal between the rim and tire. It’ll likely be difficult to reseat the tire bead onto the rim on the spot. The easiest way to ensure your tire holds air at this point is to simply use a spare emergency tube to get through the ride and address it at home or at a bike shop.

$155 at Trek Bikes

$62 at Amazon

Keep It Clean

$10 at notubes.com

Precisely measure sealant and install with no mess.

Mid-Ride Repair

$60 at dynaplug.com

Brass-tipped plugs make fixing bigger punctures easy.

Jessica Coulon

Service and News Editor

When she’s not out riding her mountain bike, Jessica is an editor for Popular Mechanics. She was previously an editor for Bicycling magazine.

Home / Selle Anatomica Blog / What to Do About Fixing a Flat Bike Tire While out on a Ride

July 15, 2020

It’s a nightmare scenario for any cyclist: You’re halfway into a 50-mile ride when you suddenly begin to feel your wheel rumbling against the pavement. You pull off to the side to examine your tire, and your fears are confirmed. It’s a flat.

You pull off to the side to examine your tire, and your fears are confirmed. It’s a flat.

Now, if you had come prepared with the right supplies and experience fixing a flat bike tire, this would only be a minor nuisance. But as it is, you have neither, and now you’re stuck 25 miles from your car with no easy way to get back.

Most likely, you’d like to avoid this situation. And, since your chances of evading a flat tire are slim to none, it’s best to prepare yourself for the inevitable. Here again, our friend and cycling mentor Coach Darryl comes to save the day.

First things first—let’s get our terms straight.

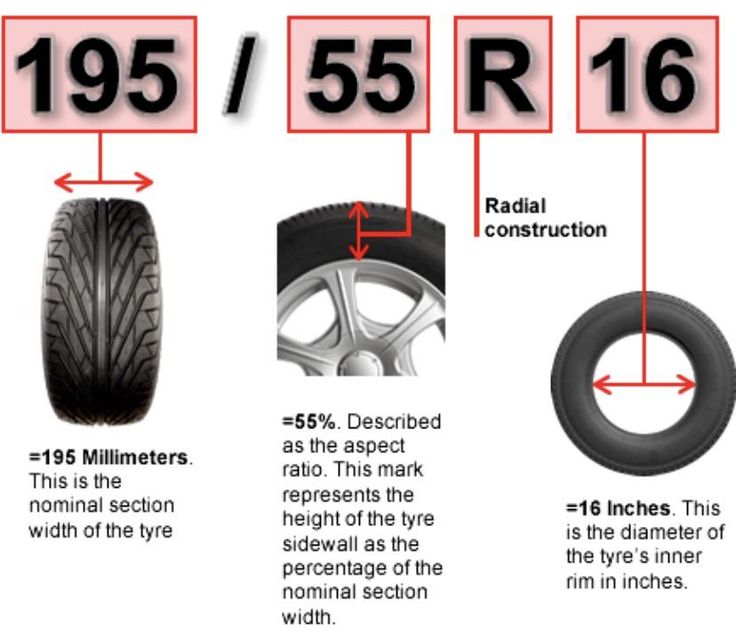

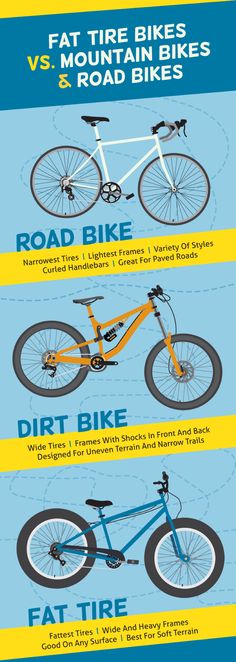

“Everybody calls it a flat tire and it isn’t,” says Coach Darryl. “It’s actually a flat tube.” Unless you’re riding the rare tubeless road bike wheels or a fat-tired mountain bike, you’re going to be changing the tube on the inside of the tire, not the tire itself.

So why do these tubes go flat with that protective layer of thick rubber tire around them? When road cycling, Darryl notes, the culprit is usually a construction staple or wire, though sometimes it can be glass, a rock or just a big bump.

You’re most likely to have to fix a flat bike tire — or rather inner a flat tube — when it’s getting old, after the first 1,000 or 2,000 miles. As your narrow road tires wear down, the contact surface (where the tire touches the road) expands from a narrow point to a surface roughly 30% wider than it was. This wider contact area makes it that much easier to pick up a sharp object from the road. The tire also grows thinner, providing less of a protective barrier for the tube.

Occasionally, though, you can get a bad tire or tube (or you put the new one in wrong — we’ll get to that). If that’s the case, you’ll know it quickly, probably on the first ride. For this reason, Darryl recommends giving yourself a 10-day lead time to try out new tires before a big ride.

Bicycle flats are a fact of cycling life. In fact, you may get more than one on a long ride. Darryl once had six in one 25-mile ride. So, yeah, Coach always comes prepared.

He recommends bringing two spare tubes on a 30-to-45-mile ride, a third if you’re going more than 50 miles, and a fourth if you’re going over 100. You can stow these last two in your jersey pockets.

You can stow these last two in your jersey pockets.

Beyond the tubes, you should also bring several CO2 cartridges that you can use to refill your tire in a matter of seconds. Without these, you’re cranking a hand pump 200-plus times for several minutes. Yes, that’s as exhausting as it sounds. If you’re already invested in a long ride, you do not want to expend extra energy fixing a flat bike tire.

Do bring a hand pump as a backup, along with two valve adapters for your CO2 tanks and two tire levers (small plastic "tire irons” for prying the tire off the rim).

With the right equipment and a little know-how, you can change a flat bike tire and be back on your bike in 10 minutes. Here’s the step-by-step guide.

This should be the easy part, as most wheels these days are quick-release or through-axle (depending on your brake type). If your flat is on the back, though, be sure to change your gear to the smallest cog, furthest from the bike frame. Your derailleur will naturally spring to this position when you remove the chain, so that’s where you want it to be to make it easier to get the chain back on the wheel when you’re finished.

Your derailleur will naturally spring to this position when you remove the chain, so that’s where you want it to be to make it easier to get the chain back on the wheel when you’re finished.

Once you have the wheel off the bike, let any remaining air out of the tube so it’s easier to detach from the rim. With the air out, you’ll need your tire levers to remove the tire.

Starting at the opposite side of the valve stem, carefully use the pointed end of a tire lever to pry the tire and tube loose from the rim. If you encounter any resistance, use a second tire lever about three inches from the first, then pry at both points.

As it begins to separate, slowly move the tire lever around the tire, gently prying as you go, until you have the tire completely removed from the wheel.

Before you completely remove the flat tube, you need to find the hole. Otherwise, the object might still be in your tire, ready to puncture your new tube when you get back on the bike.

Starting furthest from the valve stem, pull the tube out of the tire all the way, leaving just 2 or 3 inches on either side of the valve. Once you find the hole, you can then line it up with the tire to see if the cause of your flat is still lodged there. Finding the cause is essential to ensure you fix your flat bike tire once from the initial cause.

With the flat tube hanging partially out, use a hand pump to blow it up just enough to hear where the air is leaking. If you have trouble hearing it, put your hand or your face close to the tube to feel the air seeping out. Darryl notes that, if you’re fairly certain that a bump was a cause, rather than something sharp, you can skip this step.

When you find the hole, line it up with the tire to find the culprit and remove it. In most cases, Coach Darryl says the tire will be ready to hold a new tube. In the rare instance that you have a damaged side wall, though, you can use an old piece of tire or even a folded dollar bill to cover the hole and prevent the new tube from forcing its way through and going flat. This isn’t a replacement for a new tire, mind you, but just enough to get you home or to a bike shop.

This isn’t a replacement for a new tire, mind you, but just enough to get you home or to a bike shop.

After you’re sure there’s nothing left in your tire to ruin your new tube, you can completely remove the old one. Before you begin to put the new tube in, blow it up just enough to give it its normal shape. This will keep it from getting twisted or folded when you seat it inside the tire.

Once it’s partially blown up, start by seating the valve stem where it fits, then work your way around from both sides of the valve to get the tube all the way inside the tire.

This is the hardest part of repairing a flat bicycle tire. You’ll start at the valve again here, pushing it up from the inside of the tire so that it pushes the tire higher than it would normally be on the road. This will give you enough clearance to get the tire around the rim first at the valve stem.

Now work your way around from both sides of the stem so that you’ll finish at the farthest point from it. Those last 8 inches or so are going to be the most difficult, and Darryl recommends keeping your gloves on and using your palms (not your thumbs) to push the tire onto the wheel. The hands are far stronger than the thumbs, and the gloves will protect your palms.

Those last 8 inches or so are going to be the most difficult, and Darryl recommends keeping your gloves on and using your palms (not your thumbs) to push the tire onto the wheel. The hands are far stronger than the thumbs, and the gloves will protect your palms.

Although some people use their tire levers to get those last few inches around, Coach Darryl cautions against this because you can inadvertently pinch your tube in the process.

It’s important not to rush past this part and start blowing up your tire. Slowly examine all the way around the wheel on both sides, looking for any sign that the tire isn’t seated right. There should be a ridge about 1/8 of an inch away above the rim all the way around. If this is too far out at any point or you see any tube sticking out around the edges, you need to adjust the tire.

Again, this is where those small CO2 cartridges will come in handy to save you time and effort. But be careful — these cartridges fill your tire so quickly that it’s easy to overfill and pop your tube. (Keep in mind, also, that you’ll probably need to refill the tire again when you get home, since the smaller CO2 molecules will leak out more quickly.)

But be careful — these cartridges fill your tire so quickly that it’s easy to overfill and pop your tube. (Keep in mind, also, that you’ll probably need to refill the tire again when you get home, since the smaller CO2 molecules will leak out more quickly.)

Attach the cartridge to the adaptor valve (the piece that connects it to the valve on the wheel), screwing it all the way in. Position the valve on your wheel toward the ground so you can apply pressure to the valve and not leak any CO2. Then tighten the other end of the valve adapter all the way onto the valve on the tire.

Unscrew the tank just enough to release the CO2 into your tire, while holding your hand on the tire to check the pressure as it fills. (The tanks frequently have more CO2 than will fit in your tire, so you can pop your new tube if you’re not careful.) As soon as your tire is full enough, tighten the tank back down to stop the air flow.

Give everything one more check to make sure the tire is seated correctly with no tube sticking out. If everything looks good, put your wheel back on your bike and you’re ready to ride.

If everything looks good, put your wheel back on your bike and you’re ready to ride.

And, finally, try the process of fixing a flat bike tire from the comfort of your home before you attempt it on the road. It’s best to get used to the process before you find yourself threatened with sunset or bad weather.

You can find more insights from Coach Darryl over at his website.

Share:

Please enable JavaScript to view the comments powered by Disqus.

Tire failures can be caused by mechanical damage and manufacturing defects. Mechanical damage includes punctures and cuts caused by foreign bodies that have entered the tire. The following damages are the result of manufacturing defects: stratification of the thread, rupture of the thread, rupture of the seam at the single-tube, delamination of the tread.

Significant damage penetrating the outer surface of the tire is easily detected by inspection. Other damage is determined by inspecting the tire after it has been removed from the wheel rim. To speed up the location of small punctures, in which the air from the chamber is released gradually, the tire mounted on the wheel is immersed in water. At the puncture site, traces of air escaping from the tire will be visible. It is necessary to immerse not the entire wheel in water, but only part of the tire so that the surface of the water barely covers the inner surface of the rim.

Other damage is determined by inspecting the tire after it has been removed from the wheel rim. To speed up the location of small punctures, in which the air from the chamber is released gradually, the tire mounted on the wheel is immersed in water. At the puncture site, traces of air escaping from the tire will be visible. It is necessary to immerse not the entire wheel in water, but only part of the tire so that the surface of the water barely covers the inner surface of the rim.

Having found the place of the puncture, mark it on the tire with an indelible pencil, remove one edge of the tire from the rim and remove the chamber from under the tire. Having slightly pumped up the chamber, they find the puncture site by ear or by immersion in water and mark it with a pencil, and the chamber is freed from air. At the puncture site, the surface of the chamber is cleaned with a rasp, a file with a large notch or sandpaper with a large grain. On a separate piece of rubber 1-1.5 mm thick (cut from the old chamber), a surface equal to the section of the cleaned surface of the chamber is cleaned, and a patch is cut out of it with scissors, giving it a round or oval shape. From the camera and the patch, remove the dust and traces of emery remaining after stripping with a brush or a clean rag. A thin layer of rubber adhesive is applied to the surface of the chamber and the patch. The glue is allowed to dry for 15-20 minutes, and then a second layer is applied, which is also allowed to dry. After drying, the patch is applied to the damaged area of the camera, pressed tightly and rolled with a roller or lightly pierced with a wooden hammer, placing the camera on the palm of the hand.

From the camera and the patch, remove the dust and traces of emery remaining after stripping with a brush or a clean rag. A thin layer of rubber adhesive is applied to the surface of the chamber and the patch. The glue is allowed to dry for 15-20 minutes, and then a second layer is applied, which is also allowed to dry. After drying, the patch is applied to the damaged area of the camera, pressed tightly and rolled with a roller or lightly pierced with a wooden hammer, placing the camera on the palm of the hand.

If the chamber has large gaps that are difficult to seal; the best way is to repair by inserting a piece of the old chamber with the same cross-sectional profile. To do this, a piece with a length of at least 120 mm is cut out from the repaired chamber, on which there is a gap. A piece 60–100 mm longer is also cut out of the old chamber (an allowance of 30–59 mm for each joint).

Gluing joints is most conveniently done using two mandrels, which are (Fig. 68 a) segments of a thin-walled steel pipe, the diameter of which is selected so that the chamber to be glued is put on the mandrel with a slight tension. The length of each mandrel is taken equal to 80-100 mm. The wall of the mandrel is cut through along the generatrix of the cylinder.

The length of each mandrel is taken equal to 80-100 mm. The wall of the mandrel is cut through along the generatrix of the cylinder.

The end 1 of the rubber tube of the mating chamber is first passed inside the mandrel 2, and then turned inside out and pulled on the mandrel so that the latter is under the lapel. The same is done with the end 6 of the inserted piece of the chamber and the second mandrel 7. (Fig. 68 b). The end of the chamber, which will be internal after gluing, is turned out again with the outer surface up.

Fig. 68. Docking chamber

The length of the lapels must be equal to the allowance provided for gluing.

The outer surface 3 of the first end and the turned-out inner surface 4 of the second end of the chamber are thoroughly cleaned. An even layer of rubber adhesive is applied to the cleaned surfaces, and after drying, a second layer is applied, which is also allowed to dry for 15-30 minutes. After that, the ends of the chamber and the insert are joined end-to-end, and with the help of a thin wooden plate 5 placed under the lapel of the rubber tube, it is carefully turned back so that it lies on the surface of the second end smeared with glue over the entire area without folds or wrinkles. When the gluing process is completed, one end of the rubber tube will be inside the other. The place of gluing is pressed by hand.

After gluing the first joint, the mandrels are removed and the second joint is glued in the same way, connecting the chamber into a closed ring. After that, the mandrels are easily removed from the chamber due to the cut of the wall.

If the puncture hole is large and several threads of the tire thread are damaged, the hole in the latter must be sealed. The patch in this case is made of rubberized fabric, which is available in the bike kit. On the damaged area on the inside of the tire, the surface is cleaned with sandpaper, several layers of rubber glue are applied at intervals of 15-20 minutes to dry. After that, a patch smeared with glue and dried is also applied to the place of damage and it is well rolled to the tire.

In case of significant cuts in the tire, it is best to repair it by hot vulcanizing in the workshop that performs this work.

Repairing a damaged racing single tube is somewhat different from repairing a road tire and requires more care and attention. It is not recommended to submerge the racing single tube in water to find the puncture site. The puncture is determined by ear or, if this is not possible, soap foam is prepared, as for shaving (only not hot), and applied with a brush to the sides of the single-tube along the entire circumference; Foam will begin to bubble at the puncture site. The puncture site is noticed, and the foam is removed from the sides of the tire with a dry cloth.

The single tube is emptied of air and removed from the rim. To remove the chamber from the tire, you need to carefully tear off the keeper tape glued to it from the tire frame, which closes the butt seam. The tape is torn off the tire in a fairly significant area. Being careful not to cut through the chambers, cut the threads of the butt weld; the incision is made so long that you can freely remove the camera. After that, the edge of the safety tape is undercut so that it is possible to freely remove the camera and repair it.

After that, the edge of the safety tape is undercut so that it is possible to freely remove the camera and repair it.

Damaged tire carcass fabric must be sealed during a puncture, otherwise the thin wall of the chamber, drawn into the puncture hole in contact with the road surface on which the wheel moves, will be pinched or rubbed. The puncture hole in the tire frame is sealed with a piece of bicycle thread from an old single tube; you can also seal the hole with a dense canvas from a parachute or balloon.

The method of sealing a racing tire tube is the same as the described method of sticking a road tube, but since the thickness of the walls of the tube and the patch is only about 0.3 mm, and sometimes less, they must be cleaned with fine-grained sandpaper.

After the repair of the tire and the inner tube, the latter is inserted into the tire and sutured end-to-end with a cross stitch. The crosslinking process is shown in Fig. 69. Then the seam is sealed with a keeper tape.

If it is necessary to reinforce the tread, a rubber strip 22–24 mm wide and equal to the wheel circumference, cut from a piece of rubber or from a road tire chamber, is glued to its surface. The strip, before sticking, is cleaned on one side, and then coated several times with rubber glue.

The protector is also cleaned and lubricated with glue. After the last applied layer of rubber adhesive has dried, the rubber strip is applied. When sticking, the strip cannot be pulled, otherwise the single-tube removed from the rim will sharply shorten in length and the tire frame will be covered with many folds, which adversely affects its safety.

Fig. 69. Stitching a single-tube tire

Sooner or later, every cyclist has such an unpleasant situation as a bicycle inner tube puncture. Finding a flat tire at home is one thing (although it also requires some knowledge of camera repair), but what if you blew it during a multi-kilometer ride, for example, somewhere in a field? How to determine the puncture site in such a situation, correctly change and seal the bicycle chamber, what kind of glue and patches are best suited for this purpose. In addition, in this article we will consider some of the nuances of repair and proper operation of bicycle chambers, for example, we will talk about what pressure they should have and much more. 9Ol000 Related video

In addition, in this article we will consider some of the nuances of repair and proper operation of bicycle chambers, for example, we will talk about what pressure they should have and much more. 9Ol000 Related video

During long trips, it is advisable to carry not only a bicycle tool, but also a spare tube, with which you can quickly replace the failed one and go further. After all, this is much faster than waiting for the glue to dry on a freshly sealed one. Therefore, in this section we will consider such a question as how to remove a bicycle tire and replace the camera when it is punctured.

If there is nothing at hand, then remember this position, relying on the side inscriptions. After that, the wheel should remain only on this side. This is necessary so that after we take out the camera and find a puncture on it, we can, by attaching it to the tire, find the place where the foreign object pierced the latter. In most cases, the plant's nail or needle remains in the bike tire, and if left unremoved, it will pierce the new tube as soon as it is replaced.

If there is nothing at hand, then remember this position, relying on the side inscriptions. After that, the wheel should remain only on this side. This is necessary so that after we take out the camera and find a puncture on it, we can, by attaching it to the tire, find the place where the foreign object pierced the latter. In most cases, the plant's nail or needle remains in the bike tire, and if left unremoved, it will pierce the new tube as soon as it is replaced. Be careful not to get a tube between the mount and the rim. This may lead to its rupture. If you do not have a magazine spatula, then you can use any non-sharp, preferably plastic object of a similar shape. It is not necessary to use wooden products for these purposes (they may be with burrs) or metal products that damage the paintwork of the bicycle rim. Sharp objects (screwdrivers, knives, etc.) are strictly not recommended for use. They can damage both the tube and the tire.

It is not necessary to use wooden products for these purposes (they may be with burrs) or metal products that damage the paintwork of the bicycle rim. Sharp objects (screwdrivers, knives, etc.) are strictly not recommended for use. They can damage both the tube and the tire.

It is important not to turn it over to the other side until we find the puncture site and find it on the tire (by attaching a tube to it).

After we remove it, we leave the tire in the same position as it stood on the rim (to search for a foreign object stuck in it).

After we remove it, we leave the tire in the same position as it stood on the rim (to search for a foreign object stuck in it).  Next, we insert a new chamber inside, pulling the nipple through the corresponding hole on the rim (for ease of installation, the bicycle chamber can be pumped up a little), and put on the second side. We inflate the wheel with a pump and screw on the cap.

Next, we insert a new chamber inside, pulling the nipple through the corresponding hole on the rim (for ease of installation, the bicycle chamber can be pumped up a little), and put on the second side. We inflate the wheel with a pump and screw on the cap. The punctured chamber should then be repaired, for example after you have returned home from a bike ride or during a break.

At first glance, a very simple procedure for identifying a puncture site can become much more complicated depending on where you find a flat tire (at home or during a trip). To simplify the search procedure, it should be taken into account that in 90% of cases it is located on the so-called "contact spot" of the wheel with the road, usually no higher than 2/3 of the chamber height. An exception may be damage from the rim (if the rim tape failed on the latter) or the iron threads of the tire cord that came out. Therefore, we will consider several options for how to find a hole in the bicycle chamber through which air is bled.

Not all adhesives and patches are suitable for repairing a punctured bicycle wheel. Therefore, it is worth dwelling in more detail on the topic of what is possible and what should not be sealed with a bike camera. There are several options, which we will discuss below.

Some riders underestimate the power of the Chinese industry and look down on their belts. I can’t talk about everything (I’m sure some of them are really terrible), but for the last 4 years I’ve been using exclusively Chinese Red Sun patches (although this may not be a company, but the name of a repair kit). They are quite common. For several years of use, none of the patches flew off and began to let air through. And the cost of this product is lower than that of famous brands. The disadvantages include that the set contains only glue and patches, and what is most offensive, there are disproportionately more patches than glue. Well, these are already trifles. In general, I advise everyone.

Some riders underestimate the power of the Chinese industry and look down on their belts. I can’t talk about everything (I’m sure some of them are really terrible), but for the last 4 years I’ve been using exclusively Chinese Red Sun patches (although this may not be a company, but the name of a repair kit). They are quite common. For several years of use, none of the patches flew off and began to let air through. And the cost of this product is lower than that of famous brands. The disadvantages include that the set contains only glue and patches, and what is most offensive, there are disproportionately more patches than glue. Well, these are already trifles. In general, I advise everyone.  It says so, "at your own peril and risk." When using homemade patches, you can not use glue, which, when solidified, can burst at the bends.

It says so, "at your own peril and risk." When using homemade patches, you can not use glue, which, when solidified, can burst at the bends. After we have found and marked the place of the bicycle inner tube puncture, it is necessary to start its repair, namely, to seal this hole. To do this, you must perform the following operations.

The sanding area should be 1 centimeter larger than the size of the bike patch in diameter. After this procedure, we try not to touch this place with our hands or other objects.

The sanding area should be 1 centimeter larger than the size of the bike patch in diameter. After this procedure, we try not to touch this place with our hands or other objects.

If, after you have sealed a puncture on the bike tube, it still deflates over time, you should check: To do this, the place with the patch should be lowered into the water and make sure there are no air bubbles. If they are, then you will have to tear off the old and glue a new patch.

If such a problem is found, the tire should be replaced as soon as possible. A temporary solution is to pull out the protruding cord wire and seal this place with a patch for the camera. But I repeat that in this case, a tire replacement is required, because. this will be repeated regularly.

If such a problem is found, the tire should be replaced as soon as possible. A temporary solution is to pull out the protruding cord wire and seal this place with a patch for the camera. But I repeat that in this case, a tire replacement is required, because. this will be repeated regularly. If the tube is damaged at the base of the nipple (for example, it is rubbed by the rim), it is best to replace it immediately. As a rule, such defects cannot be repaired.

To reduce the chance of unexpected tire and tube damage while riding, follow a few simple rules.

It looks like this. If the pressure is too low, this greatly increases the risk of puncture. It is worth remembering that when driving in winter or in the autumn-spring period, the temperature outside is lower than in the apartment. Therefore, on cold days, the chamber should be inflated a little more (because as the temperature of the air in the closed volume decreases, its pressure decreases). Therefore, if you pump up to 3 bar in summer, then in winter you can increase the pressure by about 1 bar (but not higher than the maximum allowable).

It looks like this. If the pressure is too low, this greatly increases the risk of puncture. It is worth remembering that when driving in winter or in the autumn-spring period, the temperature outside is lower than in the apartment. Therefore, on cold days, the chamber should be inflated a little more (because as the temperature of the air in the closed volume decreases, its pressure decreases). Therefore, if you pump up to 3 bar in summer, then in winter you can increase the pressure by about 1 bar (but not higher than the maximum allowable). There are two more devices on the bike parts market that are designed to make life easier (at least they position themselves that way) when riding a bike. This is an anti-puncture tape and sealant, which is poured in a small amount into the chamber and is designed to “tighten” punctures while driving.

This is an anti-puncture tape and sealant, which is poured in a small amount into the chamber and is designed to “tighten” punctures while driving.

Anti-puncture tape is a strip of soft, rubberized plastic or, in more expensive products, Kevlar, that can be glued or simply inserted between the tire and the bicycle tube to protect against punctures. But there are pitfalls here. Cheap anti-puncture, firstly, does not always protect against punctures, and secondly, it can fall apart inside the tire and rub the chamber into dust with its fragments, thereby dooming the latter to ejection. Plus, it's extra weight. In general, after sitting on the forums, I agreed that they are more blamed than praised.

As far as the sealant is concerned, things are not so good either. As a temporary solution, when you don’t want to bother with replacing the camera, you can, of course, use it. But the sealant does not seal the puncture completely, but only reduces air leakage. Plus, there were complaints after use, when they wanted to stick a patch on the puncture site.