Clinical Pathways in Emergency Medicine. 2016 Feb 22 : 329–345.

Published online 2016 Feb 22. doi: 10.1007/978-81-322-2710-6_26

PMCID: PMC7121692

Guest Editor (s): Suresh S David

PushpagiriMedical College Hospital, Kerala, India

Suresh S David, Email: [email protected].

, MBBS, MD (EM), MCEM, FACEE

Author information Copyright and License information Disclaimer

Wide range of pathologies may present with abdominal pain.

Key to reach proper diagnosis is adequate history and physical examination along with laboratory tests and imaging.

Disposition of patients with abdominal pain is as difficult as its diagnosis.

Low threshold should be kept for high-risk patients.

Life-threatening diseases should not be missed in emergency.

Keywords: Herpes Zoster, Acute Appendicitis, Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm, Ectopic Pregnancy, Mesenteric Ischaemia

Wide range of pathologies may present with abdominal pain.

Key to reach proper diagnosis is adequate history and physical examination along with laboratory tests and imaging.

Disposition of patients with abdominal pain is as difficult as its diagnosis.

Low threshold should be kept for high-risk patients.

Life-threatening diseases should not be missed in emergency.

Abdominal pain is one of the most common reasons for emergency department visits. Incidence is around 10–12 % globally. Demographic factors like age, gender, ethnicity and family history affect its presentation.

It is paramount for emergency physicians to have methodical approach in history, physical examination, investigation and treatment. Clinical suspicion of life-threatening diseases in high-risk patients is utmost important.

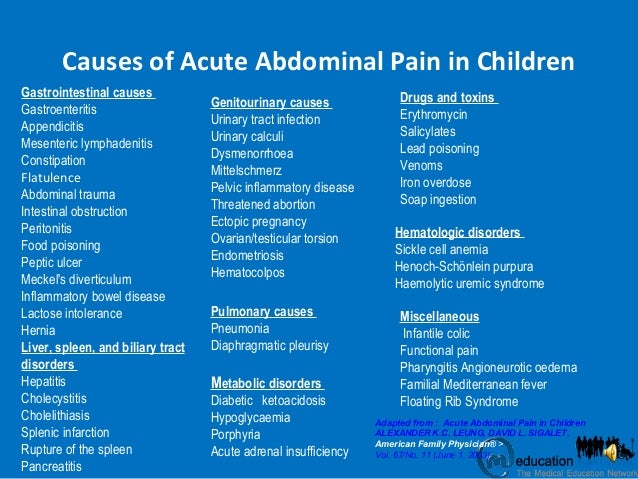

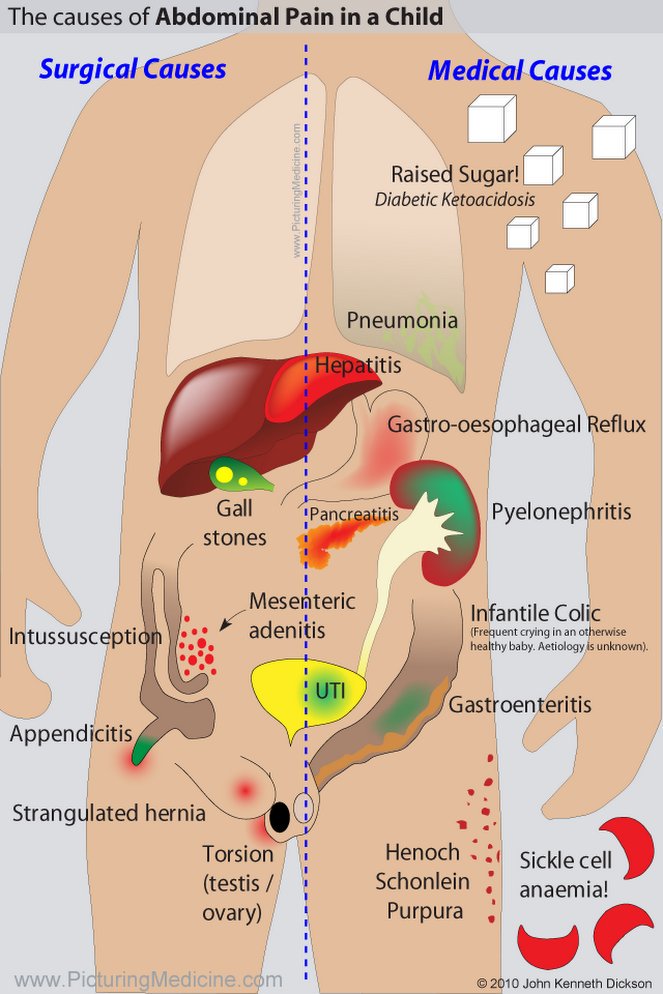

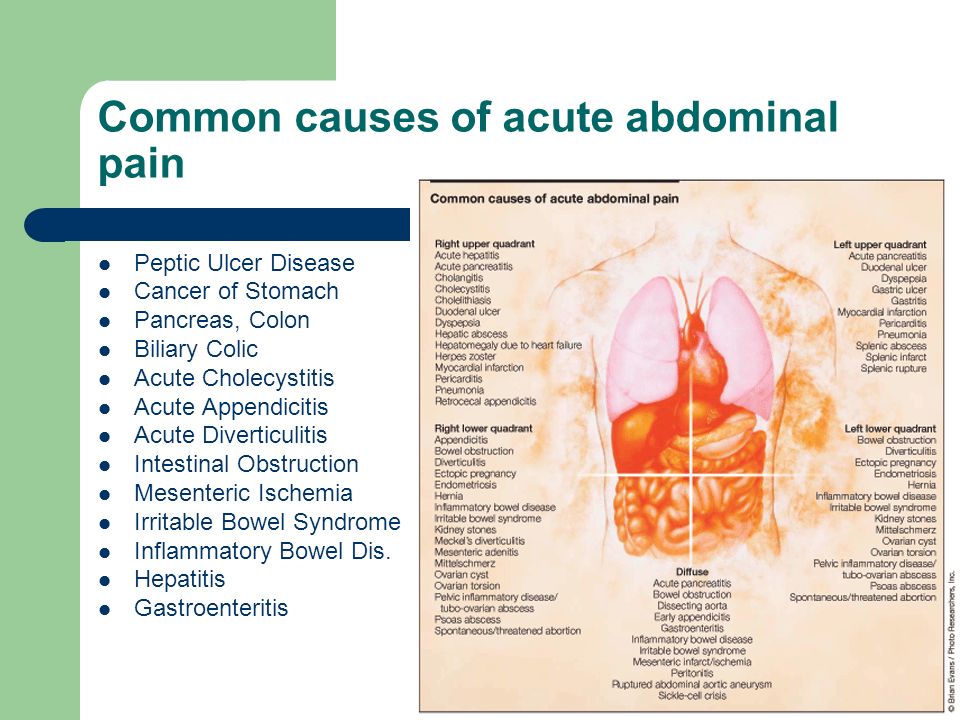

Many intra-abdominal and extra-abdominal diseases are responsible for abdominal pain.

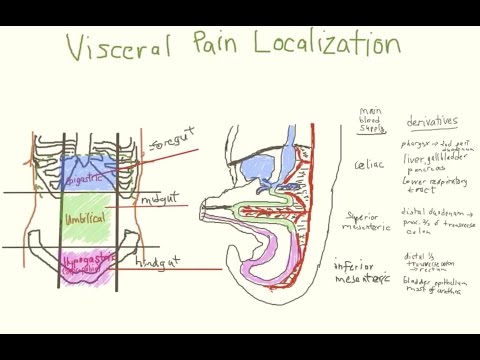

Nature of abdominal pain can be divided into three categories based on neurological pathways:

Somatic (parietal) pain:

It results from irritation of parietal peritoneum caused by inflammation, infection or chemical reaction. It is supplied by myelinated nerve fibres. It is localised and constant. As the disease process evolves and irritates parietal peritoneum, we can elicit tenderness, guarding and rigidity. The patient prefers to lie immobile.

Visceral pain:

It is caused by stretching of walls of hollow viscera, innervated by unmyelinated fibres. It is diffuse and intermittent, dull aching and colicky in nature. Patients keep tossing on the bed. It is felt in the abdominal region which correlates to the somatic segment of embryonic region. Foregut, midgut and hindgut structures (Table ) relate to upper, middle and lower abdomen, respectively. Visceral pain can be perceived away from actual disease process, i.e. pain of acute appendicitis is felt around umbilicus initially as it corresponds to T10 somatic distribution.

Patients keep tossing on the bed. It is felt in the abdominal region which correlates to the somatic segment of embryonic region. Foregut, midgut and hindgut structures (Table ) relate to upper, middle and lower abdomen, respectively. Visceral pain can be perceived away from actual disease process, i.e. pain of acute appendicitis is felt around umbilicus initially as it corresponds to T10 somatic distribution.

Abdominal structures and its origin

| Foregut | Stomach, liver, gall bladder, pancreas, first/second part of duodenum |

| Midgut | Third/forth part of duodenum, jejunum, ileum, appendix, caecum, ascending colon, transverse colon (proximal two thirds) |

| Hindgut | Transverse colon (distal one third), descending colon, sigmoid, rectum, genitourinary organs |

Open in a separate window

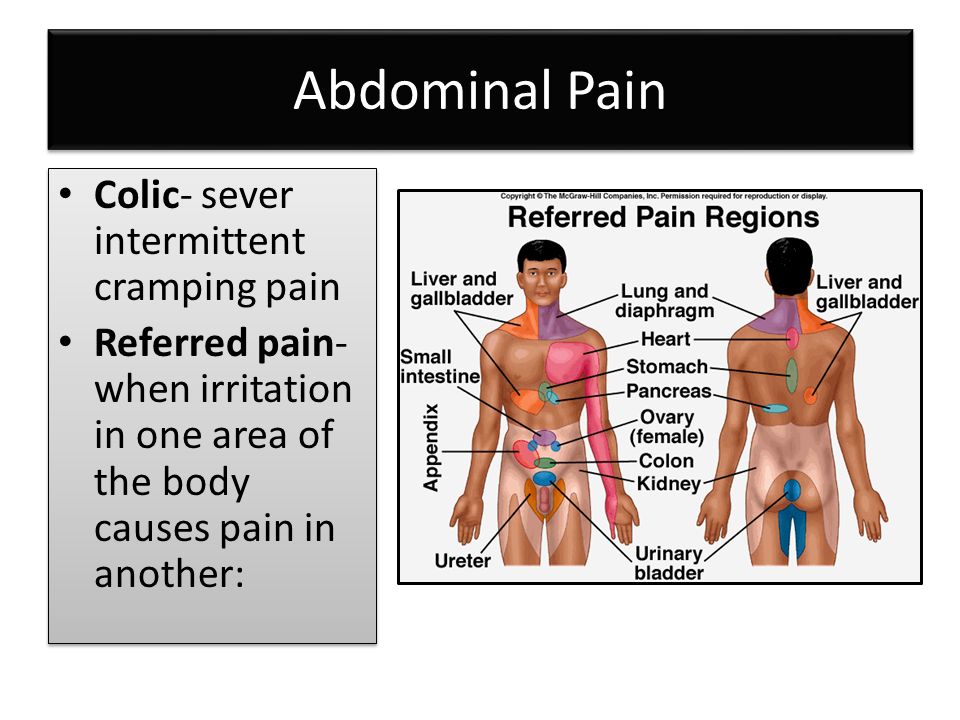

Referred pain:

It is defined as a pain that is felt away from the site of origin. Common anatomical origin or same nerve root innervations are primary reasons for such pain (Fig. ).

Common anatomical origin or same nerve root innervations are primary reasons for such pain (Fig. ).

Open in a separate window

Common locations for referred pain

History:

Age and gender are important history points. Elderly patients with nonspecific complaints may have serious pathology. In females, obstetrics and gynaecological causes should be considered.

Pain can be described as (SCRIPT FADO):

Gastrointestinal complaints (anorexia, nausea, vomiting, altered bowel habits, haematemesis, haematochezia, abdominal distension, back pain), genitourinary problems (urinary complains, foul discharge), thoracic complaints (chest pain, breathlessness, palpitation) and constitutional symptoms (fever, weight loss)

Past history: Regarding previous similar episodes, admissions, investigations and treatment

Pre-existing medical illness: Diabetes, hypertension, heart diseases, liver/renal diseases, HIV, STD and tuberculosis

Medication history: Antibiotics, antiplatelets/anticoagulants, steroids, beta-blockers/calcium channel blockers, NSAIDs, chemotherapeutic agents, etc.

Surgical history: Laparotomy, caesarean sections, etc.

Obstetric history: Last menstrual period, previous pregnancies/deliveries, abortions, ectopic, IVF, IUCDs and other contraceptive measures

Allergies, social history (alcohol/drug addiction), history of last meal and history of trauma

Physical examination:

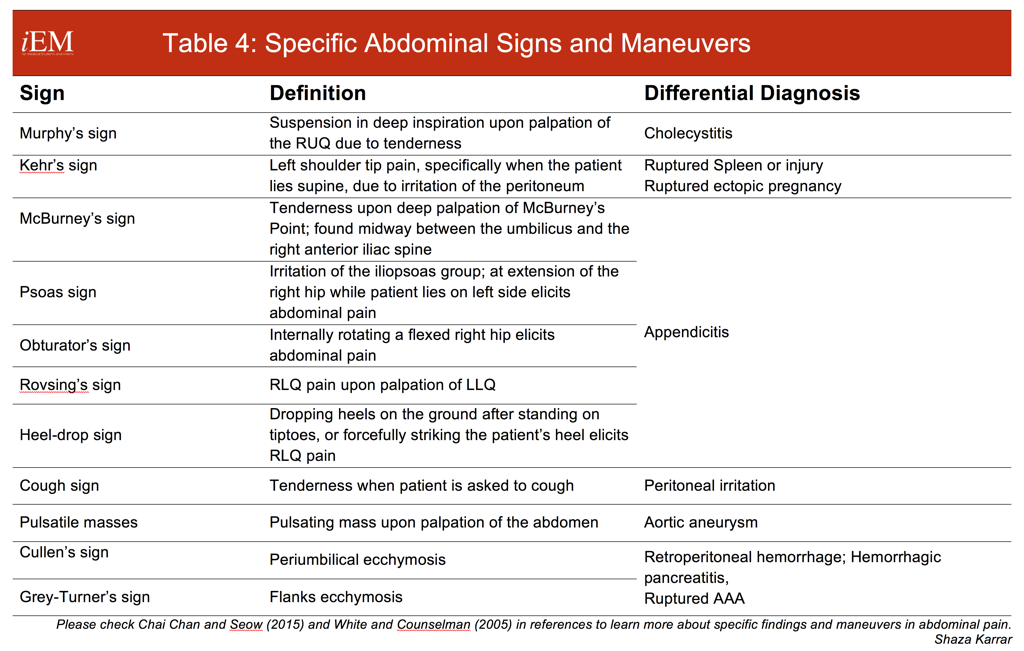

Despite the development of newer imaging modalities, i.e. ultrasound, CT scan and MRI, physical examination holds a key role in patient evaluation. Some specific signs are summarised in Table .

Physical examination correlation

| Respiratory | |

| Restriction | Pleural effusion |

| Crackles | Pneumonia |

| Cardiovascular | |

| Gallop rhythm, arrhythmia | Myocardial infarction |

| Abdomen | |

| Caput medusa | Portal hypertension |

| Bulging flanks | Ascites |

| Visible hernia | Strangulated hernia |

| Tenderness, guarding, rigidity | Peritonitis |

| Shifting dullness | Ascites |

| Absent bowel sounds | Ileus, late sign of bowel obstruction |

| Psoas sign | Retrocaecal appendicitis |

| Obturator sign | Retrocaecal appendicitis, local abscess |

| Rovsing’s sign | Appendicitis |

| Murphy’s sign | Cholecystitis |

| Kehr’s sign | Cholecystitis, perforation |

| Cullen’s sign | Pancreatitis, retroperitoneal bleed |

| Renal angle tenderness | Renal stones |

| Grey Turner sign | Pancreatitis, ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm |

| Rectal | |

| Tenderness | Prostatitis, anal fissure |

| Mass | Anorectal carcinoma, haemorrhoids |

| Empty PR examination | Intestinal obstruction |

| Pelvic | |

| Tenderness | Ectopic pregnancy, PID, ovarian cyst |

| Mass | Ovarian cyst, tumour, abscess |

Open in a separate window

PID pelvic inflammatory disease, PR per rectal

General examination and vital signs: Appearance, temperature, pulse, blood pressure, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, GCS, blood glucose measurement and pain score.

Inspection: With consent, inspect abdominal skin for scars (adhesions), dilated tortuous vein (spider angiomata, caput medusa), skin eruptions (herpes zoster), haemorrhage or signs of trauma (ecchymosis), foreign body and entry/exit wounds. Distension of abdomen (ascites, intestinal obstruction, ileus) and obvious masses (tumour, hernia, pregnancy, distended bladder, aneurysm) should be examined. Hernia orifices and external genitalia should not be forgotten.

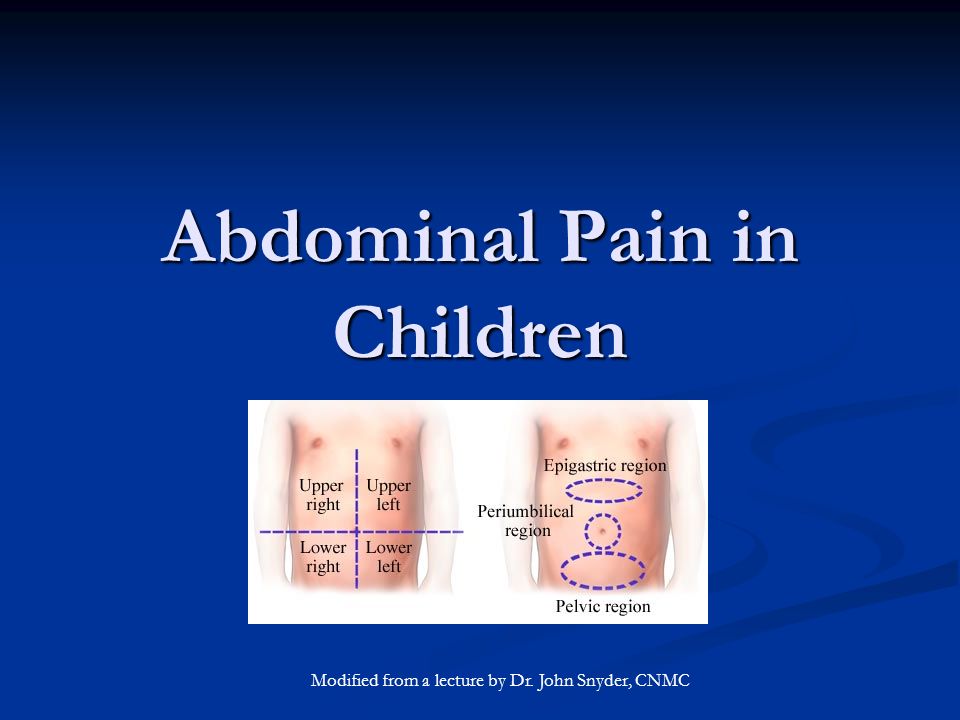

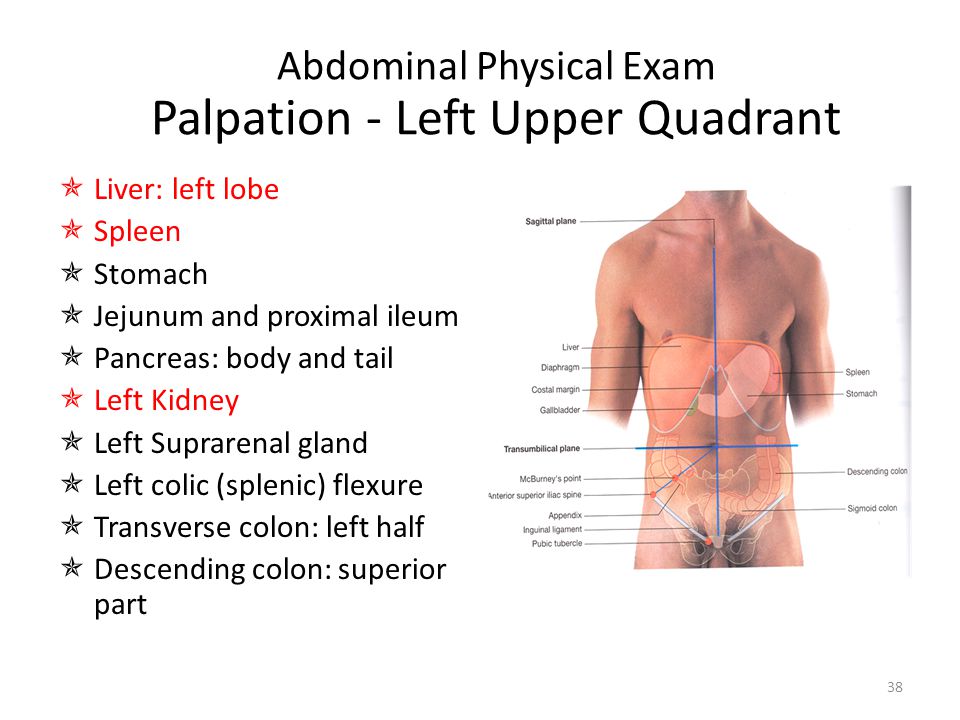

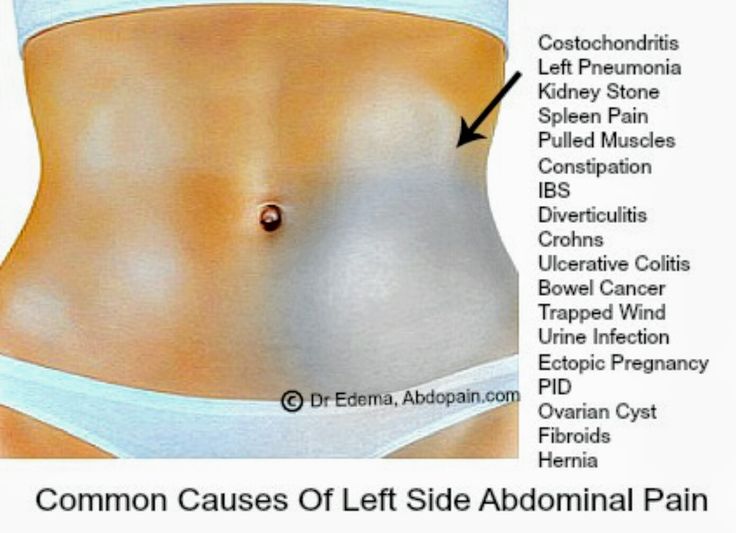

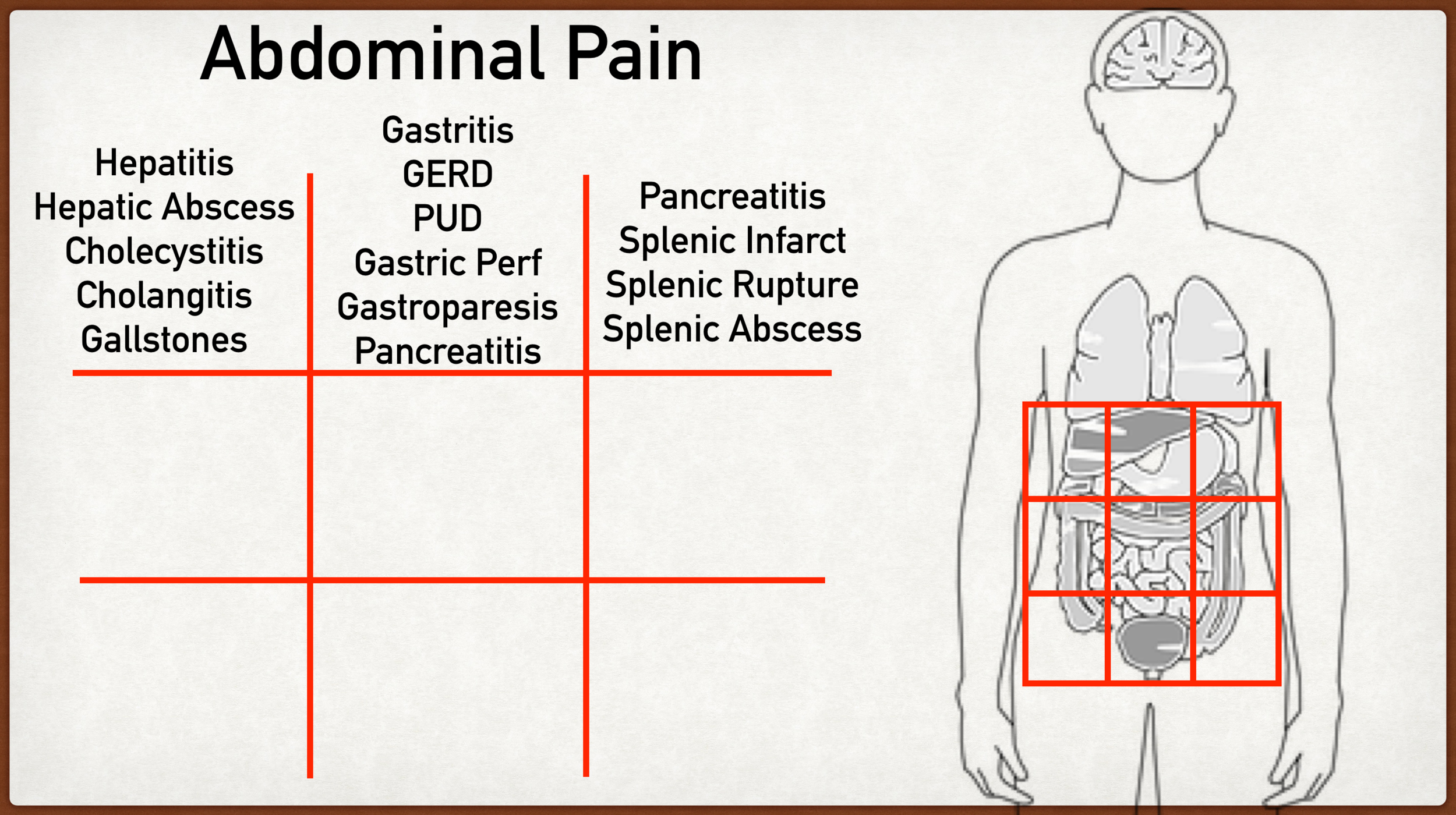

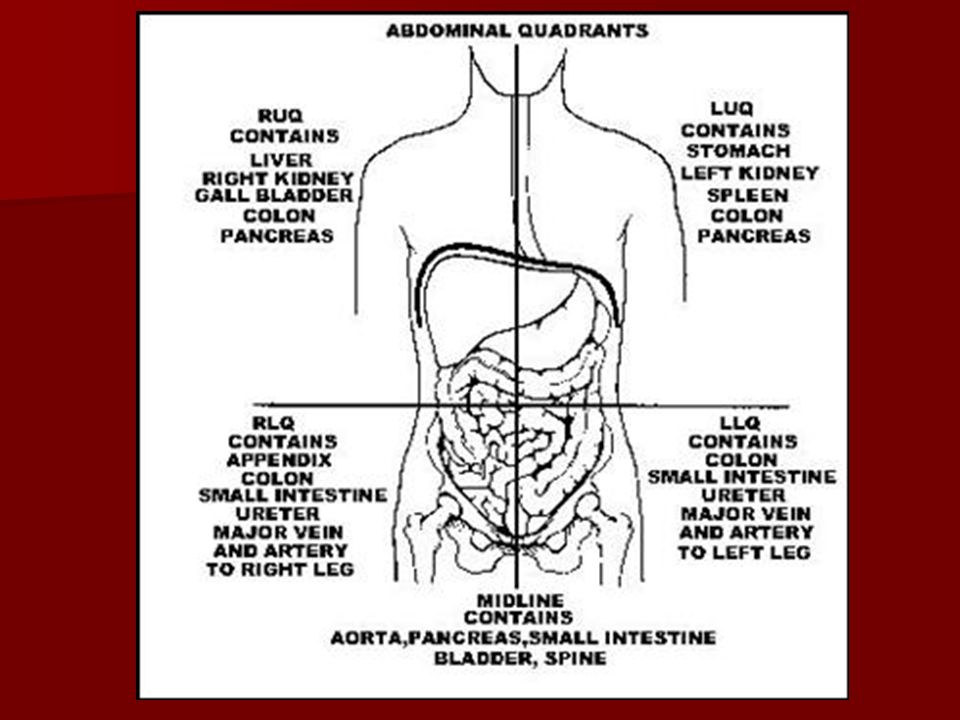

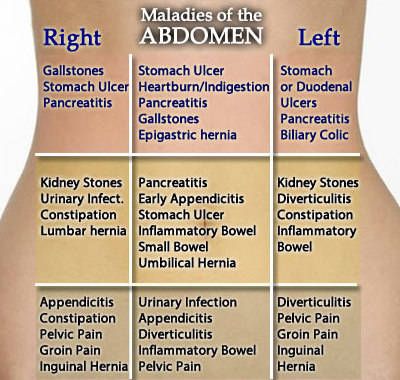

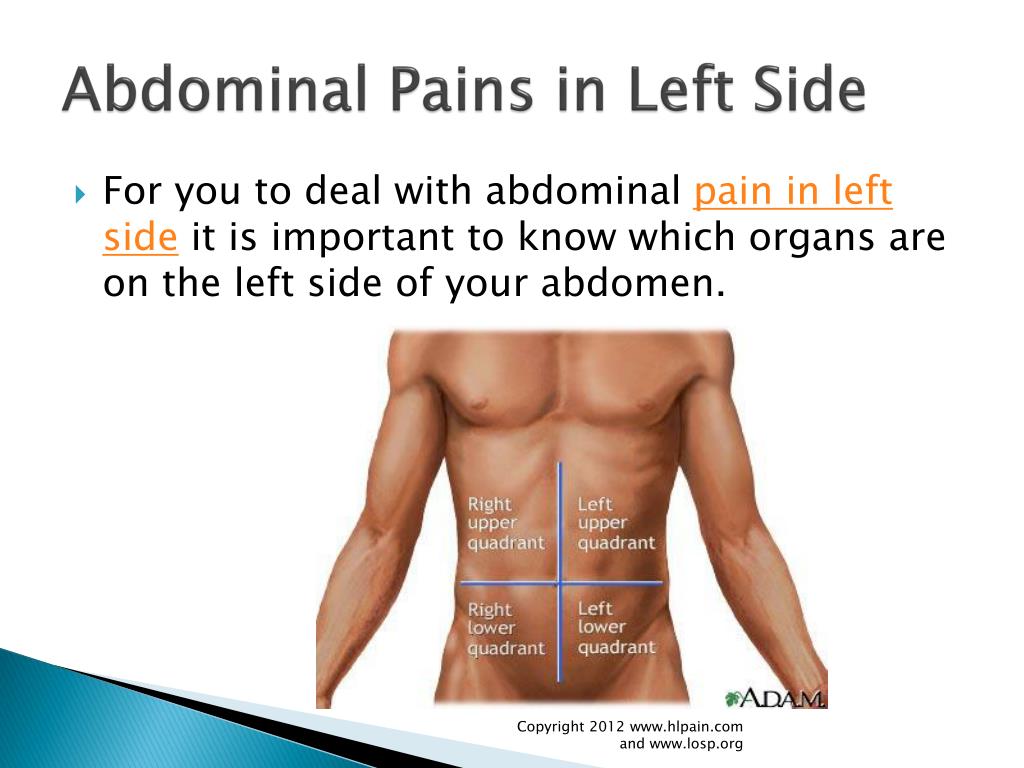

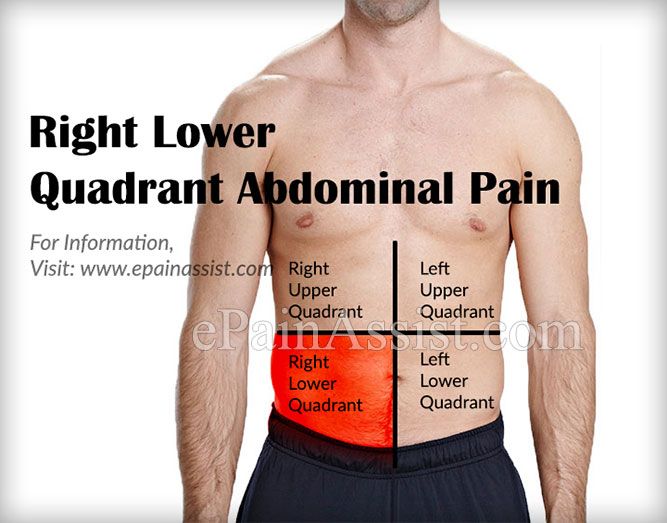

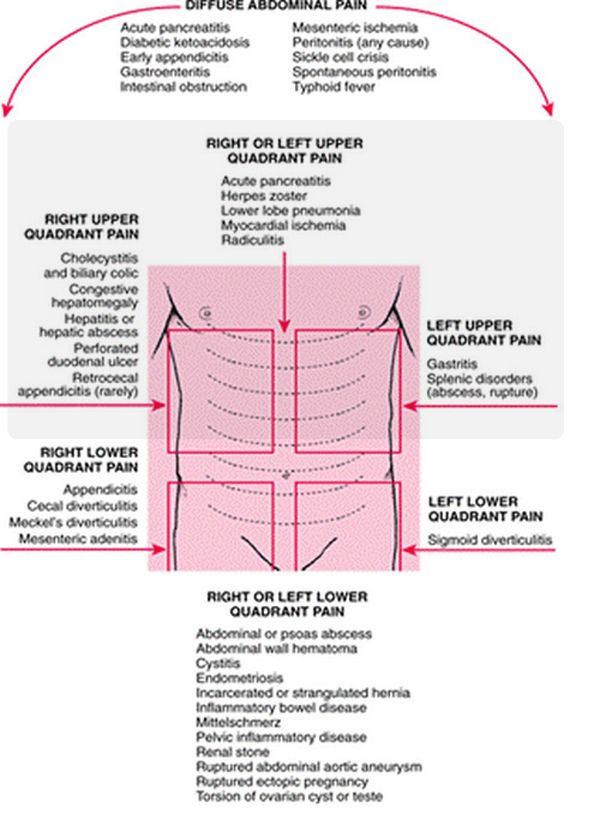

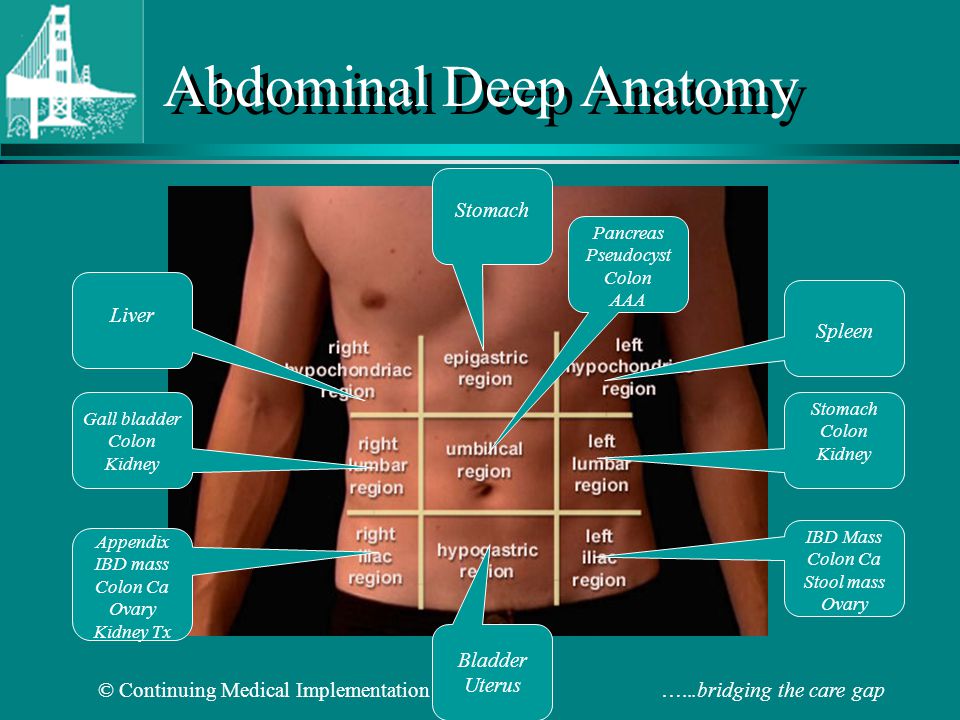

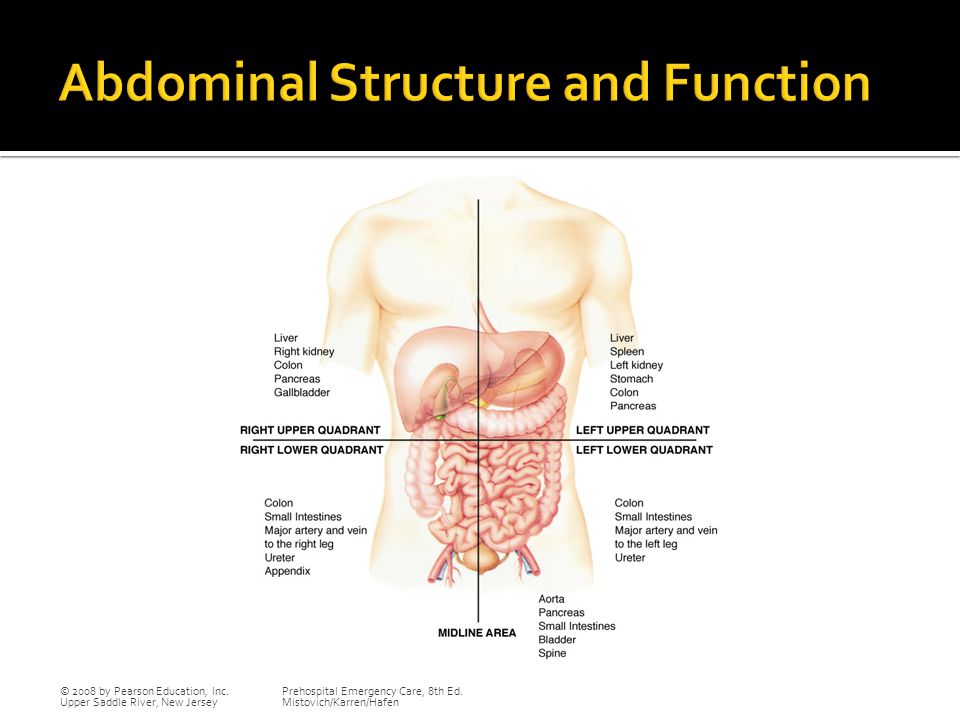

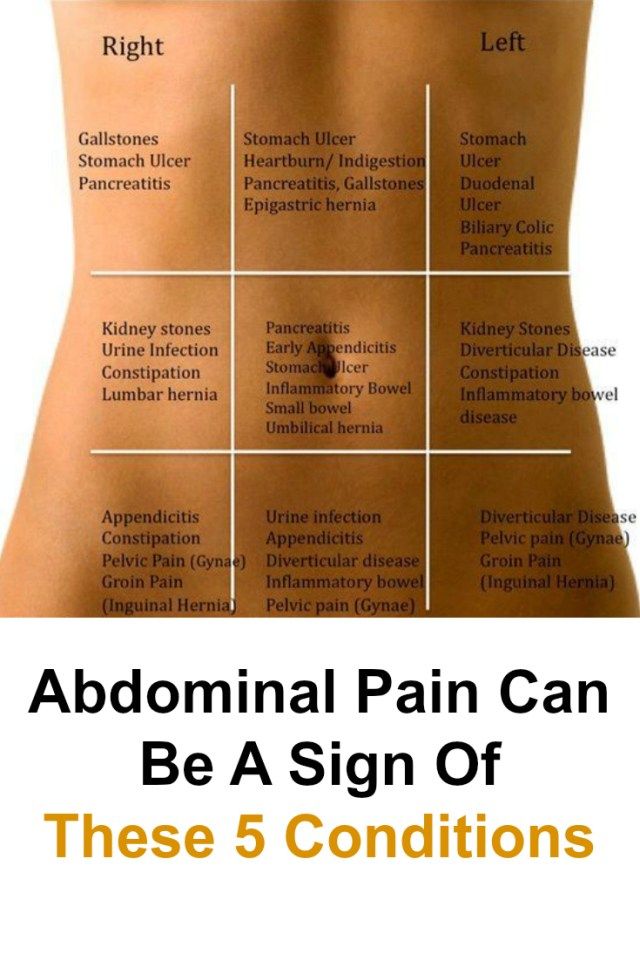

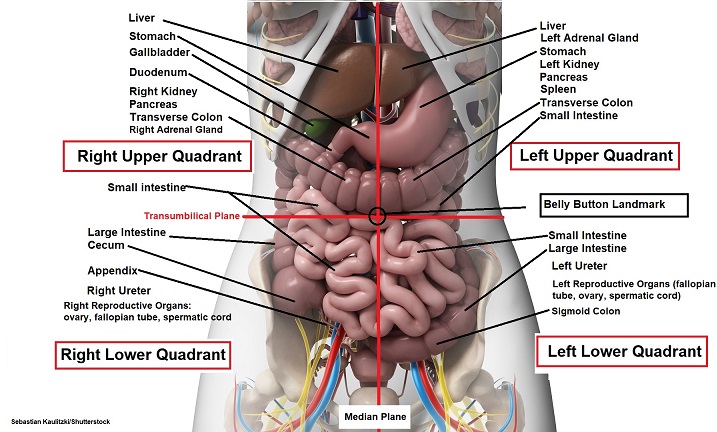

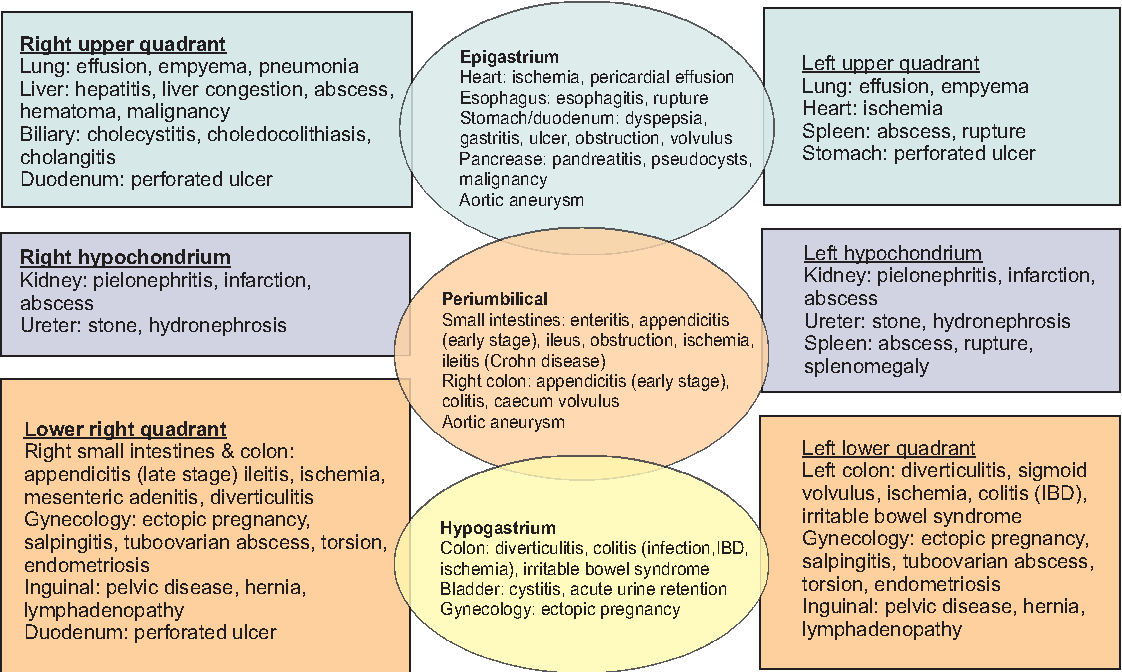

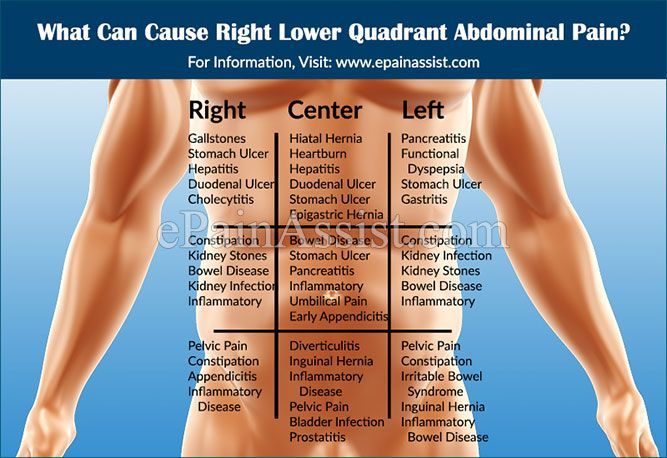

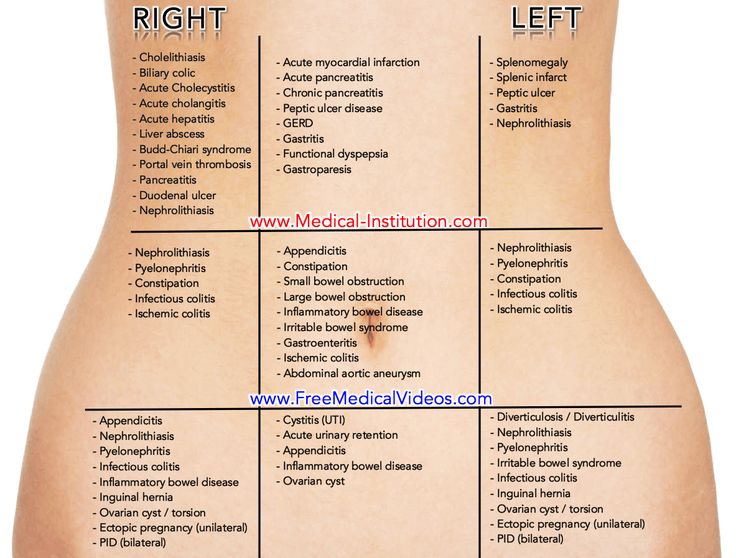

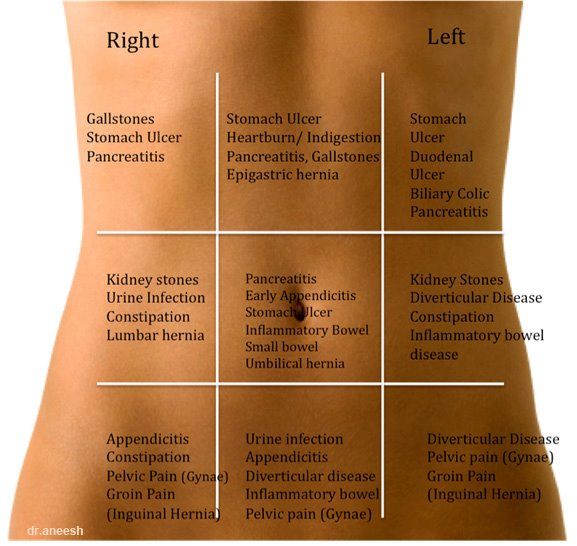

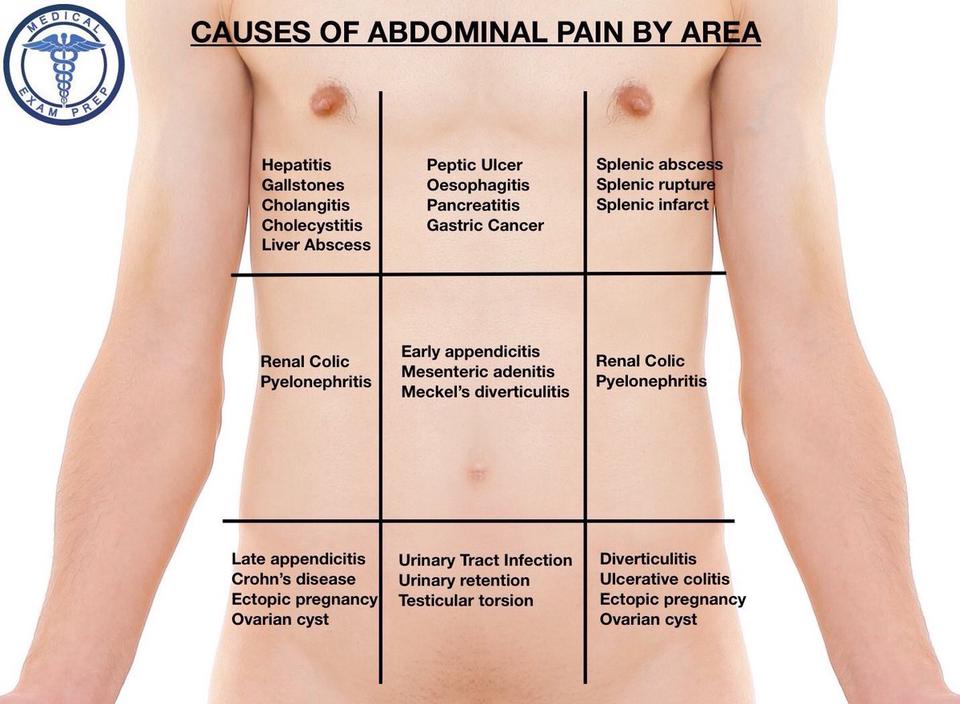

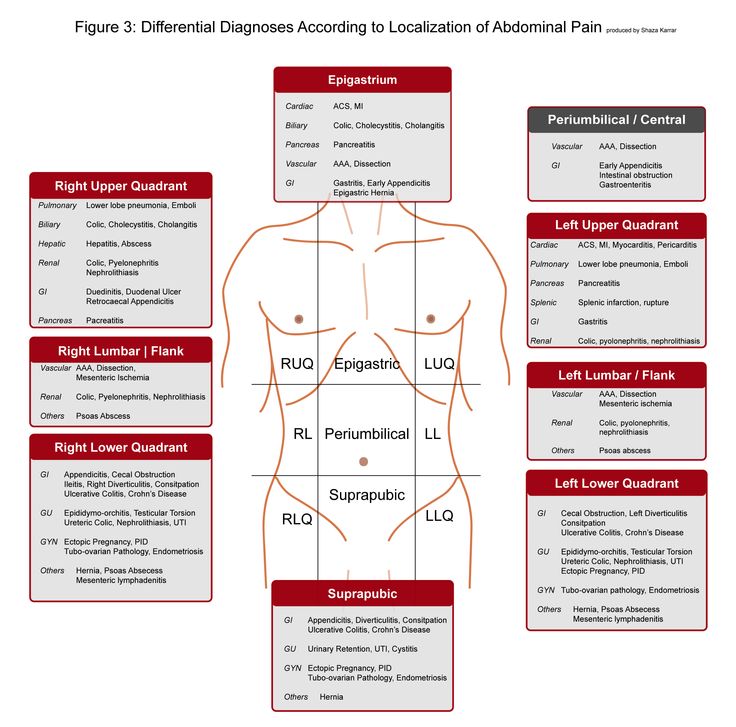

Palpation: Focus on locating the site of tenderness, signs of peritonism and palpation of masses. Abdomen is divided into right upper, right lower, left upper and left lower quadrants. Localisation of tenderness guides physician to generate differential diagnosis pertaining to that area. However, one can have diffuse abdominal pain spreading to more than one quadrant, i.e. pain of renal calculus extends from lumbar region to the iliac fossa and groin.

Patients with peritoneal irritation show tenderness, guarding/rigidity and pain with coughing. Guarding could be voluntary or involuntary. Due to lax abdominal wall musculature, guarding and rigidity may be absent in the elderly. Typical rebound tenderness is no longer considered an important examination tool due to painful procedure [1].

Guarding could be voluntary or involuntary. Due to lax abdominal wall musculature, guarding and rigidity may be absent in the elderly. Typical rebound tenderness is no longer considered an important examination tool due to painful procedure [1].

Abdominal aorta, liver and spleen sizes can be evaluated by palpation. Elderly patients with history of recent abdominal/flank/low back pain, known hypertension, pulsatile abdominal mass and feeble/absent distal pulses are suggestive of abdominal aortic aneurysm/dissection. Bedside ultrasound facilitates visualisation of increased abdominal aortic diameter and determines further surgical/medical management.

Percussion: Helpful to assess free air intraperitoneum, degree of ascites, gas-filled bowel loops and peritonitis. It is not very useful in noisy ED.

Auscultation: It gives information regarding bowel and vascular status. Absent or diminished bowel sound indicates ileus, mesenteric ischaemia, narcotic use or peritonitis. Hyperactive bowel sounds suggest small bowel obstruction, enteritis or early ischaemic intestine. High pitched tinkling sound reflects mechanical obstruction.

Hyperactive bowel sounds suggest small bowel obstruction, enteritis or early ischaemic intestine. High pitched tinkling sound reflects mechanical obstruction.

Digital rectal examination: Useful for detection of perianal and rectal pathologies (haemorrhoids, fissure and fistula), intraluminal intestinal haemorrhage (dark maroon/red stool), proctitis and constipation (faecal impaction and intestinal obstruction). It is no more useful in diagnosing acute appendicitis [2].

Emergency physicians should be vigilant and think of serious pathology in presence of any of the following clinical features:

Abdominal pain prior to vomiting

Haematemesis/haematochezia

Confusion

Toxic appearance

Signs of shock/dehydration

Localised/generalised tenderness

Guarding/rigidity

Absent bowel sound

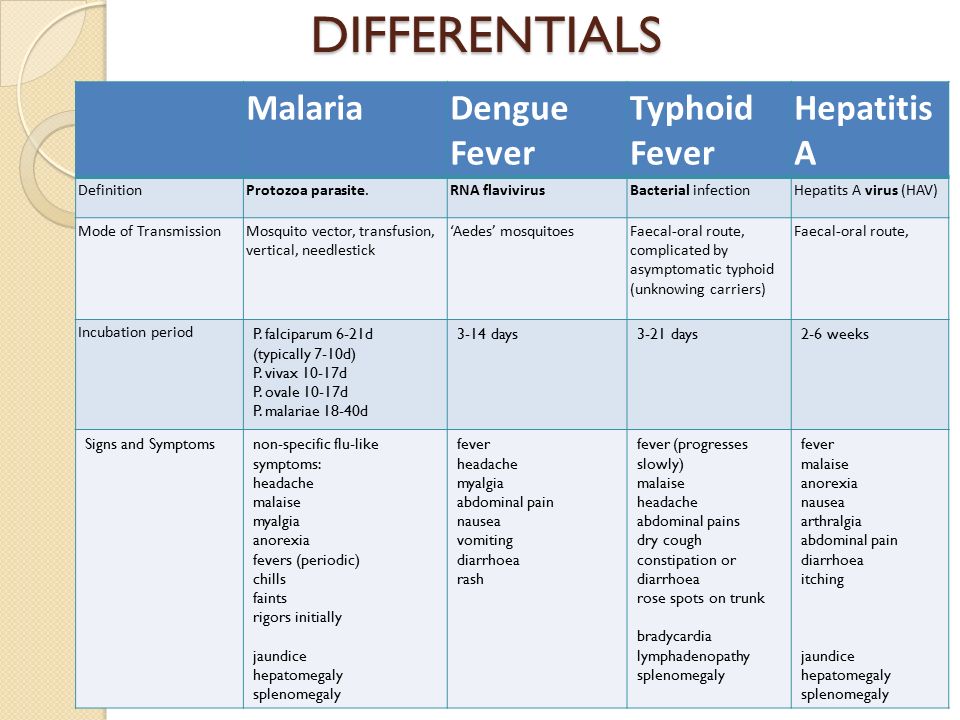

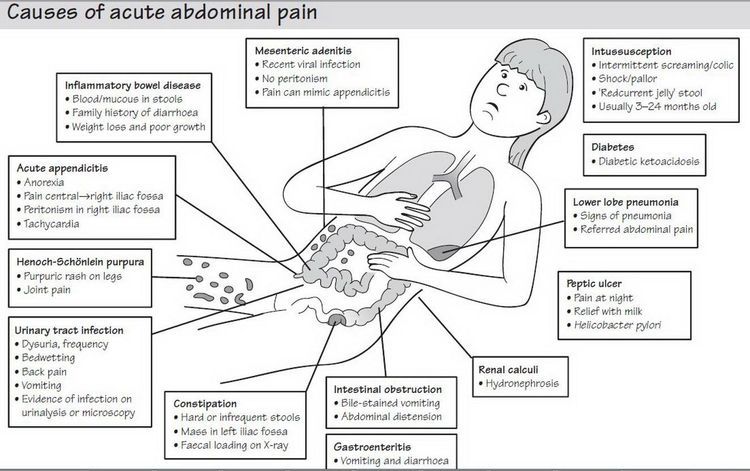

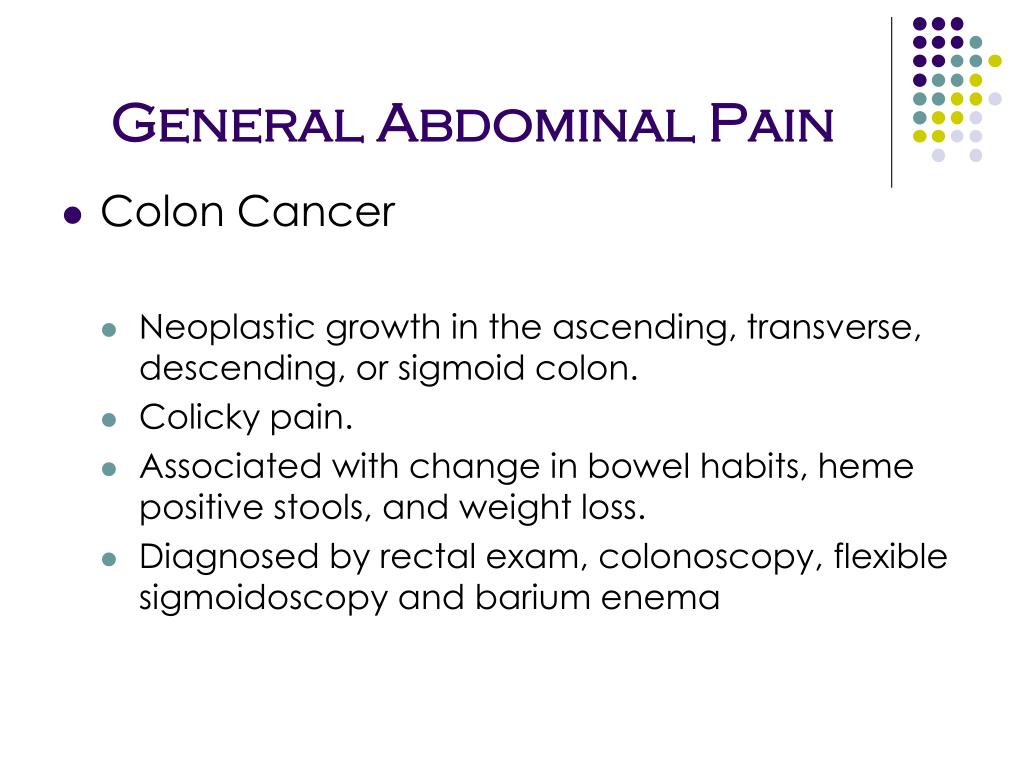

Extensive differential considerations ranging from simple nonspecific abdominal pain to severe life-threatening conditions are mentioned in Table .

Important differential diagnosis

| Condition | Epidemiology | Clinical features | Laboratory tests | Imaging | Complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute gastritis | Any age | Epigastric burning pain, associated with food, increases on supine position | – | Upper GI endoscopy, biopsy for H. pylori | Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, perforation |

| Epigastric tenderness, no rebound tenderness | |||||

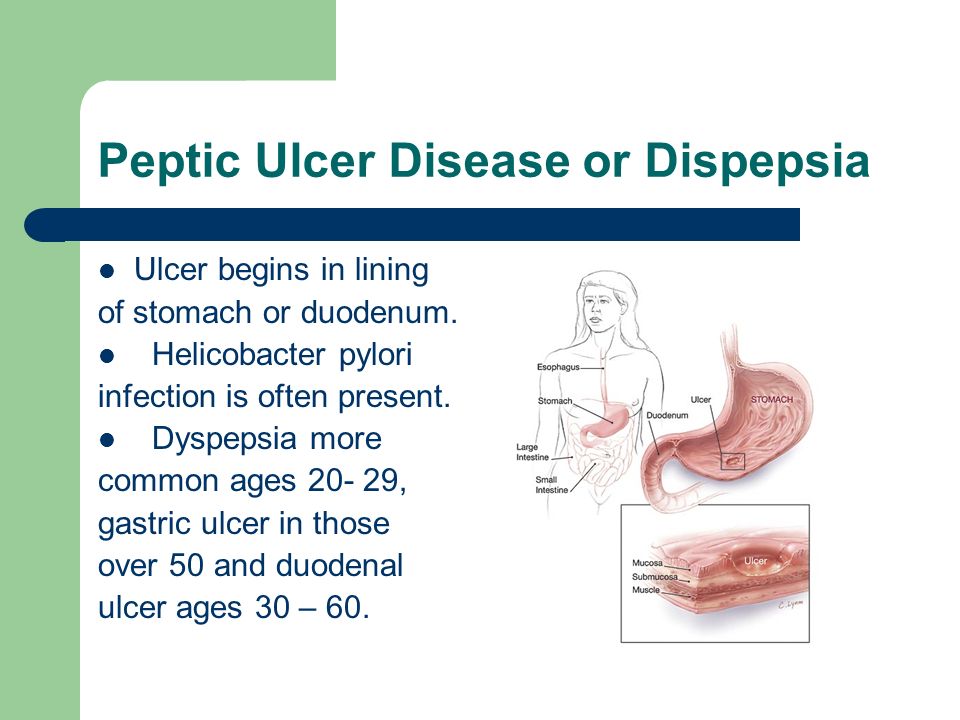

| Peptic ulcer disease | Age >50 years, M>F, RF: H. pylori, NSAIDS use, smoking, alcohol pylori, NSAIDS use, smoking, alcohol | Severe epigastric pain 2–5 h after meals or at night, nausea, vomiting, early satiety | Stool for occult blood (bleeding ulcer) | Upper GI endoscopy | Perforation, bleeding |

| Epigastric tenderness | |||||

| Biliary tract disease | Age: 40–60 years, F>M, RF: childbearing age, obese, alcohol, OC pills | Epigastric/RUQ pain, radiating to right shoulder/subscapular, postprandial pain, nausea, fever | CBC, liver function test | Ultrasonography – most sensitive, CT scan in extrahepatic biliary obstruction, hepatobiliary scintigraphy | Septicaemia, pancreatitis |

| Jaundice, RUQ tenderness, rebound tenderness, Murphy’s sign | |||||

| Acute pancreatitis | Age: 45–60 years, varies with aetiology; M>F, aetiology: gallstones, alcohol | Severe epigastric pain following meal, radiating to back, nausea, vomiting, fever, tachycardia, tachypnoea, hypotension, hyperthermia, epigastric tenderness, guarding, Cullen’s sign, Grey Turner’s sign | CBC, S. lipase, S. amylase, liver function test lipase, S. amylase, liver function test | Helical CT with contrast, ultrasonography for biliary tract pathology | Local complications: acute local fluid collection, pseudocyst, necrosis, abscess |

| Systemic: septicaemia, ARDS | |||||

| Bowel obstruction | Any age, RF: h/o previous abdominal surgery | Crampy abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, constipation, abdominal distension | CBC, S. electrolytes | X-ray abdomen standing, CT abdomen | Strangulation, incarceration |

| Tachycardia, diffuse tenderness, tympanic note, hyperactive bowel sound, PR examination – empty | |||||

| Viscus perforation | Elderly age, RF: peptic ulcer, intestinal ulcers, carcinoma | Severe abdominal pain, lies still in bed, abdominal distension, vomiting, fever | CBC, S. electrolytes electrolytes | X-ray chest, abdomen standing | Septicaemia |

| Signs of shock, generalized abdominal tenderness, rigidity, signs of peritonitis | |||||

| Mesenteric ischaemia | Elderly population, M>F, RF: atherosclerosis, arrhythmia, CHF, recent MI, valvular diseases | Diffuse abdominal pain out of proportion, vomiting, diarrhoea | CBC, S. lactate, blood pH, S. amylase, S. creatinine kinase | CT abdominal angiography | Intestinal necrosis, metabolic acidosis |

| Tachycardia, tachypnoea, hypotension, silent abdomen initially, signs of peritonitis | |||||

| Diverticulitis | Mean age: 60 years, M=F, sigmoid colon – most common site | Left lower quadrant pain, fever, change in bowel habits | CBC, stool for occult blood | CT abdomen | Perforation, fistula, obstruction, haemorrhage |

| Abdominal tenderness, guarding, signs of peritonitis | |||||

| Appendicitis | Young adulthood, M>F | Periumbilical pain migrates to RLQ, nausea, vomiting, fever | CBC, S. electrolytes, urine examination electrolytes, urine examination | CT in adult and non-pregnant patients | Perforation, peritonitis, septicaemia, abscess |

| RLQ tenderness, guarding, rebound tenderness, psoas sign, obturator sign | |||||

| Ureteric colic | Age: 30–40 years, M>F | Severe colicky flank pain radiating to groin, nausea, vomiting, haematuria, tossing up in bed | Urine examination, CBC | Spiral CT, ultrasonography in pregnancy | UTI |

| Flank tenderness | |||||

| Ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm | Age >50 years, M>F, RF: hypertension, atherosclerotic disease, DM, smoking family history | Severe sudden onset abdominal pain radiating to back, syncope, GI bleeding, shock | – | Bedside ultrasonography, CT aortogram | Shock, limb ischaemia |

| Tachycardia, hypotension, palpable abdominal mass, unequal femoral pulses | |||||

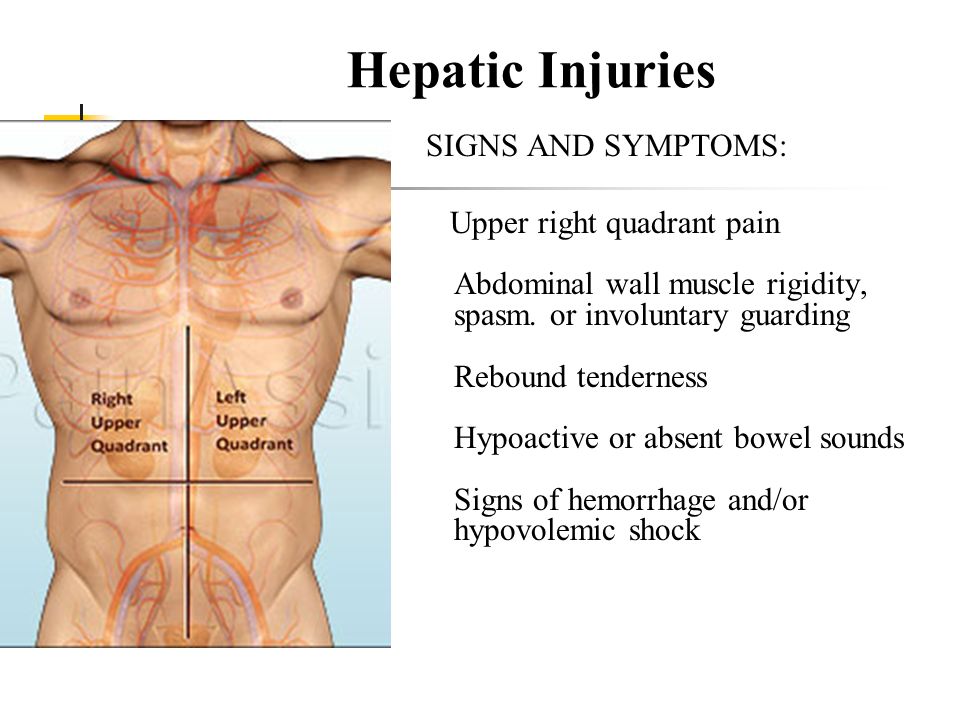

| Traumatic organ rupture | Age:15–35 years; M>F | Abdominal pain, vomiting | CBC | EFAST, abdominal sonography, CT abdomen | Shock, peritonitis, DIC |

| Signs of shock, injury marks | |||||

| Ruptured ectopic pregnancy | Female of childbearing age, RF: IUCD, previous ectopic, PID | Sudden, severe pain, spotting, amenorrhoea | UPT, S. HCG, CBC HCG, CBC | FAST, transvaginal and transabdominal ultrasonography | Shock, septicaemia, DIC |

| Tachycardia, hypotension, peritoneal signs, adnexal mass and tenderness, cervical motion tenderness, blood in vaginal vault | |||||

| PID | Age: 15–49 years; RF: multiple partners, previous PID | Lower abdominal pain, fever, nausea, vomiting, vaginal discharge | UPT, CBC, vaginal swab test for gonorrhoea/chlamydia | Transvaginal ultrasonography | Tubo-ovarian abscess, ectopic pregnancy |

| Cervical motion/uterine/adnexal tenderness, rebound tenderness | |||||

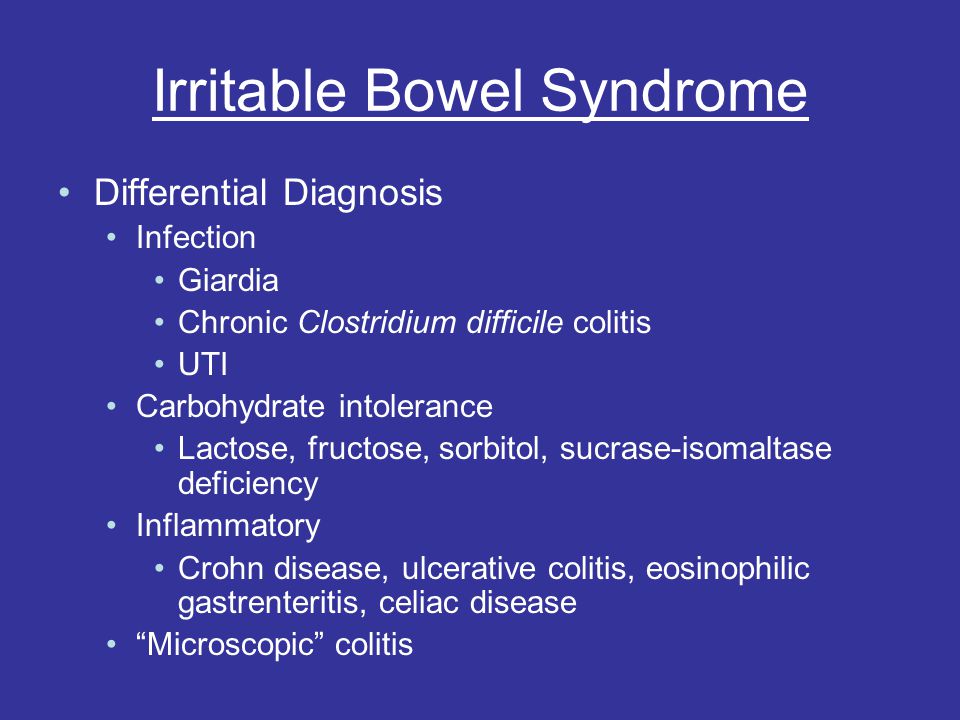

| C. difficile colitis | Elderly population, RF: antibiotics (fluoroquinolones, penicillin, clindamycin) | Crampy abdominal pain, watery diarrhoea, fever | CBC, Stool culture | CT scan | Pseudomembranous colitis, toxic megacolon, perforation |

| Signs of dehydration, abdominal tenderness, distension, rebound tenderness, marked rigidity, decreased bowel sound |

Open in a separate window

> – more, = – equal, ARDS acute respiratory distress syndrome, CBC complete blood count CHF congestive heart failure, CT computed tomography, DIC disseminated intravascular coagulation, EFAST extended focused abdominal sonography in trauma, F female, HCG human chorionic gonadotropin, HIV human immunodeficiency virus, IUCD intrauterine copper device, M male, MI myocardial infarction, NSAIDs non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, PID pelvic inflammatory disease, PR per rectum, RF risk factors, RLQ right lower quadrant, RUQ right upper quadrant, UPT urinary pregnancy test, UTI urinary tract infection

It is essential to suspect life-threatening conditions (Box 26. 1) in haemodynamically unstable. Early resuscitation and stabilisation should be followed by investigations and hospitalisation of such patients.

1) in haemodynamically unstable. Early resuscitation and stabilisation should be followed by investigations and hospitalisation of such patients.

| Acute intestinal obstruction |

| Viscus perforation |

| Traumatic rupture of the spleen/liver/bowel |

| Acute pancreatitis |

| Mesenteric ischaemia |

| Ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm |

| Ruptured ectopic pregnancy |

| Myocardial infarction |

Open in a separate window

Women of reproductive age group with abdominal pain should undergo pregnancy test and seek gynaecological consult and bedside ultrasonography if necessary. Consider ectopic pregnancy in such patients unless proven otherwise.

It is not necessary to reach proper diagnosis despite availability of various tests. It is incumbent to consider extra-abdominal causes (Table ) in such patients before considering it as nonspecific.

Extra abdominal causes [3]

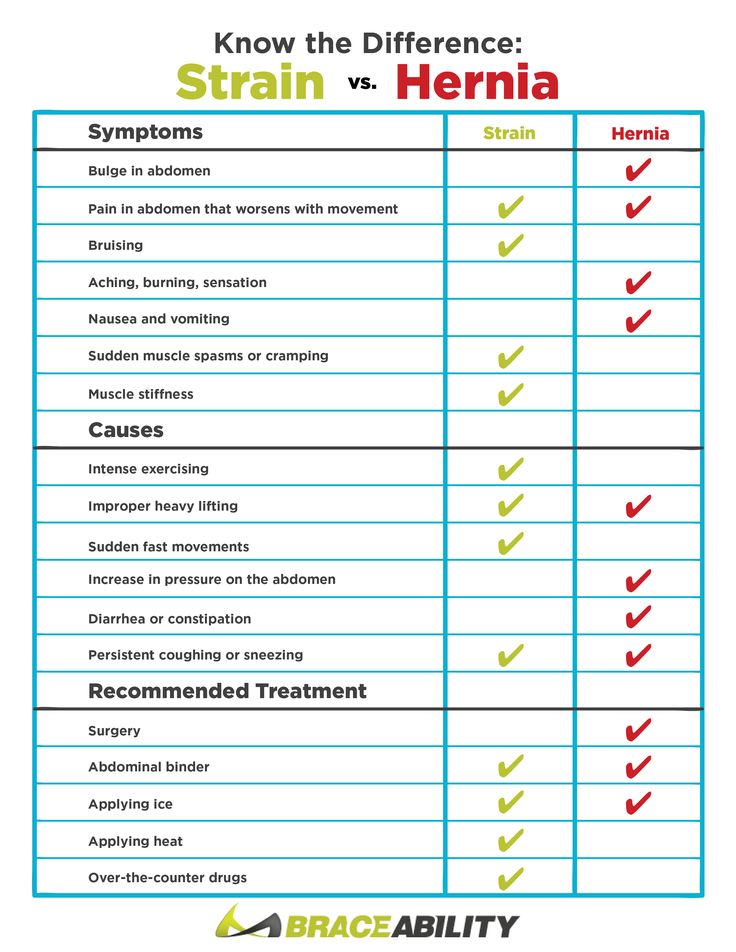

| Abdominal wall | Muscle spasm/haematoma |

| Herpes zoster | |

| Systemic | Alcoholic/diabetic ketoacidosis |

| Sickle cell disease | |

| Porphyria | |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | |

| Uraemia | |

| Thoracic | Myocardial infarction myocarditis/pericarditis |

| Pulmonary embolism | |

| Pneumonia | |

| Toxicology | Lead/iron poisoning |

| Snake/scorpion bite | |

| Black widow spider bite | |

| Genitourinary | Testicular torsion |

| Infections | Mononucleosis |

| Rocky mountain spotted fever | |

| Streptococcal pharyngitis |

Open in a separate window

2 Routine Laboratory Workup

2 Routine Laboratory Workup| Haematocrit: GI bleed |

| WBC count: infection/inflammation, though of limited value [4, 5] |

| Platelet count: bleeding disorders |

| Liver profile: hepatitis, cholecystitis, post hepatic biliary tract obstruction |

| Coagulation profile: status of coagulopathy, bleeding disorders, trauma |

| Renal profile: prerenal, renal or post renal failure, degree of dehydration, renal insufficiency, electrolyte imbalance |

| Pancreatic enzymes: pancreatitis, other pancreatic pathologies. Lipase is more sensitive when it is 3 times higher than normal value [6] |

| Serum lactate level: mesenteric ischaemia, bowel infarction. May be normal in 25 % of patients with intestinal ischaemia [7] |

| Serum glucose: pancreatitis, diabetic/alcoholic ketoacidosis |

| Urine analysis: UTI, nephrolithiasis, pyelonephritis, cystitis, renal parenchymal disorders |

| Urine sugar/ketone dipstick: diabetic ketoacidosis |

| Urine culture: UTI |

| Urine pregnancy test: females in reproductive age group |

| Stool for occult blood: upper GI bleed |

| Stool culture, stool for ova and hanging drop test: diarrhoea |

Open in a separate window

Computed tomography: It is sensitive and accurate in diagnosing acute appendicitis, bowel wall diseases, solid organs, urinary tract calculi, mesenteric ischaemia and retroperitoneal structures. It is useful in differentiating mechanical vs. paralytic bowel obstruction.

It is useful in differentiating mechanical vs. paralytic bowel obstruction.

CT scan of abdomen has become an imaging modality of choice. Intraperitoneal and extraperitoneal structures can be visualised through CT scan. It helps to reduce morbidity and mortality. Elderly people are more prone to undergo surgery and have higher mortality than young patients. Moreover, history, vital signs and physical examination are not reliable in elderly due to comorbid conditions and medication use [10].

CT scan is associated with radiation risk. Improved technology and better image resolution have made oral contrast obsolete, and pathologies of solid organ and bowel wall are detected with intravenous contrast only [11] (Fig. ).

Open in a separate window

CT abdomen with contrast film showing multiple air fluid levels suggestive of intestinal obstruction

Recommended imaging studies based on location of abdominal pain is shown in Table .

Recommended imaging test depending on the site of abdominal pain

| Right upper quadrant [12] | Ultrasonography |

| Left upper quadrant | CT scan |

| Right lower quadrant [13] | CT scan with contrast |

| Left lower quadrant [14] | CT scan with contrast |

| Suprapubic | Ultrasonography |

Open in a separate window

CT computed tomography

Electrocardiogram is essential especially in elderly people with risk factors.

Therapeutic goals for acute abdominal pain patients are primary stabilisation, mitigation from symptoms, diagnosis and treatment of cause.

Haemodynamic instability may be present in patients with following features:

Extremes of age

Immunocompromised state

Abnormal vital signs

Signs of dehydration

Early resuscitation and identification of primary cause are the mainstay of treatment. This includes (OMIV): O, oxygen; M, cardiac monitor; IV, large bore IV lines; and V, vitals. Blood samples should be collected for routine investigations. Blood transfusion should be anticipated in haemorrhagic conditions (ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm, massive GI haemorrhage, ruptured ectopic pregnancy, traumatic spleen rupture). Bedside ultrasound helps in identification of undifferentiated shock. These patients require prompt surgical consultation.

Early pain management doesn’t mask physical findings, delay diagnosis or increase morbidity and mortality. Analgesics in the form of paracetamol, NSAIDs and opioids like fentanyl or morphine are used depending on pain score. Cope’s early diagnosis of acute abdomen [15] favours opioid analgesia in abdominal pain patients.

Analgesics in the form of paracetamol, NSAIDs and opioids like fentanyl or morphine are used depending on pain score. Cope’s early diagnosis of acute abdomen [15] favours opioid analgesia in abdominal pain patients.

Antacids relieve burning pain due to gastric acid production [16]. Antiemetics like ondansetron and metoclopramide are useful in remitting nausea and vomiting. NG tube is essential in patients with small bowel obstruction to decompress stomach and provide symptomatic relief. Metoclopramide has extrapyramidal side effects.

Administration of antibiotics is useful in cessation of disease process and early recovery. Antibiotics should cover gram-negative anaerobic and aerobics and extended to gram-positive pathogens too. Table shows some commonly used regimens.

Useful antibiotic regimen

| Uncomplicated infective conditions | Second generation cephalosporins |

| Cefotaxime 1 g IV 12 hourly | |

| Immunocompromised, elderly, hypotensive | Aminoglycosides |

(Gentamicin/tobramycin 1. 5 mg/kg IV 8 hourly) 5 mg/kg IV 8 hourly) | |

| + | |

| Metronidazole 400 mg IV 8 hourly | |

| Suspected biliary sepsis | Piperacillin tazobactam 4.5 g IV 12 hourly |

| Suspected bacterial peritonitis | Ceftriaxone 1 g IV 12 hourly |

| PID | Doxycycline 100 mg PO 12 hourly for 14 days |

| Metronidazole 400 mg PO 12 hourly for 14 days | |

| Clostridium difficile colitis | Metronidazole 400 mg PO 8 hourly for 14 days |

| Vancomycin 500 mg/day PO for 4 days | |

| H. pylori gastritis [17] | Amoxicillin 1,000 mg PO 12 hourly + |

| Clarithromycin 500 mg PO 12 hourly + | |

| Omeprazole 20 mg PO 12 hourly for 14 days |

Open in a separate window

IV intravenous, PO per oral

Decision to discharge is as difficult as diagnosis of acute abdominal pain. Various available options are:

Various available options are:

Admission and surgical/nonsurgical consultation

Admission for observation

Discharge with follow-up advice

Indications for hospitalisation:

Elderly and immunocompromised

Intractable nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain

Appears ill with unclear diagnosis

Intolerable oral intake

Abnormal physical examination (signs of peritonitis)

Poor social support

Patients with less severe symptoms without specific diagnosis need laboratory/radiological evaluation and observation for 8–10 h in ED. Follow-up with primary care physician in 12 h is another valid option.

Stable asymptomatic patients can be discharged from emergency. Discharge criteria may include:

Asymptomatic

No abnormal clinical features

Normal vital signs

Tolerate oral intake

Adequate social support at home

Patients should be given proper diet advice and safety instructions.

1. Macaluso CR, McNamara RM. Evaluation and management of acute abdominal pain in the emergency department. Int J Gen Med. 2012;5:789–97. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S25936. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

2. Brewster GS, Herbert ME. Medical myth: a digital rectal examination should be performed on all individuals with suspected appendicitis. West J Med. 2000;173:207–8. doi: 10.1136/ewjm.173.3.207. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

3. Purcell TB. Nonsurgical and extraperitoneal causes of abdominal pain. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1989;7:721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Bundy DG, Byerley JS, Liles EA, et al. Does this child have appendicitis? JAMA. 2007;298:438–51. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.4.438. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

5. Kessler N, Cyteval C, Gallix B, et al. Appendicitis: evaluation of sensitivity, specificity, and predictive value of US, Doppler US, and laboratory findings. Radiology. 2004;230:472–8. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2302021520. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

doi: 10.1148/radiol.2302021520. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

6. Chang JWY, Chung CH. Diagnosing acute pancreatitis: amylase or lipase? Hong Kong J Emerg Med. 2011;18(1):20–5. [Google Scholar]

7. Kassahun WT, Schulz T, Richter O, Hauss J. Unchanged high mortality rates from acute occlusive intestinal ischemia: six year review. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2008;393:163. doi: 10.1007/s00423-007-0263-5. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

8. Miller RE, Nelson SW. The roentgenologic demonstration of tiny amounts of free intraperitoneal gas: experimental and clinical studies. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1971;112:574–85. doi: 10.2214/ajr.112.3.574. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

9. Spence SC, Teichgraeber D, Chandrasekhar C. Emergent right upper quadrant sonography. J Ultrasound Med. 2009;28:479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Esses D, et al. Ability of CT to alter decision making in elderly patients with acute abdominal pain. Am J Emerg Med. 2004;22:270. doi: 10. 1016/j.ajem.2004.04.004. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

1016/j.ajem.2004.04.004. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

11. Lee SY, et al. Prospective comparison of helical CT of the abdomen and pelvis without and with oral contrast in assessing acute abdominal pain in adult emergency department patients. Emerg Radiol. 2006;12:150. doi: 10.1007/s10140-006-0474-z. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

12. Bree RL, Foley WD, Gay SB, et al., for the Expert Panel on Gastrointestinal Imaging. American College of Radiology ACR Appropriateness Criteria. Right upper quadrant pain. http://www.acr.org/SecondaryMainMenuCategories/quality_safety/app_criteria.aspx. Accessed 24 Aug 2007.

13. Bree RL, Blackmore CC, Foley WD, et al., for the Expert Panel on Gastrointestinal Imaging. American College of Radiology ACR Appropriateness Criteria. Right lower quadrantpain. http://www.acr.org/SecondaryMainMenuCategories/quality_safety/app_criteria.aspx. Accessed 24 Aug 2007.

14. Levine MS, Bree RL, Foley WD, et al., for the Expert Panel on Gastrointestinal Imaging. American College of Radiology ACR Appropriateness Criteria. Left lower quadrantpain. http://www.acr.org/SecondaryMainMenuCategories/quality_safety/app_criteria.aspx. Accessed 24 Aug 2007.

American College of Radiology ACR Appropriateness Criteria. Left lower quadrantpain. http://www.acr.org/SecondaryMainMenuCategories/quality_safety/app_criteria.aspx. Accessed 24 Aug 2007.

15. Silen W. Cope’s early diagnosis of the acute abdomen. 21. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

16. Berman DA, Porter RS, Graber M. The GI cocktail is no more effective than plain liquid antacid: a randomized, double blind clinical trial. J Emerg Med. 2003;25:239. doi: 10.1016/S0736-4679(03)00196-3. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

17. Chey WD, et al. American College of Gastroenterology guideline on the management of H. Pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1808–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01393.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

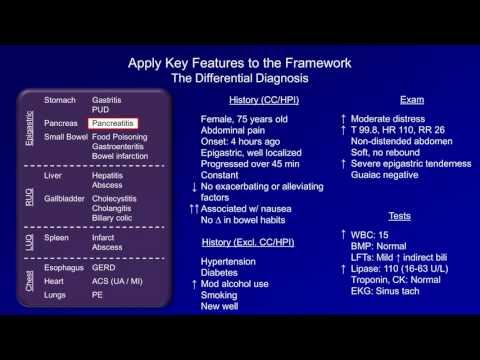

Case Study: A 43 year-old female with a past medical history of cesarean section presents with four hours of abdominal pain. Pain is located in the right upper quadrant with radiation to the epigastrium and associated with 2 episodes of nonbloody, nonbilious emesis. She ate a cheeseburger with fries and had two beers shortly before the onset of pain. She has had pain like this in the past but this is the first time it has persisted despite acetaminophen. She has no family history, drinks 8-9 alcoholic beverages per week, and is sexually active with her husband. On examination, her vitals are within normal limits and stable and she has tenderness to palpation to the right upper quadrant (positive Murphy’s) without rebound or peritoneal signs. She has no CVA tenderness or lower abdominal tenderness. The remainder of her examination is normal.

Pain is located in the right upper quadrant with radiation to the epigastrium and associated with 2 episodes of nonbloody, nonbilious emesis. She ate a cheeseburger with fries and had two beers shortly before the onset of pain. She has had pain like this in the past but this is the first time it has persisted despite acetaminophen. She has no family history, drinks 8-9 alcoholic beverages per week, and is sexually active with her husband. On examination, her vitals are within normal limits and stable and she has tenderness to palpation to the right upper quadrant (positive Murphy’s) without rebound or peritoneal signs. She has no CVA tenderness or lower abdominal tenderness. The remainder of her examination is normal.

By the end of this module, the student will be able to:

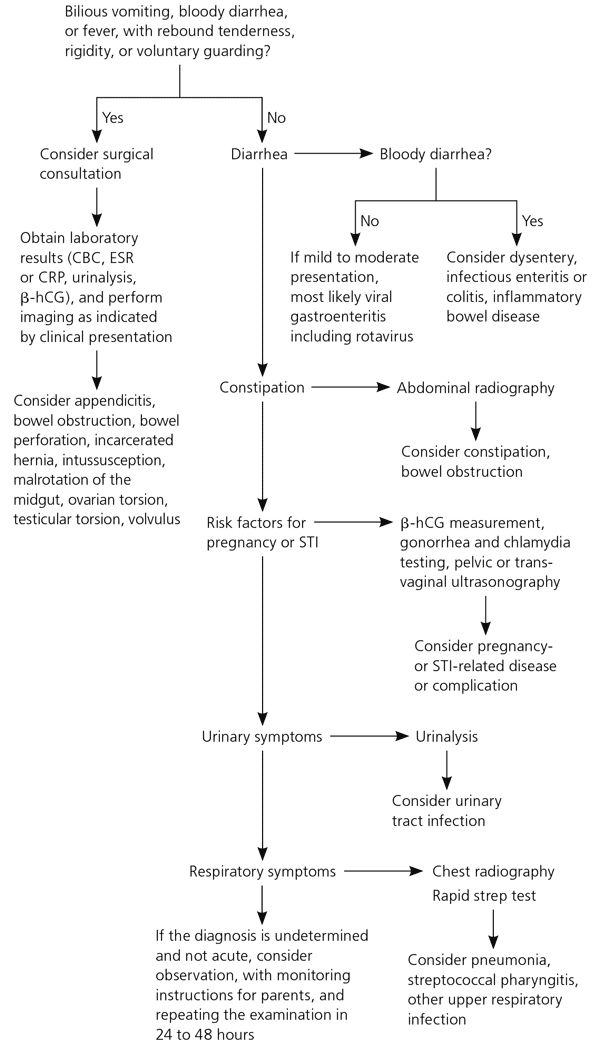

Abdominal pain is the most common emergency department (ED) chief complaint in adult patients. In the US, abdominal pain is responsible for more than 7 million ED visits per year. Despite this frequency, it remains a challenging complaint due to the large number of possible etiologies and widely variable clinical presentations. While a specific diagnosis is frequently difficult to make in the ED (approximately 25% of presenting patients are ultimately diagnosed with ‘nonspecific abdominal pain’), it is imperative that the emergency physician exclude time-dependent disease processes that if left undiagnosed could lead to morbidity or mortality.

In the US, abdominal pain is responsible for more than 7 million ED visits per year. Despite this frequency, it remains a challenging complaint due to the large number of possible etiologies and widely variable clinical presentations. While a specific diagnosis is frequently difficult to make in the ED (approximately 25% of presenting patients are ultimately diagnosed with ‘nonspecific abdominal pain’), it is imperative that the emergency physician exclude time-dependent disease processes that if left undiagnosed could lead to morbidity or mortality.

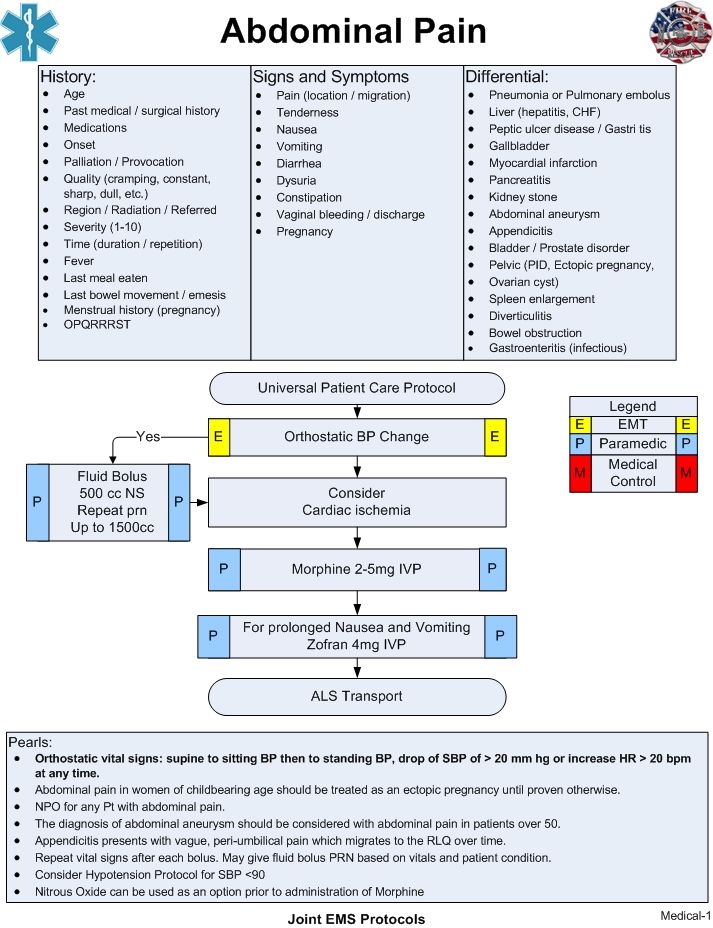

A primary assessment and evaluation of ABCs must be completed on any patient presenting to the emergency department with abdominal pain. While airway compromise and respiratory insufficiency can develop in a patient suffering from an abdominal catastrophe, the circulatory system most commonly needs the attention of the clinician in the setting of abdominal pain.

Abdominal pain in conjunction with hemodynamic instability should alert the physician to the possibility of hemorrhage, sepsis, perforated viscus, or necrotic bowel. Tachycardia or orthostatic vital signs are often the first sign of hemodynamic instability; it requires blood loss of 30-40% of normal blood volume to cause a significant drop in systolic blood pressure. In patients with established hemodynamic instability, immediate fluid resuscitation should begin by establishing 2 large bore IVs and rapidly infusing isotonic crystalloid. Supplemental oxygen should be administered, and patients should be placed on a monitor.

Tachycardia or orthostatic vital signs are often the first sign of hemodynamic instability; it requires blood loss of 30-40% of normal blood volume to cause a significant drop in systolic blood pressure. In patients with established hemodynamic instability, immediate fluid resuscitation should begin by establishing 2 large bore IVs and rapidly infusing isotonic crystalloid. Supplemental oxygen should be administered, and patients should be placed on a monitor.

The primary survey of patients with abdominal pain should include a brief history evaluating for symptoms of infection, bleeding diathesis, and the possibility of pregnancy; an abdominal examination should be performed for the presence of peritonitis, as this indicates a patient requiring more immediate surgical intervention.

In the unstable patient with abdominal pain in whom hemorrhage is diagnosed or highly suspected, typed and crossed blood should be immediately ordered. The transfusion of type O blood can be performed in critical situations where there is not enough time to wait for cross matched blood.

Women of childbearing age who present with abdominal pain require urgent pregnancy testing to rule out ectopic pregnancy. When such a patient is unstable, rapidly obtain either urine serum for qualitative beta-HCG testing. If the patient is pregnant, blood should also be sent for a quantitative beta-HCG level.

Patients with abdominal pain have a wide range of potential presentations. A thorough history will catch potentially challenging diagnoses in otherwise unrevealing presentations. A clear description of the pain itself is often quite helpful in narrowing down the cause of abdominal pain. Elicit:

For example, pain that is constant, originally located in the periumbilical area but now migrated to the right lower quadrant, and palliated by staying still is quite different than a pain that is located in the epigastrium with radiation to the right upper quadrant, worsened with oral intake, and associated with fever and vomiting.

In addition to evaluation of the pain, a brief evaluation of the patient’s previous medical, surgical history, and risk factors may increase your suspicion for particular pathologies. A medical history of diabetes or HIV may result in an atypical presentation of a common complaint. A history of abdominal surgeries or hernias increases the likelihood of bowel obstruction. The social history of a patient with abdominal pain can also be similarly illustrative. Sexual activity puts the patient at risk for sexually transmitted infections and, in the case of the female patient, ectopic pregnancy. A recent diet of highly acidic food, food with significant fats, or alcohol can increase the patient’s risk of gastritis, cholecystitis, or pancreatitis respectively. Ask your patient about similar episodes and associated diagnostics and treatments.

A thorough abdominal examination includes inspection, auscultation, and palpation. Inspect the patient for surgical scars and evidence of distension. Auscultate for bowel sounds is not considered to be diagnostic and can be unreliable. Palpation should focus on the presence or absence of rigidity and the location of primary tenderness, as this will help guide the differential diagnosis. The presence of a Murphy’s sign in the right upper quadrant may suggest gallbladder pathology. Tenderness at McBurney’s point in the right lower quadrant may suggest appendicitis.

Auscultate for bowel sounds is not considered to be diagnostic and can be unreliable. Palpation should focus on the presence or absence of rigidity and the location of primary tenderness, as this will help guide the differential diagnosis. The presence of a Murphy’s sign in the right upper quadrant may suggest gallbladder pathology. Tenderness at McBurney’s point in the right lower quadrant may suggest appendicitis.

In addition to palpation of the abdomen, the costovertebral angles should be percussed for evaluation of the kidneys. In the setting of lower abdominal pain, an evaluation of the genitalia should be completed. In males, this is relevant for referred pain secondary to testicular torsion, infection, or incarcerated hernia. In females, ovarian torsion, pelvic inflammatory disease, and ectopic pregnancy will often present as abdominal pain.

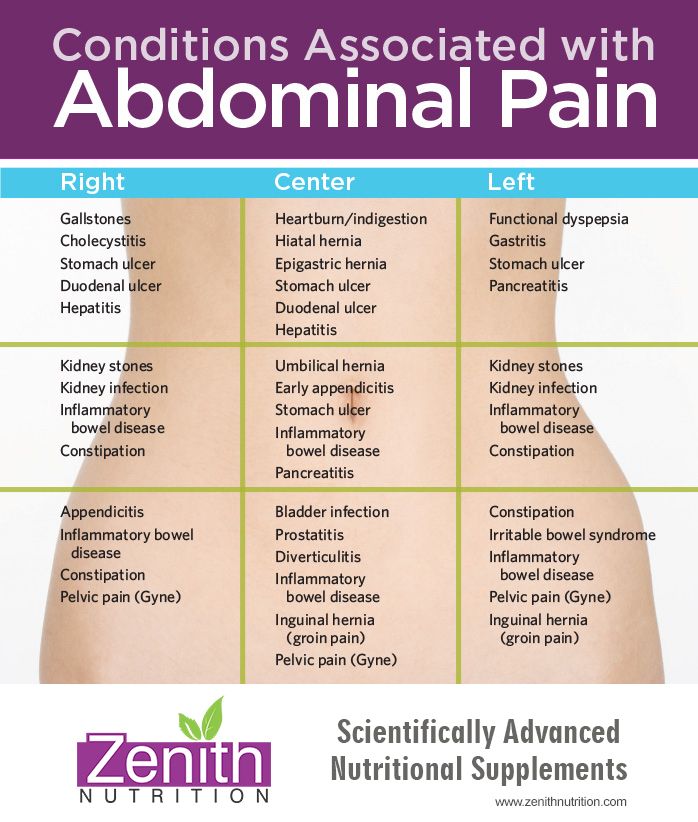

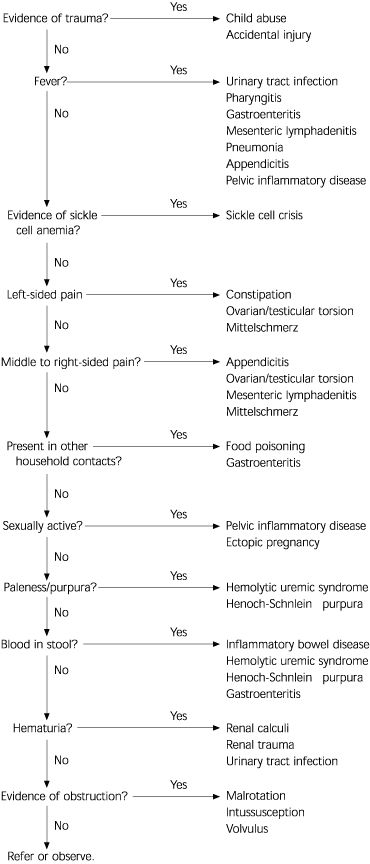

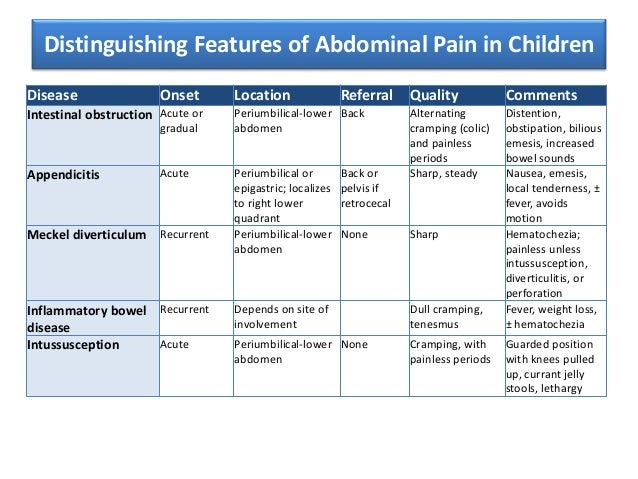

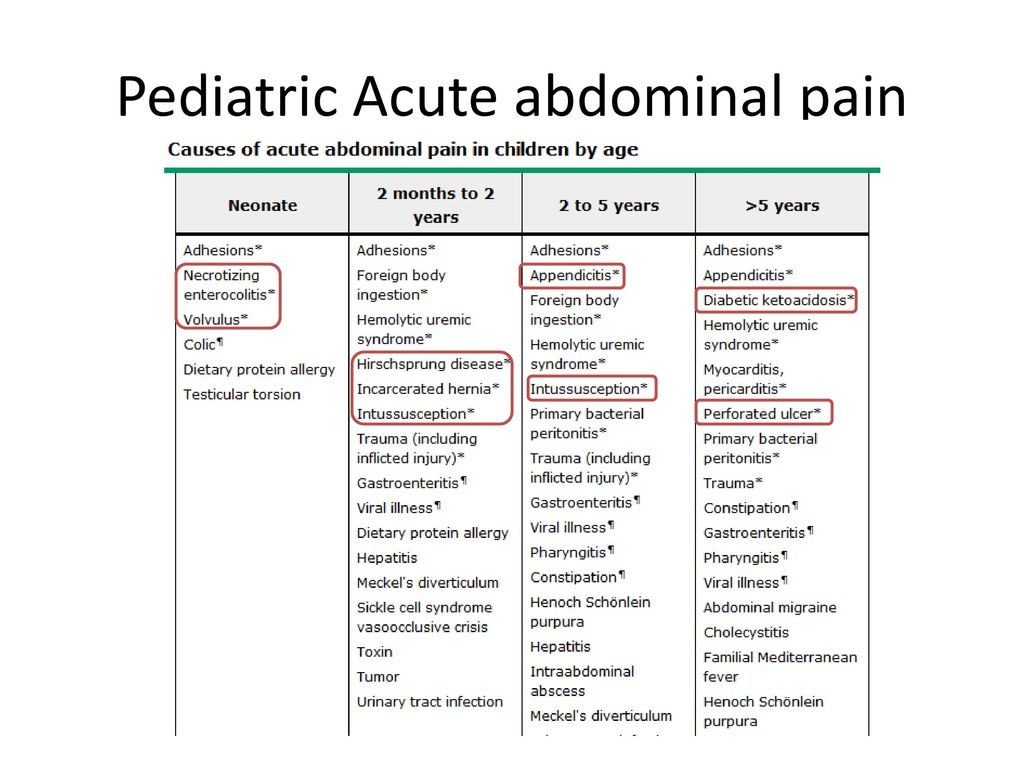

The most common approach to the diagnosis of abdominal pain focuses on the location of the pain, with a separate grouping for causes of diffuse abdominal pain. Two other factors that need to be considered up front with abdominal pain include sex and age. Although these lists are useful as an initial approach, it is important to remember that it is common to see diagnoses present with pain and tenderness where it isn’t expected. It is important to begin your differential diagnoses with the potential life-threatening or critical diagnoses in order to rule them out. These diagnoses are highlighted in the tables below and link to their chapters within the site.

Two other factors that need to be considered up front with abdominal pain include sex and age. Although these lists are useful as an initial approach, it is important to remember that it is common to see diagnoses present with pain and tenderness where it isn’t expected. It is important to begin your differential diagnoses with the potential life-threatening or critical diagnoses in order to rule them out. These diagnoses are highlighted in the tables below and link to their chapters within the site.

| Table 1: Differential Diagnosis of abdominal pain by location | |

| Right Upper Quadrant | Left Upper Quadrant |

|

|

| Right Lower Quadrant | Left Lower Quadrant |

|

|

Table 2: Differential Diagnosis for diffuse abdominal pain | |

|

|

Diagnostic testing should be guided by the patient’s history and physical examination findings which can be used to initially narrow the differential diagnosis. Standard “abdominal labs” are listed below, but should be tailored to the patient’s presentation. Refer to the Common Laboratory Studies chapter for further information about each test.

Standard “abdominal labs” are listed below, but should be tailored to the patient’s presentation. Refer to the Common Laboratory Studies chapter for further information about each test.

In addition to these labs, further labs that can be helpful in particular presentations of abdominal pain include: troponin, coagulation studies including prothrombin time and partial thromboplastin time, lactate, C reactive protein, and gonococcal/chlamydia testing.

Portable x-ray and ultrasound can serve as immediate diagnostic tools that can be performed at the bedside when there is concern for pneumoperitoneum or hemoperitoneum, respectively. An upright chest x-ray or lateral decubitus abdominal film has been demonstrated to reveal free air in 80% of cases with perforated viscus.

Ultrasound is an excellent tool for the evaluation of many urgent causes of abdominal pain. Bedside ultrasound can be used to search for abdominal free fluid suggestive of hemoperitoneum along with possible etiologies such as a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) or ruptured ectopic pregnancy. Bedside and radiology-performed ultrasound can also be diagnostic of nephrolithiasis, abdominal aneurysms, and in slender patients, appendicitis. An ultrasound verifying intrauterine pregnancy can help to rule out ectopic pregnancy in the case of the pregnant female. It may not entirely rule out ectopic or heterotopic pregnancy. Ultrasound is the diagnostic modality of choice for patients with suspected biliary pathology and ovarian and testicular torsion.

Bedside ultrasound can be used to search for abdominal free fluid suggestive of hemoperitoneum along with possible etiologies such as a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) or ruptured ectopic pregnancy. Bedside and radiology-performed ultrasound can also be diagnostic of nephrolithiasis, abdominal aneurysms, and in slender patients, appendicitis. An ultrasound verifying intrauterine pregnancy can help to rule out ectopic pregnancy in the case of the pregnant female. It may not entirely rule out ectopic or heterotopic pregnancy. Ultrasound is the diagnostic modality of choice for patients with suspected biliary pathology and ovarian and testicular torsion.

For patients presenting with concerning findings in whom ultrasound is unlikely to be diagnostic, CT should be considered. The use of CT scans can improve diagnosis and treatment of acute abdominal pain and decrease return visits by up to 30%. On the other hand, computed tomography carries significant radiation exposure and cost, can lead to false positives, and does not completely rule out all serious life-threatening illnesses causing abdominal pain.

Antibiotics: The abdomen is a frequent site of infection in the development of sepsis. Patients with abdominal pain who are found to be septic should receive early administration of antibiotics as part of their initial resuscitation. Antibiotics should also be given promptly to patients with peritonitis or a perforated viscus.

Antiemetics: Abdominal pain is frequently associated with nausea and vomiting. Two commonly used drugs for nausea and vomiting in the emergency department are ondansetron and metoclopramide and they have been demonstrated to be roughly equivalent in efficacy. Ondansetron is given 4-8 milligrams orally or intravenously every 4 hours; metoclopramide is given 10 milligrams intravenously, sometimes with the addition of diphenhydramine to prevent extrapyramidal side effects.

Analgesia: Patients presenting in significant abdominal discomfort and a history and physical suggesting a concerning diagnosis should be provided with immediate pain relief. Narcotic medication should not be withheld out of concern that the abdominal exam may become unreliable and the diagnosis therefore obscured. Fentanyl provides a nice option if a shorter acting agent is desired or if the blood pressure is tenuous.

Narcotic medication should not be withheld out of concern that the abdominal exam may become unreliable and the diagnosis therefore obscured. Fentanyl provides a nice option if a shorter acting agent is desired or if the blood pressure is tenuous.

Specialty Consultation: Immediate surgical consultation should be obtained in patients whose presentation of abdominal pain involves hemodynamic instability and/or a rigid abdomen. It is important to consider which specialty to consult based on the likely diagnosis. For instance, a ruptured AAA will be managed by vascular surgery, a perforated viscus by general surgery, testicular torsion by urology, and a ruptured ectopic pregnancy by OB/GYN. Nonsurgical consultation such as gastroenterology for a GI bleed or the medical ICU for diabetic ketoacidosis may also be necessary.

Outpatient Follow-up: Approximately 25% of patients presenting to the emergency department with abdominal pain ultimately receive the diagnosis of “nonspecific abdominal pain,” and follow-up is an essential part of their disposition plan. Of these patients, 30-hour follow-up can yield a difference in diagnosis or treatment in up to 20%. In addition to expedited outpatient follow-up, many patients presenting with nonspecific abdominal pain may benefit from outpatient specialty follow-up for further, non-emergent testing.

Of these patients, 30-hour follow-up can yield a difference in diagnosis or treatment in up to 20%. In addition to expedited outpatient follow-up, many patients presenting with nonspecific abdominal pain may benefit from outpatient specialty follow-up for further, non-emergent testing.

Case Resolution: The patient is given morphine and ondansetron with good resolution in her symptoms. Her EKG is normal. A bedside ultrasound demonstrates gallstones with a normal-appearing gallbladder without wall thickening, pericholecystic fluid, or dilated common bile duct. Her liver function tests, white blood cell count, and lipase are normal. Her urine pregnancy test and urine analysis are similarly normal. After an hour of observation she tolerates food without significant pain and her abdominal examination is benign. She is discharged home with strict return precautions and an outpatient referral to general surgery to discuss elective cholecystectomy for symptomatic cholelithiasis.

Boendermaker AE, Coolsma CW, Emous M, Ter Avest E. Efficacy of scheduled return visits for emergency department patients with non-specific abdominal pain. Emerg Med J. 2018 Aug;35(8):499-506.

Cinar O, Jay L, Fosnocht D, Carey J, Rogers L, Carey A, Horne B, Madsen T. Longitudinal trends in the treatment of abdominal pain in an academic emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2013 Sep;45(3):324-31.

Medford-Davis L, Park E, Shlamovitz G, Suliburk J, Meyer An, Singh H. Diagnostic errors related to acute abdominal pain in the emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2016 Apr;33(4):253-9.

O’Brien MC, In: Tintinalli JE, Stapczynski J, Ma O, Yealy DM, Meckler GD, Cline DM. eds. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide, 8e New York, NY: McGraw-Hill

Patterson BW, Venkatesh AK, AlKhawam L, Pang PS. Abdominal Computed Tomography Utilization and 30-day Revisitation in Emergency Department Patients Presenting With Abdominal Pain. Acad Emerg Med. 2015 Jul;22(7):803-10.

2015 Jul;22(7):803-10.

From time to time, the ATV will be naughty and behave differently than you would like. Nothing beautiful lasts forever, right?

One of the most common problems you may encounter is the ATV suddenly pulling to the left or right.

If you are lucky, your problem may have a simple solution)

Let's take a look at some of the most common reasons why an ATV can pull to the side, and of course, here we will talk about how to get rid of these problems.

The most common problem that causes the ATV to pull to one side is the difference in rolling resistance due to different tire pressures. Also, the problem may be associated with natural wear or damage to various components of the chassis of the ATV and, as a result, a violation of the angle of the wheels.

So how do you determine what is causing problems when riding an ATV?

As you probably already understood, there can be several reasons.

To understand why an ATV wants to pull off the road and dive into a ditch when you really don't want to, you need to do a number of checks.

Although I don't have exact statistics to tell you which malfunction occurs most often, I still recommend that you start with what is easiest to check and fix before spending time and money on more unusual and potentially more complex searches.

In my experience, the most common cause, and by far the easiest problem to check and fix, is uneven ATV tire pressures.

Let's look at what happens when ATV tires have different pressures.

A flat tire has a larger area of contact with the road surface than a normally inflated wheel, as a result of which the friction force, and hence the rolling resistance force, applied to such a wheel will be higher. The wheel will roll more slowly. The opposite wheel will run ahead and try to turn the ATV around the slow wheel. That is, if the ATV pulls, for example, to the left side, most likely, the fact is that the left wheel is lowered.

To solve this problem, you need to equalize the air pressure in the ATV tires. It is best to refer to the operating instructions, which must indicate the required air pressure in the wheels recommended by the manufacturer. The pressure in the wheels installed on the same axle of the ATV must be the same.

At the same time, you should be aware that due to the design features and weight distribution of the ATV, the tire pressure on the front and rear axles may differ.

Check with a good tire pressure sensor.

Most manufacturers complete the ATVs with a set of tools and a sensor for checking air pressure in wheels, such as ATVs Yacota SELA 200 , Yacota SELA 150 , Yacota Cabo 200035, Yacota Cabo 20035, , , 9003 MOTAX 200 , MOTAX GRIZLIK and MOTAX RAPTOR .

ATVs MOTAX and YACOTA have these sensors in the standard tool kit. If there is no such device in your kit, I recommend that you definitely purchase it. A very slight difference in air pressure in the tires may well be the reason that the ATV pulls to the side when driving in a straight line.

If there is no such device in your kit, I recommend that you definitely purchase it. A very slight difference in air pressure in the tires may well be the reason that the ATV pulls to the side when driving in a straight line.

The air pressure should be checked in both front and rear tires. True, uneven pressure in the rear tires, most likely, will not be the reason for the withdrawal of the ATV from a straight path. Different pressure in the rear tires can provoke another malfunction - premature wear of the rear differential, due to the increased load on it. But this is a story for a separate review.

I always keep this inexpensive instrument in my toolbox, its accuracy is good enough to use.

Also make sure that the maximum tire pressure is not exceeded.

Over time, ATV wheels can wear differently, resulting in the diameter of one wheel being different from the diameter of another wheel. This can also cause the ATV to pull to the side.

To check if the front wheel diameters are the same, you can do a simple check: place the ATV on a flat surface and use chalk to mark the sidewall of each front tire at the lowest point.

Wheels must be pointing straight ahead, gear lever in neutral position. Roll the ATV forward until one of the wheels has made two or three revolutions and the mark you just made is back to the very bottom, to its original position. Look at the mark on the opposite tire. Ideally, it should also be at the very bottom. If this is not the case, the wheel circumferences do not match.

If the reason for the ATV pulling to the side lies in the difference in wheel circumference, then when driving to the right, the right tire should have a smaller circumference, and when driving to the left, the left one.

Wheel circumference can vary not only due to uneven wear, but also due to air pressure differences in the tires.

The wheel is like a balloon, the higher the pressure, the larger its diameter and vice versa.

For this operation, you need to lift the ATV, place it steadily on the supports so that all the wheels are in a suspended state.

It is very convenient to use the bike racks to lift the ATV. If you do not have them yet, and you plan to service the ATV yourself, I recommend purchasing them. They are relatively inexpensive. Tackles will greatly simplify the ATV maintenance process.

Check that there is no excessive play in the ATV suspension and steering joints. Start with the tie rods and steering rack. This operation is more convenient to carry out with an assistant. Have an assistant move the ATV handlebars to the right and left, often and with a small range of motion. And you, in turn, keep your hand on the swivel, which are subject to verification. Check the steering tips and tie rods one by one. You will feel the excess play in the hinge with your hand. If the ATV steering wheel has excessive play, but the tie rod and steering tip are in order, then the steering rack itself or the steering shaft bushing may have play, which can also be checked by hand. The steering column bushing usually wears out over time. The same goes for the ball joints on the tie rods.

The same goes for the ball joints on the tie rods.

Tighten any loose bolts and replace worn parts. Worn parts can break soon, so replacing them won't be a waste of money, even if their wear isn't the reason your ATV pulls to the side.

In addition, the wheel bearings must be checked for excessive play.

To do this, have a helper grab the top and bottom of the wheel and shake it while you check for play in the ball joints and wheel bearings.

Check how easy the wheels turn. The wheels should rotate freely, without noise and crackling. The presence of noise indicates wear on the hub bearing. And the tight running of the wheel is about bearing wear or souring of the brake pads. As we said, if one of the ATV's wheels is spinning at a slower speed than the other wheel, the ATV will pull towards the slow wheel.

If necessary, replace the bearings and service the front brake calipers. Sometimes the caliper is easy enough to clean, and sometimes you can’t do without replacing the brake cylinders or the caliper bracket itself.

Complete the work with suspension lubrication. The chassis of ATVs of the brands YACOTA , MOTAX , AVANTIS is equipped with special grease fittings through which you can easily lubricate the desired suspension unit. We have already told, in one of the reviews, using the example of a gasoline 125 cc ATV MOTAX T-REX , about the features of maintenance of the ATV suspension. Regular maintenance of your ATV will definitely prolong its life.

Control check three: check the running gear for geometry violations.

If you use the ATV for active riding or sports, then it is possible that you have bent some part of the suspension on the next jump. ATV front suspension A-arms are especially prone to damage if you hit a stump or rock while riding. "Fast-growing" trees suddenly appearing in front of the ATV as you drive, a common story!)

A-arms are designed to absorb heavy suspension shock and, through their integrity, retain more expensive and hard-to-find ATV parts that are more difficult, more expensive or even impossible to repair, for example, an ATV frame. It is not always easy to see if the suspension arm is bent or not. It happens that the levers do not have a symmetrical shape, because the ATV suspension was originally designed this way by the manufacturer.

It is not always easy to see if the suspension arm is bent or not. It happens that the levers do not have a symmetrical shape, because the ATV suspension was originally designed this way by the manufacturer.

Compare the distance between the axles of the front and rear wheels of the ATV on the right and left sides. If there is a difference, then one of the suspension arms is most likely damaged.

The camber and toe angle can be adjusted by eye yourself, but it is better to contact specialists who have the necessary measuring equipment and data on the required wheel alignment values.

I hope you find this article useful.

For all questions related to the purchase, selection and repair of ATVs and other equipment presented in the VEZDEHOD online store, please contact our consultants. We will be happy to help you choose a new ATV according to the specified parameters and solve any technical issue related to the malfunction of already purchased equipment.

The 21st century can be safely called office. Especially the last 5 years. More and more remote work appears, more and more specialties related to the IT sphere appear. And this means that people need not only more pants to wipe them on the office chair, but also more active forms of recreation, so as not to grow roots in the floor of the office or their own home. One of the most actively gaining popularity types of recreation is quad biking. It is good because it will suit absolutely everyone: both lovers of easy walks in the forest or the coast, and those who crave thrills in impenetrable mountains, deserted fields and swamps.

Especially the last 5 years. More and more remote work appears, more and more specialties related to the IT sphere appear. And this means that people need not only more pants to wipe them on the office chair, but also more active forms of recreation, so as not to grow roots in the floor of the office or their own home. One of the most actively gaining popularity types of recreation is quad biking. It is good because it will suit absolutely everyone: both lovers of easy walks in the forest or the coast, and those who crave thrills in impenetrable mountains, deserted fields and swamps.

If this is going to be your first ATV, then you can start with simple budget models, since you still won’t feel the difference now. And in order to spend a minimum of time on the purchase, keep five important tips for buying a quadric without a headache.

This is important to decide well before buying. If you have decided to ride this frisky iron pony for the first time, then it is preferable to opt for a new model.

First, the dealer always gives a guarantee. This will save you from problems in the event of a breakdown - you just drive the ATV to the service and experienced specialists will fix all the problems.

Secondly, an inexperienced ATV rider will not be able to identify serious flaws or recognize technique after drowning. Water is not the best companion for any transport and, in most cases, it is necessary to change the engine or transmission, and this is exactly half the price of the entire “pony”.

Thirdly, when you ride a certain amount of time and understand what you lack in a quadric and decide to buy a more powerful or comfortable one, it will be much easier to sell your predecessor. Equipment that had only one owner flies under the hammer much faster than the one that was in the hands of two or three people.

ATV . Single / double without a cab with a motorcycle landing (the passenger sits behind the driver) and a “bicycle” steering wheel. Such vehicles have a shorter wheelbase, which means better geometric cross-country ability and compact size. This makes the ATV more maneuverable, resistant to rollover. In addition, due to the mass of no more than 450 kg, it falls into the mud less.

Such vehicles have a shorter wheelbase, which means better geometric cross-country ability and compact size. This makes the ATV more maneuverable, resistant to rollover. In addition, due to the mass of no more than 450 kg, it falls into the mud less.

SSV . Two- / four-seater with a cabin similar to a car. Inside: there are seats, a round steering wheel, a wide dashboard. The long wheelbase of such all-terrain vehicles increases stability and controllability at high speeds, the load capacity is much higher - up to 400 kg. But such quads will not be so maneuverable and are more like a full-fledged off-road car.

The choice depends on your goal: whether it will be solo “rides” or whether you are ready to take on board passengers for joint entertainment.

It is obvious that the leaders in the production of equipment are the Japanese. Brilliant Asians have thought through and invented literally everything. Moreover, it also works great! Therefore, we recommend that you look at Yamaha, Honda. These are reliable and durable ATVs that are not scary to buy even with hands. Used options can be easily chosen among the options of 2002-2007 release years.

Moreover, it also works great! Therefore, we recommend that you look at Yamaha, Honda. These are reliable and durable ATVs that are not scary to buy even with hands. Used options can be easily chosen among the options of 2002-2007 release years.

Canadian BRP technology has become very popular in recent years. Over the 70 years of their existence, they have learned to make vehicles equipped with literally everything. And each new model is becoming more and more perfect vehicle, capable of surviving in literally any conditions.

American Polaris is also a quality, hard-working brand. The engines have high traction performance and a degree of safety.

In recent years, many Chinese manufacturers have appeared on the market, attracting with their price. Despite the fact that China is advancing and improving quite quickly in the production of any goods, nevertheless, it is still inferior in quality to top brands. Parts for such ATVs are cheap and affordable, but, most likely, the need for them will arise more often than after buying the same Bierpie.

When choosing a good ATV, pay attention to the main performance characteristics, namely:

Engine capacity. For hunting, fishing, sports, driving on a dirt road, 150-230 cm3 will be enough. To dive into extreme tourism, you should choose a powerful engine of 350-689 cm3.

Power. For light riding or training, 13-15 hp will be enough for you. If the plans are full-fledged trips through the endless impassability of our Motherland (and we mean mountains and forests, not cities in the middle zone), then you should put a pony with a capacity of up to 45 horsepower in a stall. It is horse, not pony.

Transmission. Mechanical - suitable for moving on more or less flat roads, as it requires attention when switching gears.

CVT - suitable for hunting or fishing, where in manual mode it is necessary to switch gears only in loose areas or when encountering obstacles.

Automatic gearbox. She controls the speeds depending on the engine speed and road conditions. You can focus entirely on the route or immerse yourself in the performance of a sports stunt.

She controls the speeds depending on the engine speed and road conditions. You can focus entirely on the route or immerse yourself in the performance of a sports stunt.

Cooling system. You should not allow the engine to overheat, which means you need to choose the right cooling system for your needs. The air type is suitable for lighter fishing or hunting trips, for example. If everything is hardcore for you, then it is better to choose a fluid system that will provide the quadric with more heat transfer, and you will have peace of mind during extreme recreation.

Well, the last but the main advice. Before choosing an ATV, think carefully for what purpose you need it: sports, walking or extreme riding. It depends on the amount you invest. Better yet, first rent an ATV a couple of times and understand whether you will ride it from time to time or whether you claim to be a quadro-maniac. In this case, of course, it is worth buying your own transport, but you also need to approach the choice more carefully - you will need more than five tips.

And if you do not want to delve into the intricacies of choice and want to immediately get a good ATV that meets your needs, then you can always turn to specially trained people who, for a fee, are engaged in the selection of auto and motorcycle transport. As a rule, these are well-versed people who know the design of an ATV, have information about new products and have all the necessary technical means that can identify all the shortcomings of a vending instance.

But whatever your goal when buying an ATV, be prepared to shell out a tidy sum for the transport itself, accessories, equipment and storage space. If you have a small one-car garage, then it is worth considering an alternative shelter for the ATV, where it will live quietly and not interfere with you during your daily use of the car.

A garage 3-4 meters long is suitable for an ATV. As with any vehicle, the roof and walls must be airtight. In order for it to serve you for more than one year, you should pay attention to iron garages. They are not only durable, the formation of mold and guests in the face of rodents is excluded. The SKOGGY metal garage is designed just for storing equipment such as an ATV. It is made of the professional sheets processed from corrosion. The roof does not leak, the installed drains remove all the consequences of precipitation, just do not forget to periodically clean it from leaves, sticks, birch buds and other debris.

They are not only durable, the formation of mold and guests in the face of rodents is excluded. The SKOGGY metal garage is designed just for storing equipment such as an ATV. It is made of the professional sheets processed from corrosion. The roof does not leak, the installed drains remove all the consequences of precipitation, just do not forget to periodically clean it from leaves, sticks, birch buds and other debris.

The collapsible design will allow you to move the garage from place to place, unless of course there is a need for this. You never know, suddenly you decide to move on your ATV to another house. You can take the garage with you. Yes, and if you are planning a rearrangement on your site, a couple of hours - and the garage is dismantled. We rested, decided on a new place, another hour or two - and the garage for the ATV is already in a new place.

You can choose a collapsible garage design from profiled sheets, or you can choose a frame one. In the second case, the garage is also collapsible, but the frame is assembled before sheathing with corrugated board. Gates can be made ordinary swing or use roller shutters. It is possible to install a gate in any part of the garage.

And for connoisseurs of the coolness of not only an ATV, but also its keeper, you can apply the most brutal print.