(Update! The crocodile has apparently been freed, according to the BBC and other news outlets. A local man named Tili, who described himself as a self-taught reptile rescuer, spent weeks tracking and trying to trap the tire’d croc before finally succeeding. Recently released video shows him using a small saw to cut through the tire.)

For years, people in the Indonesian province of Central Sulawesi have been able to easily identify a specific crocodile stalking the Palu River. In some respects, this one looks like many others: It’s mosaicked with mud-colored scales, boasts a long-and-strong tail, and brandishes powerful, cone-shaped teeth. But there’s one foolproof way to distinguish this croc from its kin: It wears a rubber tire like a collar.

The crocodile has been trapped in this tire for around five years. In the 21st century, it’s not especially unusual for an animal to get ensnared in human trash, with sometimes lethal consequences: In a study published last year in the Journal of Hazardous Materials, researchers estimated that roughly 570,000 strawberry hermit crabs—which look like a fistful of red gummy worms stuffed into a piece of conchiglie pasta—become fatally caught in plastic debris each year on Henderson Island and the Cocos (Keeling) Islands, freckles of land in the South Pacific and Indian Ocean, respectively. Researchers have also recently tracked how fish, birds, and other creatures end up entwined in plastic gloves, face masks, and other pieces of PPE cast off during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Aquatic environments are the number one place where this sort of thing happens,” says Sara Ruane, a herpetologist at the Field Museum in Chicago. Sure, a balloon could blow into a tree, Ruane adds, but crocs and other swimming reptiles often travel into garbage-studded areas face-first, with nothing to stop a tire or a set of six-pack rings from encircling them.

It’s sadly common for animals to encounter plastic pollution in watery ecosystems. Ivan Radic/CC by 2.0But five years is an awfully long time to be trapped—many creatures trapped in or bogged down by trash would be long dead by that point. So how has this animal survived, and what is the tire doing to it?

If the animal was ringed by the tire when it was young, when crocodiles grow most rapidly, the rubber loop may have permanently constricted its growth, and led to indentations, discoloration, or bent scales. But, according to Kent Vliet, a biologist at the University of Florida who specializes in alligators and crocodiles, as long as the croc can continue to eat, it should hang in there. Based on the animal’s appearance, Vliet doesn’t think it’s going hungry. “It’s not the fattest crocodile I’ve ever seen,” he says, “but it’s got a good body weight on it.”

But, according to Kent Vliet, a biologist at the University of Florida who specializes in alligators and crocodiles, as long as the croc can continue to eat, it should hang in there. Based on the animal’s appearance, Vliet doesn’t think it’s going hungry. “It’s not the fattest crocodile I’ve ever seen,” he says, “but it’s got a good body weight on it.”

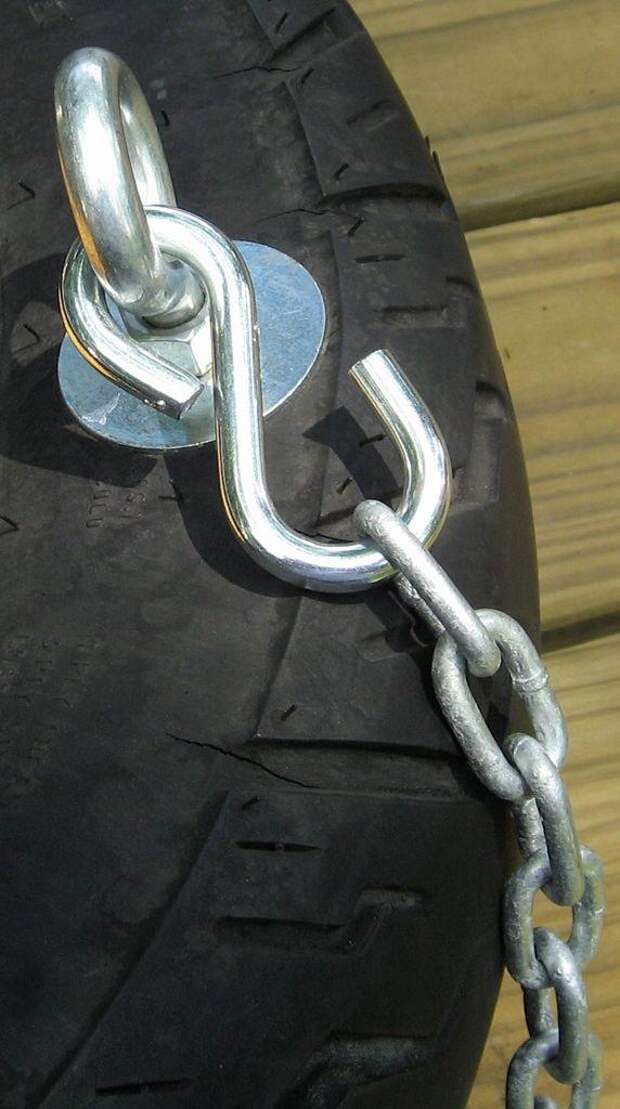

Judging from photos, the tire is encircling the reptile’s throat, which includes the larynx, esophagus, and trachea. While the animal is probably able to breathe and vocalize just fine, the tire could constrain the size of prey it can consume, says Vliet, who suspects this crocodile is either a saltwater crocodile (

Crocodylus porosus), or a hybrid of a saltwater croc and the endangered Crocodylus siamensis. In addition to smaller prey (such as fish and water rats or rabbit-sized mammals), saltwater crocodiles go after some pretty enormous meals—including, occasionally, humans. In Australia, they are known to feast on water buffalo, kangaroos, and wallabies. The crocs don’t always go for these bigger challenges, but “if they can, they will,” Vliet says. They manage it by distending their throat, which stretches from their eyes down to their front legs. “That would be restricted with that tire,” Vliet says. “I’m imagining that would make it impossible to take a large prey item.”

The crocs don’t always go for these bigger challenges, but “if they can, they will,” Vliet says. They manage it by distending their throat, which stretches from their eyes down to their front legs. “That would be restricted with that tire,” Vliet says. “I’m imagining that would make it impossible to take a large prey item.”

The tire could also make it harder for the croc to hunt. The rubber ring is bulky and obvious, two qualities that make it hard to be stealthy. “These animals are ambush predators, which is another way of saying they hang out at water’s edge and pretend to be a log until something comes along,” says Stephanie Drumheller-Horton, a paleontologist and adjunct assistant professor at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, who studies crocodilians. As the croc swims near the surface, the tire probably sets the water rippling, tipping off prey and making it “harder for that animal to go about its normal business,” Vliet says.

The tire could impede the croc’s ability to be stealthy. Getty/NurPhoto/Contributor

Getty/NurPhoto/ContributorThe impact of the conspicuous tire might also make this individual vulnerable to his own species, especially if the animal occupies a low rung of the local social ladder. This species is notoriously territorial, and “dominant males are pretty hard on subordinate males,” Vliet says. The tire ringing the snout creates a striking silhouette, which could “increase the ire” of dominant males, he adds, and provoke aggression. The fossil record is stuffed with evidence of the animals fighting each other, Drumheller-Horton says, and “before we came along, usually the biggest threat to a crocodile was another crocodile.”

In the wild, some crocs achieve septuagenarian status—saltwater crocodiles can live up to 75 years—and Vliet doesn’t think the tire will necessarily shorten the creature’s lifespan, unless it catches on something. That has been a familiar scenario since biologists began collaring the animals with radio trackers decades ago. When scientists strap cameras or radios to alligators or crocodiles, the reptiles “do a pretty good job of getting it caught” on vines or tree roots jutting from the water, Vliet says. Biologists now often opt for hydrodynamic tracker designs—far lower-profile than an old tire. Getting snagged on land or in the water could have dire consequences if the croc can’t free itself.

Biologists now often opt for hydrodynamic tracker designs—far lower-profile than an old tire. Getting snagged on land or in the water could have dire consequences if the croc can’t free itself.

Vliet and Drumheller-Horton agree that the best way forward is to enlist trained professionals to capture the croc and remove the tire, maybe by cutting it off. However, previous attempts to capture the croc and remove the tire—including a scheme to bribe it with chicken—have been unsuccessful. “The problem with crocs is, when you start trying to catch them, they get wary—and any time you look at them sideways, they disappear on you,” Vliet says.

Meanwhile, this poor crocodile has become a curiosity, and a living reminder that human actions such as indiscriminate dumping have far-reaching consequences. Trash cans, drains, and recycling bins aren’t chutes through which our garbage vanishes. It can still have an afterlife. “Our trash goes somewhere,” Drumheller-Horton says, “and it can end up affecting animals in unexpected and negative ways. ” This crocodile is dragging the legacy of our pollution around with it. And Ruane notes that, unfortunately, many other animals have it far worse. When we see a trash-trapped creature that’s alive, we’re “probably seeing the exceptions,” Ruane says. “You’re not seeing the ones that didn’t make it, or weren’t able to grow around the problem.”

” This crocodile is dragging the legacy of our pollution around with it. And Ruane notes that, unfortunately, many other animals have it far worse. When we see a trash-trapped creature that’s alive, we’re “probably seeing the exceptions,” Ruane says. “You’re not seeing the ones that didn’t make it, or weren’t able to grow around the problem.”

This story originally ran in 2021; it has been updated for 2022.

Read next

Syracuse got one for salt potatoes—could your hometown be next?

plasticpollutionreptilestrashbiologyecologyscience

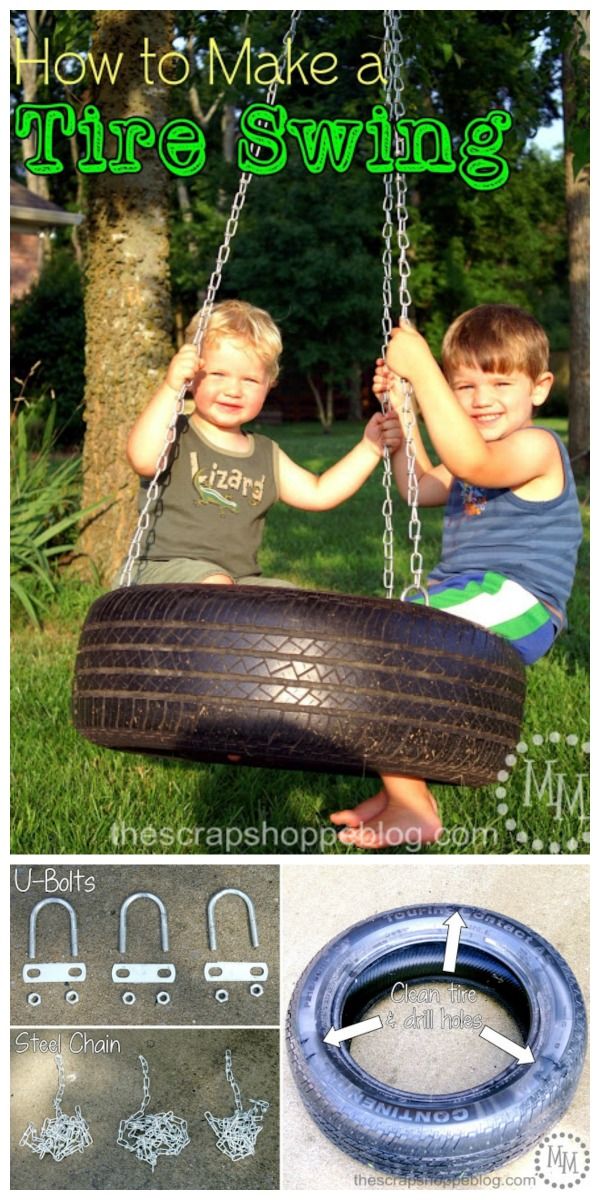

At this year’s Kaleido Family Arts Festival, you might find an alligator lurking along Alberta Avenue. Moulded out of old tires, the treaded reptile will be one of a handful of community art projects created from reused and recycled materials.

The gator’s sculptor, Arts on the Ave executive assistant Elena Petzold, will be working with some of the 50 odd tires Downtown Auto donated as material for several temporary installations set to appear along 118 Avenue between Sept. 15 and 17.

15 and 17.

A fine arts graduate from the University of Lethbridge, Petzold is a visual artist with experience in woodworking, bronze casting, and welding metal installations. She has never worked with tires before, but isn’t shying away from the challenge. In the meantime, she’s been studying the new medium and learning how to make it pliable.

Elena Petzold will be sculpting an alligator out of tires for the Kaleido Family Arts Festival running Sept. 15 to 17. | Hamdi Issawi“Rubber doesn’t work the same as metal or wood, so the main thing with this material is just cutting. Tires have wire thread through them, so you have to cut out all the wire before using the tire, otherwise it won’t bend,” Petzold explained. “With art, you’re always taking a bit of a risk, which is exciting. You have to adapt along the way. ”

”

The idea for the sculpture came from Christy Morin, Kaleido’s founder and artistic director. After visiting a community arts garden in London, England, Morin saw how tires could be used to sculpt objects like alligators, chameleons, totem poles, and even people. The experience inspired her to commission similar exhibits for the festival.

On Sept. 9 and 10, artists are invited to help paint and assemble tire sculptures like this totem pole found at the Nomadic Community Garden in England. | Christy MorinMorin isn’t revealing the location of the sculptures. “You just have to look for them,” Morin said playfully. “So you might be walking around the corner, and there’s an alligator, or a tea cup. It’s all about making the Ave home.”

But festivalgoers can do more than just appreciate these sculptures—they’re also invited to lend a creative hand.

On Sept. 9 and 10, Downtown Auto is hosting workshops for people to help build and paint tire installations for the festival.

“We’re looking for volunteers who have a bent towards street art,” Morin said. “If you’re used to using a spray can and can fill in a space, that would be great.”

Volunteers should expect to lift and move heavy tires in the process.

“It’s hard work,” Morin added. “You’re going to sweat.”

Nevertheless, Lauren Bohnet, the festival’s installation coordinator, hopes community members take advantage of a unique opportunity to participate.

“The more the merrier,” Bohnet said. “Once it’s all done, it will be cool for people who helped to see their art around the Ave.”

Workshop volunteers may even get a behind-the-scenes glimpse of Petzold wrestling rubber to bring her own sculpture to life.

“We’re taking something that’s existing and making it come alive,” Petzold said. “That’s part of what Kaleido does: we’re repurposing it for art.”

Volunteers interested in attending the workshops can contact Lauren Bohnet at [email protected]

Featured Image: Visitors at this year’s Kaleido can expect to find interactive community art created from repurposed material. | Epic Photography

| Epic Photography

Crocodile from a tire is a frequent resident of the plots. No wonder: the texture of the material for such crafts for the garden is ideal. In fact, convex rhombuses, squares are almost crocodile skin.

Especially such crocodiles like to “settle” near ornamental ponds (or even in them).

Almost always crafts from tires - crocodiles are painted green. Logically: crocodiles are green. But not all. For example, alligators are dark gray, brown or even black. Very serious animals (carnivorous reptiles), impressive.

So if you get a tire from a big vehicle, don't "translate" it to crocodiles - make an alligator. But, in principle, large crafts from the garden in the form of alligators are quite simple to make by connecting several tires. The easiest way is to cut the tire with a saw (with an electric saw, the tire, in general, is cut like butter), and make holes with an electric drill with a large drill. Fasten with tighter wire.

Fasten with tighter wire.

Insert pieces of metal rods (reinforcement) for the legs to hold the body. And in no case do not paint - immediately the status of the alligator crafts for the garden will disappear, and you will face an ordinary crocodile from a tire.

Tire alligators look very natural in the grass, among stones, under trees (by the way, real alligators dig their holes under trees, among the roots).

In nature, adult alligators have different sizes - depending on the species. So, male Chinese alligators have a length of up to 2.2 m, females - 1.4-1.6 m. Their American "relatives" are much larger: males reach a length of 4-4.5 m, females - 2.5-3 m. Be guided by these indicators when making such original crafts for the garden. You can make a whole family - it will look interesting.

MORE FOR THE GARDEN:

Ideas for the garden: a very interesting lion from bottles

Crafts from plastic bottles: Tree of happiness in the garden

Adorable pied hen and cockerel made of plastic bottles unique: 9002 9002 9002 palm tree

Tire Dolphin

Flowerbed Swan - Easy Creation

Plastic Bottle Crafts: Amazing TreeFancy Plastic Bottle Flower Beds

Plastic Bottle Flowers with Hard Petals

Garden Crafts: Fantastic Chickens!

Garden figures: Funny boar

Golden tire fountain

Garden crafts: super beeGarden decorations from an old trunk

Ornamental tree in the garden

Plastic bottle palm tree: plastic bottle crafts

flower beds

Palm tree from plastic bottles: with BANANA!

Golden snail tire