❚ The products mentioned in this article are selected or reviewed independently by our journalists. When you buy through links on our site we may earn an affiliate commission, but this never influences our opinion.

It might be a basic thing, but being able to pump up your bike’s tyres is an essential skill for any cyclist.

A lot of you will already know how to do this, but for those who don’t, the different valve types, pumps and, more importantly, what pressure to pump your tyre can be a bit overwhelming. Let us guide you through the process.

Pneumatic tyres were invented to get over the bone-jarring ‘ride-quality’ of solid wheels.

The air inside acts as a spring, providing suspension for you and allowing the tyre to conform to the terrain providing better traction and grip.

Pumping up your tyres is a quick job that can easily improve your enjoyment while riding. Running the wrong tyre pressure will negatively affect the way that your bike rides and can also make your bike more prone to punctures.

If you’ve never repaired a puncture before, you might not have considered how your tyres hold air inside.

The vast majority of bikes will use an inner tube. This is a doughnut shaped airtight tube that sits inside the tyre, with a valve for pumping it up that you see on the outside.

The tyre, when inflated by the tube, is what grips the ground and provides protection from punctures.

You may have heard of tubeless tyres, which forgo a tube and use a special rim and tyre to seal air without the need for a tube. These usually require tubeless sealant inside, which is a liquid that plugs any points where air is escaping.

Tubeless tyres are more commonly found in mountain biking, but the technology is migrating to road bikes.

The tubeless sealant also plugs punctures, and no tube means a much lower risk of pinch flats – that’s when your inner tube is pinched by the rim, causing a puncture. Tubeless tyres can, therefore, be run at lower pressures than those with an inner tube setup, for improved comfort, speed and traction.

Tubeless tyres can, therefore, be run at lower pressures than those with an inner tube setup, for improved comfort, speed and traction.

At the very high end, you also get tubular tyres. This is essentially a tyre with the tube sewn into it, but they are rarely seen or used outside of professional racing.

Inflating your tyres to the correct pressure is an essential part of bike maintenance.Oli Woodman / Immediate Media

Running your tyres at either too high or too low a pressure can be potentially dangerous, as well as negatively impact the handling of your bike.

We’ll discuss later what the correct pressure is, but for the moment let’s look at possible problems.

An under-inflated tyre will rob your efficiency and leave you susceptible to annoying punctures.Oli Woodman / Immediate Media

If you run your tyres at too low a pressure, the tyre can wear prematurely. Excessive flexing in the sidewall can lead to the casing cracking and the tyre becoming fragile. This could eventually lead to a blowout.

This could eventually lead to a blowout.

Excessively low pressures also increase your susceptibility to punctures and may even result in your tyres literally rolling off the rim if you corner at speed (the pressure inside is what holds your tyre on the rim).

Damage can also be caused if the tyre deflects all the way down to the rim. This can result in dents or cracking, potentially compromising your wheel and resulting in an expensive replacement.

Conversely, running too high a pressure could result in your tyre blowing off the rim with explosive consequences. That pressure can also squeeze the wheel because if it’s too high the compressive force on the wheel can be too high.

In terms of handling, a low pressure can result in compromised handling with the tyre squirming under load. Your bike will feel difficult to control, slow and sluggish.

On the other hand, too high pressure can result in reduced grip and a harsh ride, leading to fatigue and in turn impacting handling.

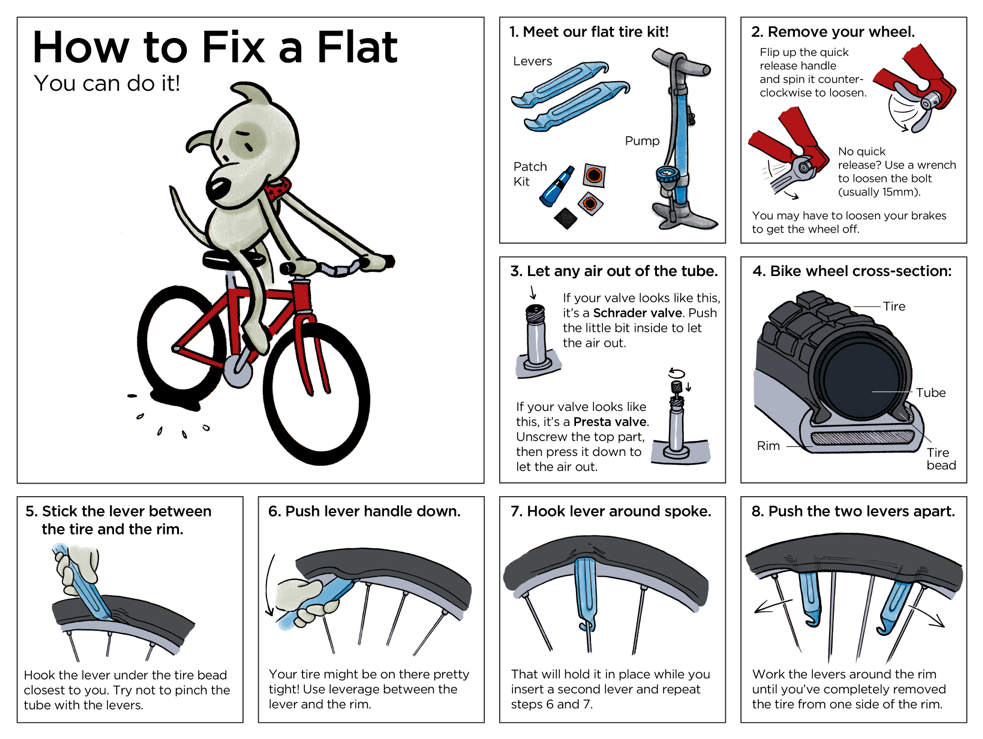

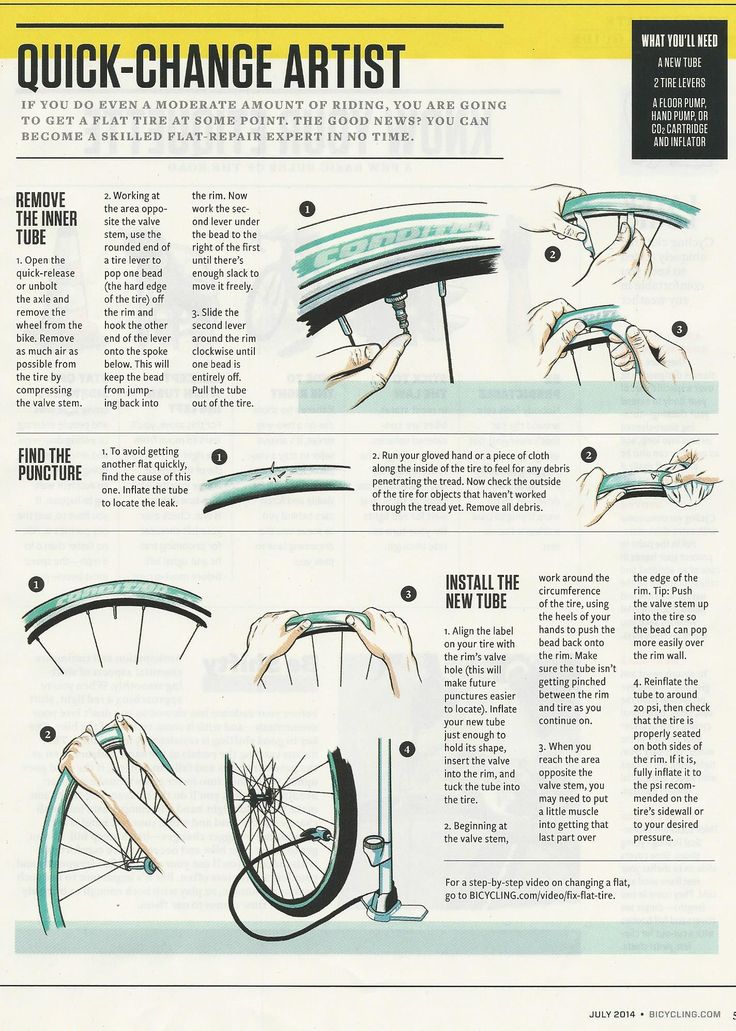

There are two likely reasons why your tyre is flat. Either you have a puncture or your tyre has just deflated over time.

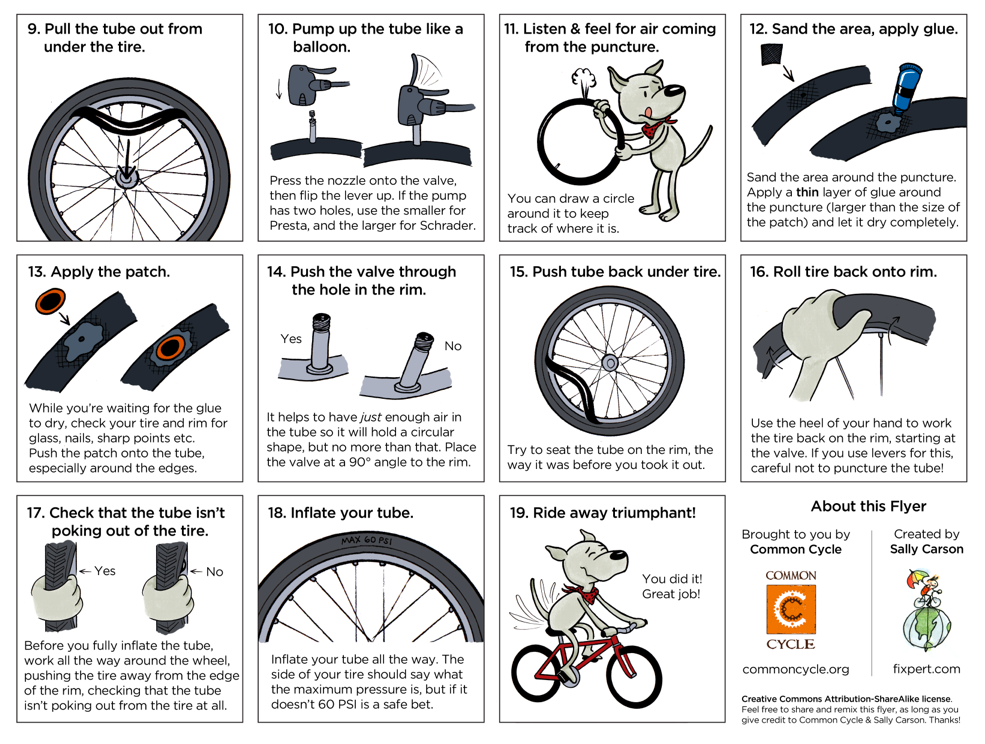

If you have a puncture, we’ve put together a comprehensive guide on how to fix a puncture.

Glueless patches are great for a quick fix, while a more traditional kit is a versatile option when you have a bit more time.

All tyre systems will leak air slowly because tubes aren’t completely airtight. For example, standard butyl tubes hold air fairly well compared to lightweight latex tubes, which leak comparatively quicker. Even tubeless setups will slowly leak air.

Old tubes will leak more air than new ones, so if yours haven’t been replaced in a while they may be worth looking at. Less likely, but also a possibility (especially on older tubes), is that the valve is no longer sealing properly.

The best way to check what’s going on is to try pumping up the tyre. If it holds air then there’s likely nothing more you need to do. If it doesn’t, then you likely have a puncture.

If it doesn’t, then you likely have a puncture.

If it leaks air slowly overnight, either you have a slow puncture or simply an old tube that needs replacing.

The first thing you’ll need to know before pumping up your tyre is what valve type is fitted.

The valve is the key part that keeps air in the tyre, but also lets you inflate (or deflate) the tyre.

The Schrader valve is also used for car tyres.Oli Woodman / Immediate Media

Schrader valves are more common on lower-end bikes and, in the past, mountain bikes. The same valves are used on car tyres.

The valve assembly is a hollow tube with a sprung valve that closes automatically and screws into the external body. A pin extends up from the valve and is usually flush with the end of the outer tube. This pin can be depressed to let air out.

The dust cap on Schrader valves is an important part of the design that can help fully seal the valve if it is not completely air-tight. It essentially provides a secondary ‘backup’ seal.

It essentially provides a secondary ‘backup’ seal.

The sprung design of the valve is a little susceptible to contamination from dirt or grit so it’s important to protect it too.

Presta valves such as this one are longer and narrower than the Schrader type valve.Oli Woodman / Immediate Media

You will only find Presta valves on bicycles.

They originated on road bikes where the narrower valve (6mm vs 8mm for a Schrader) meant a smaller valve hole (typically the weakest part of a rim) on narrow road wheels.

Nowadays they are seen on both mountain bikes and road bikes. Rather than use a spring, the valve is secured with a nut that holds it closed, though the valve itself is sealed ‘automatically’ when pressure inside the tyre pushes it shut.

With a Schrader valve, you can simply press the pin to release air, but with a Presta valve you first have to unscrew the little locknut. Don’t worry about the nut coming off the end of the valve body because the threads are peened to stop that happening.

There seems to be a myth that Presta valves deal with high pressures better – this probably isn’t true considering there are Schrader valves that can withstand many hundreds of psi (way more than you’ll ever need in your tyre).

Presta valves are definitely a little more delicate than Schrader valves, though. It’s quite easy to knock the threaded internal valve body and bend or break it, so a bit more care needs to be taken. However, valve cores are easily replaceable with standard tools.

In comparison, on Schrader valves, this requires a proprietary tool.

Presta valves may come with a lockring that secures the valve body against the rim. This can make them a little easier to inflate. The dust cap is not essential to seal it, but helps keep the valve clean.

The only other type of valve you may come across is a Dunlop (also known as Woods) valve. This has a similar base diameter to a Schrader valve, but can be inflated with the same pump fitting as a Presta valve.

These are very popular on town/upright bikes in Europe and elsewhere in the world, but you’re very unlikely to come across one in the UK or in the US.

A tubeless valve can be difficult to distinguish from a regular Presta valve.Oli Woodman / Immediate Media

Valves for tubeless setups are attached directly to the rim, rather than being part of an inner tube.

More often than not, they are Presta-type, but Schrader ones do exist.

Oli Woodman / Immediate Media

If you’ve got a Schrader type valve, such as the one shown above, then the first thing you need to do is remove the dust cap (if there is one in place).

Oli Woodman / Immediate Media

Simply unscrew the cap anticlockwise to reveal the valve.

Oli Woodman / Immediate Media

Now attach the head of your pump.

Oli Woodman / Immediate Media

Inflate the tyre to a value between the minimum and maximum stated on the tyre sidewall and remove the pump. You’re done!

You’re done!

Oli Woodman / Immediate Media

If your bicycle has a Presta type valve such as this one then you will first have to remove the plastic valve cap (if fitted).

Oli Woodman / Immediate Media

The plastic cap will reveal another threaded cap to the valve.

Oli Woodman / Immediate Media

Unscrew the thread but be careful to not damage it in the process.

Oli Woodman / Immediate Media

Now attach the head of your chosen pump to the open valve and inflate the tyre to a pressure that’s between the minimum and maximum stated on the tyre’s sidewall.

Inflate the tyre to the desired pressure and remove the pump.

Oli Woodman / Immediate Media

Finally, close the valve by screwing it clockwise and reinstall the plastic valve cap.

If you have a tubeless setup, or tubes setup with sealant inside, then it’s worth taking a few extra steps to avoid gunking up your pump.

Turn the wheels so the valves are at the bottom and leave for a few minutes so any sealant can drain out.

Turn the wheels so the valves are at the top and pump up your tyres. The same goes when deflating tyres to prevent goop spraying everywhere.

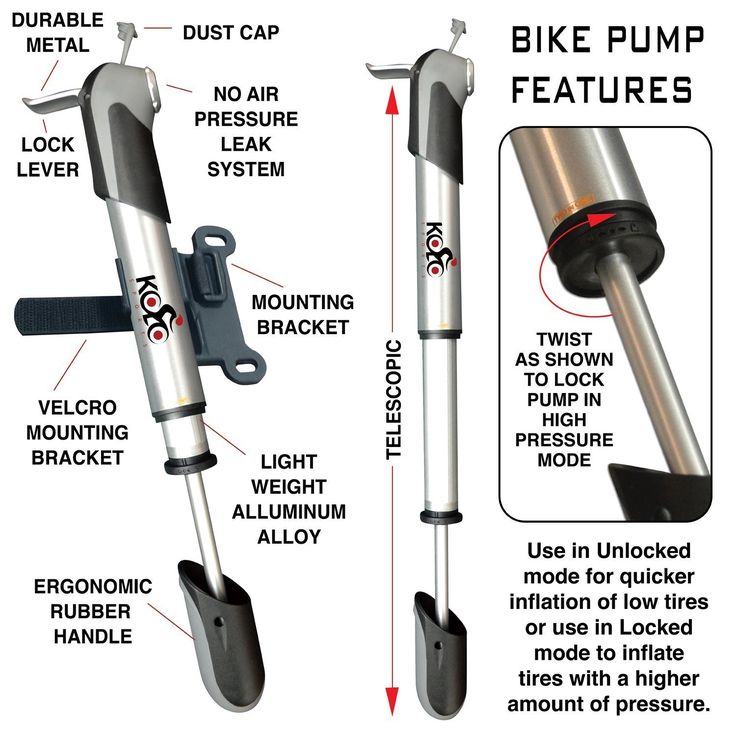

We’d say that, if you can only own just one type of pump, get a track pump for home use because it’s efficient, quick and easy to use.

However, there’s no doubt that having an additional mini-pump for when you’re out on the road is rather useful – otherwise you risk being stranded at the roadside in the event of getting a puncture.

We’ve already got a guide on choosing the best bike pump for your needs, but here a few recommendations for you to consider.

The sky’s the limit with track pumps. They basically all do the same job, some with a more premium feel than others.

From a budget Park Tool PFP8 to the absurdly expensive Silca Pista Plus, you’ll be able to find something that suits your needs.

Mini pumps work but are a lot more frustrating to use. Again, there are lots of options available from mini track-style pumps to tiny pumps that will fit in a jersey pocket. We tend to prefer mini pumps with a hose because that reduces stress (and potential damage) on the valve.

Two of our favourites have been the Truflo TIO Road and the Lezyne Micro Floor Drive HP.

One other possibility for your inflation needs is a CO2 inflator. These use compressed carbon dioxide in a small cartridge to inflate or top up a tyre really quickly. Not something you would want to use on a regular basis, but perfect for an emergency repair.

The first thing to do is to attach your pump to the valve.

Remove the valve cap, and regardless of valve type, we find it’s good to release just a little hiss of air to ensure the valve isn’t stuck and opens and closes cleanly. Either thread-on the chuck or push it on and lock it.

Either thread-on the chuck or push it on and lock it.

If your tyre is completely flat it may initially be a bit of a struggle to fit the chuck because the valve has a tendency to push back into the rim. Simply hold the valve from behind by pushing on the outside of the tyre so that you can lock the chuck on properly.

The lockring on Presta valves (if fitted) can also help, preventing the valve from disappearing by holding it in place for you.

The connection to the valve should be air-tight. A little escaping air is normal when attaching the pump, but shouldn’t continue for long. If it does, remove and reattach the chuck. If it continues to be a problem it may be worth checking the rubber seal in the chuck to see if it is worn out and needs replacing.

Remember to be gentle with the valves – they’re delicate. That’s especially the case if you’re using a mini pump without a hose.

Make sure to brace the pump with your hand wrapped around the spokes or tyre to avoid transferring too much of the pumping force to the valve, which could lead to damage.

When you start pumping make sure to use the full stroke of the pump. You’ll find that the majority of the stroke is taken up compressing the air to the point where it will then be pushed into the tyre.

If you don’t use the whole length of the pump, the air won’t be pushed out of the bottom – you need to generate overpressure in order to move the air from the pump to the tyre. Instead, you’ll just end up with the shaft bobbing around doing nothing.

With a track pump, don’t just use your arms, use your body weight for the downstroke and pumping will become a lot easier.

You may sometimes find that the pump doesn’t seem to hold pressure, especially when inflating the tyre from completely flat. This may especially be the case with an older pump where seals may be slightly sticky.

We find it helps to pump vigorously initially, to generate enough back-pressure (i.e. pushing back from the tyre side) in the system to ensure that valves are actuated properly and seal up, in turn inflating the tyre. Keep on going until you get the right pressure.

Keep on going until you get the right pressure.

When removing the chuck from the valve there is usually an audible hiss of air being lost. This is usually from the pump rather than the valve side. Pressured air in the hose and chuck is just escaping.

A pump gets the air in your tyre. The operating principle is simple; you increase the pressure inside the pump until it exceeds that inside the tyre. This ‘overpressure’ forces air into the tyre, increasing its pressure too.

A pump is just a manually actuated piston. On a pump’s downstroke, a check valve (allows air-flow in one direction) seals the piston chamber, resulting in air being pressurised as the pump is compressed. That pressure increases until it exceeds that inside the tyre.

At this point, a second one-way valve will allow air to flow from the pressurised pump chamber into the tyre. You extend the pump again, the check valve opens to refill the chamber with air and you repeat the process.

To prevent the pressure in the tyre leaking back out, the second check valve at the base of the pump closes. If it wasn’t there, the pump would just shoot open again.

Presta valves will close automatically, but the sprung Schrader valves are usually held open by a pin in the pump valve attachment (this means you don’t need any extra effort when pumping to overcome the pressure exerted by the spring.)

The head of the pump is also known as the chuck.Oliver Woodman / Immediate Media

The chuck is the part that attaches the pump to the valve and forms an airtight seal over the valve. One of two designs exist: threaded or push-on with a locking lever. Most pumps nowadays are also adaptable to either Schrader or Presta valves.

They will either feature two different attachment points or an adjustable chuck that can be changed to suit both types.

For larger pumps (and many mini-pumps too) the chuck is often on a hose, preventing your pumping force from damaging the valve.

Pumps will often include a pressure gauge to check the pressure inside your tyre.

The right tyre pressure is perhaps one of the most contentious subjects, but there are definitely a few guidelines that you can use.

As a general rule, your tyre should be solid enough to prevent the tyre deflecting all the way to the rim, though compliant enough to provide some suspension – after all, the beauty of a pneumatic tyre is that you don’t have to have a bone-jarringly hard ride.

Most tyres will have a minimum and maximum pressure rating printed on the side. It’s advisable not to go under or over those limits because manufacturers have specified them for a reason. Of course, that means there’s still a lot of room to play with pressure and what works for you.

For mountain bikes the problem is relatively easier, with the usual aim being to improve traction, cornering and shock absorption.

As a general rule, riders try to run as low a pressure as possible without having it so soft that the tyre squirms under cornering load or deflects enough for damage to occur to the rim.

For road bikes it becomes a little more complicated because along with traction and comfort, rolling resistance (how efficiently a tyre rolls) is a major consideration as well.

Contrary to what many assume, the new school of thought seems to suggest that harder is not necessarily faster.

On all but the smoothest of surfaces, a hard tyre will not have as much suspension, and instead of the tyre being able to deflect and conform to irregularities – keeping the bike moving forward – you will get bounced around.

On all but the flattest of surfaces softer tyre pressures can provide more comfort and be more efficient.

A tyre pressure drop chart.Frank Berto (Bicycle Quarterly)

The most comprehensive research into this was underatken by Frank Berto, who put together a tyre pressure inflation chart.

This testing determined that a 20 per cent tyre drop (the amount the tyre compresses when load is applied, measured by the height from the ground to the rim) was the optimum balance.

Incidentally, some manufacturers recommend a similar level of tyre drop, though the figure is open to some debate.

This value does provide a good starting point to experiment with tyre pressures. The chart looks at individual wheel load – i.e. your and your bike’s weight on each wheel (40 per cent front / 60 per cent rear is a good starting point) – and calculates the pressure for each accordingly.

You need not always get your pump/gauge out to check for tyre pressure.BikeRadar / Immediate Media

It’s a good idea to check your tyres before each ride. Usually, that just involves giving them a squeeze by hand to check the pressure.

No, it’s not super accurate, but you’ll quickly get a feel for the pressure in your tyres and be able to tell whether they need pumping up or not.

If you start to get really nerdy about it, you may end up investing in a pressure gauge, which can read the pressures in your tyres very accurately.

That’s especially helpful for mountain bikes where a few psi can make a large difference to handling and grip, but equally applicable on a road bike to find the exact pressure that works for you.

BikeRadar provides the world's best riding advice. We're here to help you get the most out of your time on the bike, whether you're a road rider, mountain biker, gravel rider, cycle commuter or anything in between. You can expect the latest news and features, in-depth reviews from our expert team of testers, impartial buying advice, how-to tips and plenty more.

Skip to content

All bike tires slowly leak air every day. Even if you’re an occasional rider, and you only take your bike down from the bike rack once a week, the tire pressure will still decrease. Before you ride, you should always check your tires’ PSI and, if needed, inflate them with a floor bike pump or a handheld pump.

Before you ride, you should always check your tires’ PSI and, if needed, inflate them with a floor bike pump or a handheld pump.

On the sidewalls of your tires, you’ll see the manufacturer’s recommended pressure range for PSI (pounds per square inch). Different bike tires have different ranges, and narrow tires need more pressure than wide tires. The recommended PSI for different tires are:

Experienced cyclists can often estimate whether their tires need to be pumped by pinching the tire between their thumb and forefinger. The more accurate way of knowing when your tire should be pumped is by measuring its pressure with a pressure gauge; if the air pressure is measured below the recommended PSI, it’s time to pump.

First pump your bike tire to the middle of the range for the recommended PSI. You also need to take your body weight into account. Tires that bear a heavier rider need more PSI. Weather conditions and terrain also affect how a bike rides, so you’ll need to experiment with different PSIs to feel what’s most comfortable to you.

Tires that bear a heavier rider need more PSI. Weather conditions and terrain also affect how a bike rides, so you’ll need to experiment with different PSIs to feel what’s most comfortable to you.

A Schrader valve is the type of valve you’ll find on car tires, older bike tires and mountain bikes. It consists of a metal pin in the center of a threaded valve, and a rubber cap that’s screwed onto the valve. Most bike pumps like those we reviewed have a dual head to accommodate both Schrader and Presta valves or a single head with an adapter.

A Presta valve is found on road bikes and some mountain bikes. It’s a slender valve with a nut at the top that is loosened and tightened before and after inflation. Almost all new bike pumps have a head with openings for both Schrader and Presta valves, or they have an adapter for switching from Schrader to Presta, like one of our top picks, the Topeak – Road Morph G.

If you’re out riding and your tires need air, you could give them a quick inflate with a CO2 injector, like the one we reviewed. But if you don’t have a CO2 injector in your bag, and you forgot your mini pump, then you can pull into a gas station and inflate your tires there.

If you don’t have a pressure gauge, ask the station attendant for one. Inflate your tires to optimal pressure in short bursts; a gas-station air pump has very high pressure, and you run the risk of popping your tire.

A gas-station air pump will only fit a Schrader valve. But if your tires have Presta valves and you don’t have a Presta valve adapter, there’s still a way to inflate them.

Share this Review

Gene Gerrard, Writer

Gene has written about a wide variety of topics for too many years to count. He's been a professional chef, cooking-appliance demonstrator, playwright, director, editor of accountancy and bank-rating books, Houdini expert and dog lover (still is). When he's not writing for Your Best Digs, he's performing as a magician at the Magic Castle in Hollywood.

It's a good idea to check the tire pressure before every ride. For normal operation of tires, they must have a certain air pressure, which is important to maintain.

Many people know that there are now two types of nipples: the Schrader valve (car nipple) is thicker and cylindrical in shape, and the Presta valve (bike nipple) is thinner and has a locking nut at the end of it, which must be unscrewed to release air. That is, in the case of the Presta valve, you simply unscrew the nut, press on it with your finger, and the air comes out.

A typical mistake many beginners (and not only beginners, by the way) is that they try to inflate tires with a Presta valve with a regular car pump - naturally, no matter how hard you try, this will not work.

If you're not sure which pump to buy, check out our list of trusted bike pumps, or just ask your cycling friend for advice. In the case of pumps, everything is usually fair - as a rule, you get exactly what you paid for. If you spend a little more money, you'll have a more accurate gauge, a more reliable pump, and even easier tire inflation.

In the case of pumps, everything is usually fair - as a rule, you get exactly what you paid for. If you spend a little more money, you'll have a more accurate gauge, a more reliable pump, and even easier tire inflation.

First, unscrew the plastic cap that may be covering the nipple. Sometimes, by the way, caps are lost, and there is nothing to worry about. Then Presta faucet owners often forget this - loosen the little lock nut at the end of the nipple. Do not be afraid here - the nut will not go anywhere, so you can unscrew it right up to the stop. Click on it a couple of times to make sure it moves - when you press it, you should hear the rustle of air escaping. If you have a Schrader valve, you can skip this step.

Before you inflate a tire, look at the tire sidewalls - it should indicate the safe pressure range for this model. Typically road tires are rated between 80 and 130 psi, while mountain bike tires are rated at 25 and 50 psi, respectively. Hybrid bike tires are typically rated at 40 to 70 psi. The optimal pressure for you depends on your weight and riding style - here you need to experiment and see what you like best, or you can use our quick guide.

Typically road tires are rated between 80 and 130 psi, while mountain bike tires are rated at 25 and 50 psi, respectively. Hybrid bike tires are typically rated at 40 to 70 psi. The optimal pressure for you depends on your weight and riding style - here you need to experiment and see what you like best, or you can use our quick guide.

Connect the pump valve to the nipple. Some pumps have an adapter inside the valve that can be reversed to select Presta or Schrader valves, others will have a threaded head. The purpose of both systems is to hold the valve in place while inflating so that air enters the nipple rather than escaping.

If the air is coming out instead of going into the tire, the pump valve may need to be repositioned a bit. Try simply unplugging it from the nipple and plugging it back in.

While looking at the pressure gauge, inflate the tires to the correct pressure. Use hand and body strength when operating the pump. Squats are a good exercise for developing leg strength, but they are not the best for bike maintenance. Therefore, pump with your arms or even your abdominal muscles - the process can really feel like a little workout.

Use hand and body strength when operating the pump. Squats are a good exercise for developing leg strength, but they are not the best for bike maintenance. Therefore, pump with your arms or even your abdominal muscles - the process can really feel like a little workout.

Once the tires are inflated, turn the pump valve to disengage it from the valve and screw the lock nut back on if you have Presta valves. And then just pick up and ride!

Contents

Flat tires do not bode well for the cyclist. The situation must be resolved immediately, otherwise you will have to become a pedestrian for a while. What should be done? That's right, pump up the camera and calmly continue moving. Consider how to pump up a bicycle wheel with a pump, what subtleties are available when using an autocompressor, and whether it is possible to do without a pump.

Tire pressure is the main parameter that is responsible for the speed of movement, grip and safety of the cyclist. The average minimum indicator for bicycles is 2 atmospheres. For driving on asphalt, the recommended value is within 3.5 atm., For primers - 2.6 - 2.8 atm.

It is easy and simple to determine the pressure inside the bicycle chamber using a pressure gauge - separate or built into the pump:

Another method: feel around the tire with your fingers. If the rubber does not flex, then you can ride. It should be noted that this method will only give accurate results for thin slicks on road bikes and tires on city bikes.

Consequences of underinflated tyres:

On the contrary, an excess of air in the chambers threatens the following:

Maintaining the recommended pressure will eliminate all these shortcomings and allow you to get the most out of your trips and enjoy them. Below the values table depending on the weight of the cyclist:

| The mass of the cyclist, kg | atmospheres/PSI* |

| 50 | - 38 |

| 77 | 2.72 – 2.9/40 – 42.6 |

| 90 | 3.6/53 |

| 105 | 3.9/57.5 |

| 115 | 4.1/60 |

| 118 | 3. 2 - 3.4/47 - 50 2 - 3.4/47 - 50 |

In general, a bicycle pump is a necessary thing for every cyclist. With the help of this simple device, it will be possible to inflate the wheels on your own, and not roll your bike to a service or gas station.

Hand pumps are divided into two types: simple and with a recording device (pressure gauge). It is recommended to purchase the second option, however, if a separate pressure gauge was lying around in the cabinet, you can buy a cheaper pump.

Universal Hand Pump with Dial Gauge

For ease of pumping with a conventional hand pump, you can immediately count the number of air inlets until the optimum pressure is reached and then pump just like that, even without additional use of a pressure gauge.

How to properly inflate the chambers:

You can also inflate on an upside down bike or the wheel separately if the bike is being disassembled.

You can also inflate on an upside down bike or the wheel separately if the bike is being disassembled. Pressure tracking:

By the way, the latter will not be superfluous to do with a pressure gauge, since the pressure inside the pump may increase during pumping, but air does not enter the chamber (the valve is not completely closed) or exit through a hole in it.

Common bicycle nipples are automotive and Dunlop. For thin wheels, a Presta nipple with a valve is used. It requires cleanliness and accuracy in handling.

Presta thin nipple tubes fitted to road bikes and some hybrids

Fitted with a special low volume pump. A regular bike pump may not fit or you may need to use an adapter.

A regular bike pump may not fit or you may need to use an adapter.

Most bicycles have a "schrader" or car valve. The standard option allows you to inflate tires at gas stations and public bicycle pumps (of which there are only a few in our cities so far) directly.

How to inflate simple wheels with a car pump:

How to fill Presta with a compressor at a gas station:

In this case, it is very important to know exactly how many atmospheres it is necessary to let air into the chambers. With increasing pressure, it can quickly burst.

The last option left is Dunlop. It is identical in size to an automobile nipple, but in terms of design features it is similar to the French one (aka Presta). When inflating a wheel, you should follow the rules for a sports analogue.

Is it possible to inflate bicycle inner tubes without a pump? It is unlikely to reach the recommended pressure, since a regular supply of pressurized air is required, but you can reach the minimum values. Let's consider several methods of pumping the chambers, which can be resorted to without using a pump:

Vacuum cleaner. Many models are equipped with a blower mode, when switched to which air is blown out. A thin hose can be used to connect the wheel nipple. The result directly depends on the tightness of the connection between the hose and the nipple. Here you can use rubber pads, clamps and even rags.

A thin hose can be used to connect the wheel nipple. The result directly depends on the tightness of the connection between the hose and the nipple. Here you can use rubber pads, clamps and even rags.

Bottle pump. You will need two plastic bottles. One of them will serve as a cylinder, the other as a rod. Cut off the bottom of the first bottle and connect its neck through a thin hose to the chamber outlet. Next, insert the second bottle into it and with translational movements pump air through the cylinder into the hose. For tightness, grease the connection of the neck and the hose with sealant or lay a rubber pad. High pressure cannot be created, but it is possible to ride the N-th distance on a bicycle.

Bottle pump schematic: 1 - "rod", 2 - cylinder, 3 - cylinder neck, 4 - hose

The third way is to remove the nipple and inflate like a balloon. The method is fraught with difficulties in its removal and installation in its rightful place.