Did you know entry-level tire construction engineers, compounders and designers aren’t allowed to touch a new tire for a year or two? That’s because tire design and development isn’t part of any college curriculum. The making of a competent tire engineer isn’t the job of a college professor. That task belongs to veteran tire company technical types who serve as mentors.

That means only experienced engineers and chemists are making decisions about the tires you sell. These seasoned vets constantly make running changes in tire technology to improve such things as noise, vibration and harshness, as well as handling characteristics, tread life, braking, water dispersion, and even better gas mileage. And the process never stops.

In this article, the first of four, you’ll get a dose of “plain English” explanations about tire pieces and parts. Tire buyers count on you to explain the complexities of a tire. With all of the advanced technology we’ve seen in recent years, and all of the accompanying acronyms, we’ve lost touch with the basics. How, after all, can you explain to a customer why a tire performs as it claims if you don’t understand more than the acronyms?

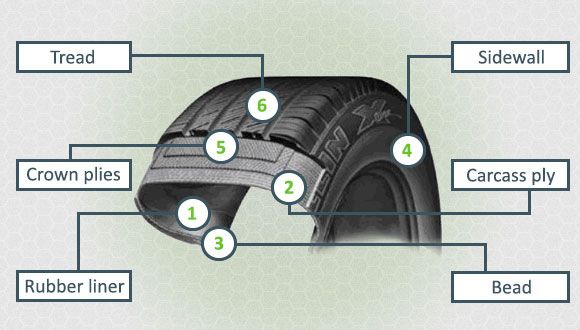

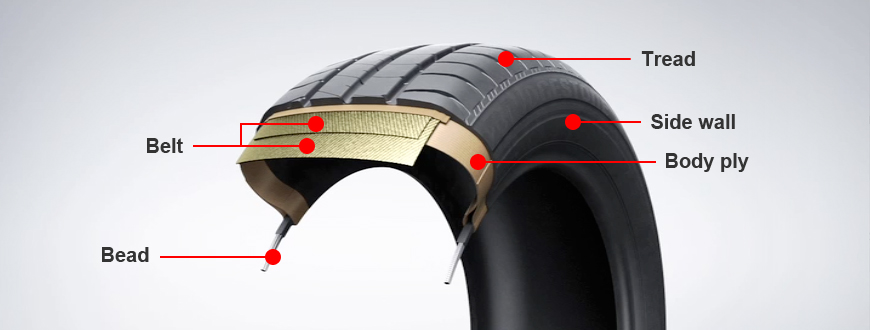

A tire must not only look like it can get the job done; it must have the guts to perform the tough work it is asked to do. It must equal or exceed the design intention of every engineer who gives it life. And it must do so with its basic components: the bead, the sidewall, the belt package, the tread compounds and the tread design.

We’ll begin with a close look at the bead and sidewall areas of the tire. In future issues, we’ll address the other primary components.

The Bead Area

In the simplest language, the bead is a loop of high-tensile steel cable coated with rubber. Its primary mission is to provide the muscle a tire needs to remain seated on the rim flange and to pass along the forces between the tire body plies and the wheel.

Sometimes called the bead bundle, the bead must also be tough enough to handle the forces encountered by tire mounting machines.

Typically, a bead bundle is comprised of about one pound of large monofilament steel cords. The cord is coated with rubber and then wound into a properly sized loop based on the designed wheel diameter. The resulting bundle is then wrapped with a ribbon of rubber-coated ribbon material. Depending on the tiremaker or the product, the resulting bead hoop can be square, rectangular, octagonal or oval in shape.

Of course, it’s impossible to talk about the bead bundle without mentioning the tire’s body plies. Keep in mind that body plies run from bead to bead, looping down and around the bead bundle, which holds them in place.

In most cases, a passenger tire casing has one or two body plies, which can be made of polyester, steel or nylon. We’ll talk more about the casing later, but it’s important to note how the bead bundle fits into the overall tire design as it relates to body plies.

At The Apex

Next, let’s look at the bead apex filler – a hard or soft rubber compound that envelopes the bead and extends up into the sidewall. If the tire is a high profiler designed to provide a boulevard ride, the bead apex filler will be softer. However, on a low-profile ultra-high performance tire, the bead apex will be much harder and extend further into the upper sidewall area for added stiffness.

Generally speaking, a low-profile tire with a stiffer sidewall (and a harder bead apex filler) rides rougher but delivers better handling. A softer sidewall (with a softer compound bead apex filler) provides a softer, more comfortable ride.

Another function of the bead apex filler is to create a smooth contour for the body plies around the bead wire in the lower sidewall area.

The remaining component in the bead area is the bead chafer, or chafer strip. Its mission is to protect the bead area from rim chafing, mounting/dismounting damage and to prevent the tire from rotating on the rim. Chafer strips are made of a hard, durable compound rugged enough to withstand the forces working against it.

Chafer strips are made of a hard, durable compound rugged enough to withstand the forces working against it.

In quick review, the bead area of any tire is made up of a bead bundle, a bead apex filler and a bead chafer. Each has a separate job, yet each piece must rely on the other to function the way tire construction engineers intended.

The Sidewall

Now that we have the tire firmly attached to the wheel, the bead wire well protected, and the body plies safely wrapped around the bead, let’s move up to the sidewall.

Tire sidewalls vary in thickness from the shoulder area to the bead area. In the thinnest part, typically in the middle to upper area, most sidewalls are between 6- and 15-mm thick – about 1/4- to 5/8-inch thick. The differences are dependent upon tire application – thinner for ride comfort street tires (S- or T-rated), thicker for off-road light truck tires that require significantly stronger sidewalls.

You should also know that the sidewall and bead areas of a tire represent about 30% of a tire’s total weight. Multiple sidewall plies are typically a blend of natural and synthetic (butadiene) rubber.

Multiple sidewall plies are typically a blend of natural and synthetic (butadiene) rubber.

Keeping that in mind, a sidewall’s primary mission is to transmit force from the ground to the vehicle via the wheel. Inflation pressure holds the sidewall out where it’s supposed to be, allowing it to help carry the load.

The sidewall is also responsible for maintaining lateral stability as hard cornering and/or braking forces are transmitted through the sidewall to the bead.

Engineering at Work

As these forces push and pull their way though the sidewall and bead area, we see some of the finest engineering in the world at work. The body plies, always under compression, are assembled in such a way that the forces working against them are passed to the vehicle via the strong contact between the bead wire, the chafer strip and the wheel’s rim flange.

All of this assumes that the tires are properly inflated. Driving on an underinflated tire results in unwanted sidewall deflection. Such deflection can be more than the tire was designed to handle, resulting in too much heat generating flexing and life-shortening possibilities for the tire over time.

Such deflection can be more than the tire was designed to handle, resulting in too much heat generating flexing and life-shortening possibilities for the tire over time.

Acceleration also does its best to shorten tire life. Step on the accelerator, and you pull the tire components forward, bending and twisting them in the process (If you’ve ever witnessed a rear drag race tire work in slow motion, you’ve seen an extreme example of this phenomenon.). Step on the brakes, and the forces at work stress the rubber in the opposite direction.

Ultra-high performance tires handle these assignments well because of compounding and design technologies employed in the tread area, which we’ll talk about in a future Tire Tech.

To be clear, it is the sidewall and bead areas that deliver all of the real performance and driver comfort.

Sidewalls also face another force: the elements. Weather and ozone can cause cracking and weather checking. That’s why a tire’s sidewall is loaded with a host of materials like anti-oxidants, anti-ozonants and paraffin waxes.

Bounce-Back Factor

The ideal bead and tire sidewall combination offers low hysteresis (for low energy consumption), good tear strength and low heat generation. These properties and characteristics contribute to low rolling resistance, which, in turn, contributes to better gas mileage.

In tire-speak, low hysteresis represents the ability of a tire to return to its normal shape after encountering severe deflection or opposing force. Think of dropping a super ball (low hysteresis) and a ball of Play-Doh (high hysteresis). The super ball bounces very high because it doesn’t absorb the energy. Play-Doh doesn’t bounce because it absorbs all of the energy.

The rubber used in tires must fall somewhere in between, yet be a lot stronger than Play-Doh. Its job is to absorb some of the energy, which is converted into heat.

A tire’s innerliner, one of the first building steps in the production of a radial tire and the last item we’ll talk about in this installment, functions like an inner tube and is the unseen part of a tire and its sidewall.

An innerliner is made up of low-permeability rubber laminated to the inside of a radial tire. Its mission: to keep air in the tire. Typically, it is made of butyl rubber, which is not reactive with oxygen. A small amount of rubber (synthetic isoprene) is added to allow the innerliner to adhere to the body plies during vulcanization.

In the next Tire Tech, we’ll explore the role of the belt package. If you require further elaboration on what we’ve talked about in Part 1, please drop me an e-mail at [email protected].

Mini Glossary of Basic Tire Terms

Bead: The tire part made of steel wires, wrapped or reinfored by tire cords and shaped to fit the rim flange. The bead anchors the body cords of the tire to the rim so that they may resist external and internal (pneumatic) forces.

Bead area: That part of the tire structure surrounding and in the immediate area of the bead wire hoop. Consists of fabric components and shaped rubber parts to provide a tight fit to the contour of the rim flange, resistance to chafing at rim interface and flexing support for the lower sidewall.

Bead filler (apex): A rubber compound filler smoothly fitting the body plies to the bead.

Bead heel: Rounded part of bead contour, which contacts rim flange where the flange bends vertically upward.

Bead reinforcement: A layer of fabric located around the bead area outside of the body plies to add stiffness to the bead area.

Bead separation: Failure of bonding between components in the bead area.

Bead wrap: Subsequent to forming of the bead, for some manufacturers, the bead is wrapped with a fabric similar to friction tape.

Body (carcass; casing): The rubber-bonded cord structure of a tire (integral with bead) containing the inflation-pressure-generated forces.

Body ply turnup (turnup plies): Ends of body plies in a tire, which are wrapped under the bead wire bundle and extend up the sidewall.

Chafer: A layer of rubber compound, with or without fabric reinforcement, applied to the bead for protection against rim chafing and other external damage.

Flange: The upward curved lip of a wheel rim, which contacts the outer surface of the tire bead.

Flex cracking: A cracking condition of the surface of rubber resulting from repeated bending or flexing.

Flipper: A partial ply wrapped around the bead coil but not extending the full height of the sidewall.

Innerliner: Innermost layer of rubber in a tubeless tire, which acts as an inner tube in containing the air.

Innerliner separation: Separation of tire innerliner from tire carcass, resulting in air loss.

Ply turn-up: The portion of body plies passed around the bead coil.

Sidewall: The portion of either side of the tire that connects the bead with the tread.

A damaged sidewall can be dangerous and costly. Learn what sidewall damage is, how to prevent it, and when you should replace your tires.

If you’re like most drivers, you probably don’t give much thought to your car’s tires until there’s a problem.

And while a tire blowout or flat may be the most obvious indication that it’s time for a new set of rubber, other types of damage can also signal the need for a replacement.

One such type of damage is sidewall wear or damage. So, what is sidewall damage, and when should you replace a tire because of it? Read on to find out.

A sidewall tire damage is what it sounds like; damage to the tire’s sidewall, meaning the damage is on the side of the tire and not the tire tread. Damage to the tire’s sidewall is not repairable in most cases.

You can often spot one by seeing a deep scratch or a bubble on the tire’s sidewall. This can come from a small accident or if you drove too close to the road’s curb.

It can also happen because of sticks or other sharp things along the road. A sidewall tire damage is really bad to drive around with, and now we will explain why.

No, a tire sidewall damage is not safe to drive with. The sidewalls of the tires are much more sensitive than the tread area. In many cases, the damage is damaging the whole structure of the tire, and it can cause it to blow at any moment.

The sidewalls of the tires are much more sensitive than the tread area. In many cases, the damage is damaging the whole structure of the tire, and it can cause it to blow at any moment.

This does also depend a little bit on how big the scratch or damage is. If the scratch is small and super-shallow and does not reach the threads, it is probably not something you should worry too much about.

A rule of thumb for determining how much sidewall tire damage is too much is that if you can see the threads in the damage, it is definitely time to replace the tire.

The threads are often located 1/8″ to 3/16″ (3mm to 4.5mm) into the tire, but to determine exactly if you need to replace the tire or not, you need to look at the damage itself.

If there is an air-bubble on the tire’s sidewall, you need to replace it straight away because there is a big risk that it will blow at any moment.

To be sure that nothing serious will happen to the tire, you should let an expert look at the damage.

Find a repair shop that is not selling tires and ask them. If you go to a repair shop that is selling tires, it is a big chance that they will want you to buy new tires.

A sidewall tire damage that reaches the threads should never be repaired because it damages the tire’s whole structure.

If the tire’s sidewall has a bubble, it is not fixable either, and small punctures should either not be repaired.

The only time you can glue together a sidewall tire damage if it is a super shallow scratch that is not reaching the threads.

However, if the scratch or damage is this shallow, there is no point in gluing it either, so I would say that you should never repair a sidewall tire damage.

RELATED: Can You Patch a Hole in the Sidewall of a Tire?

There are a lot of things that could cause tire sidewall damage. Mostly it is because of sharp objects you were hitting with the sidewall of the tire by accident. It can also be caused by age or driving around with too little air pressure in the tires.

It can also be caused by age or driving around with too little air pressure in the tires.

Here are the common causes of tire sidewall damage:

If you change the tires on the drive wheels, you should change both tires because the different tire diameters will stress the transmission.

If you replace the tires on the rear of a front-wheel drive car, for example, you can replace just one tire.

If you have a 4wd car, it is always recommended to replace all four wheels because different tires’ diameters can cause stress to the differential or transmission. The best way to find out is to ask your authorized dealer if you can replace just one tire on your specific car model.

No, sidewall tire damage is usually considered self-inflicted damage and not a manufacturer problem, and therefore not covered under warranty in most cases.

But if you want to be sure, you can always ask or read your warranty documents carefully because there are cases where you have a special car warranty.

A car tire typically has a sidewall that is between 1/4″ to 5/8″ (5 to 15 mm) thick. However, this can vary depending on the specific tires that are being used. Some tires may have thicker or thinner sidewalls, depending on their design and intended purpose.

For example, race car tires often have very thin sidewalls to help improve grip and handling. Likewise, some off-road tires may have thicker sidewalls to help protect against punctures from rocks or other debris.

Tire sidewall damage is never OK. A bulge or tear in a tire’s sidewall means that the internal tire structure has been compromised, and the tire should be replaced immediately. Driving on a sidewall damaged tire can cause it to blow out, resulting in a serious accident.

Was this article helpful?

YesNo

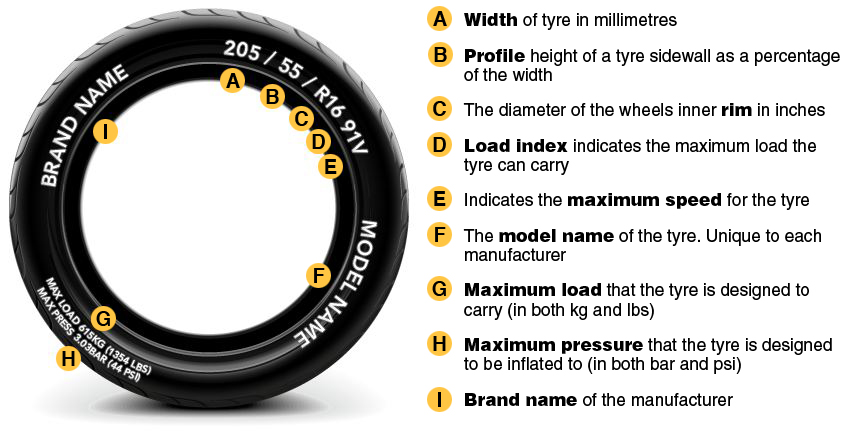

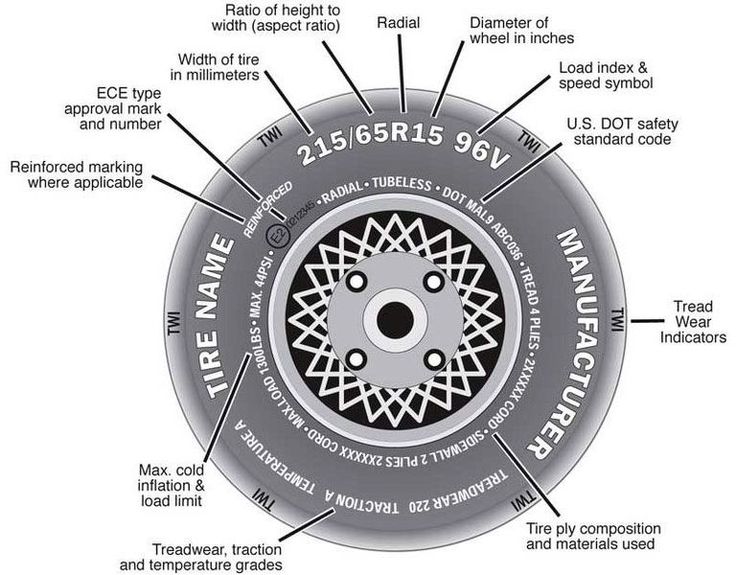

Which tires to buy? Should I change tire size? At the beginning of the next season of “re-shoeing”, these and other issues related to the choice of tires are still of interest to thousands of car owners. Portal "AutoVzglyad" will give some tips that will surely help understanding the general dependencies in this matter.

Sergey Sokolov

In the context of a myriad of product options, no one can ever be sure of the unequivocal correctness of the choice. When recommending something to you, 95% of “advisers” pursue one goal - to convince themselves of the correctness of their own decision. Aggressive imposition is typical for people who are insecure, doubting their choice. On the contrary, listen to a person who criticizes his own things: most likely he is telling the truth.

The size recommended by the manufacturer is a good universal choice, but ruthless tuning cannot be stopped, many people really want wide tires. At the very least, you should not go much beyond the recommended width. It is not necessary to put tires wider than the rear tires - handling will suffer critically. You can’t put different tires on an all-wheel drive car, but if you really want to, use a tire calculator to ensure that the rolling radii of the front and rear wheels are equal. The installation of low profile tires will lead to an increase in the speedometer readings and an improvement in dynamics, and vice versa - when driving on a high profile, there will be an impression of some loss of power. There are a number of other nuances.

At the very least, you should not go much beyond the recommended width. It is not necessary to put tires wider than the rear tires - handling will suffer critically. You can’t put different tires on an all-wheel drive car, but if you really want to, use a tire calculator to ensure that the rolling radii of the front and rear wheels are equal. The installation of low profile tires will lead to an increase in the speedometer readings and an improvement in dynamics, and vice versa - when driving on a high profile, there will be an impression of some loss of power. There are a number of other nuances.

Photo by clickmountairy.com

The wider the tire and the lower the profile, the less the tire is prone to lateral deformation, the less its “steer”, which means that such a tire keeps a straight line more stable, but the steering wheel will become more “sharp”, some of these are tires. In a sharp turn, wide tires cling to the road for longer, but unlike the “normal” one, they break into a skid sharply, jerkily.

Wide tires are more "nervous" in asphalt ruts, and this is explained by the balance of forces. On an inclined part of the track, different sides of the tire have different rolling resistance due to different loads. The total resulting force tries to turn the wheel, and the wider the tire, the greater the "shoulder of force" and, accordingly, the stronger the impact.

The well-known feature of wide tires is that they "eat" the edges - a consequence of the laws of geometry. The outer and inner beads of the tire travel different paths in the turn due to different distances from the center of the turn. The wider the tire, the greater the difference in paths, and the greater the deformation and microslip of the tread along the edges of the contact patch, the wear in these areas increases. Tread slip cannot be seen, but can be heard in winter when driving on packed snow. Even with very slow, so to speak, creeping movement, the creak of snow in a turn will be much stronger than when moving in a straight line.

Photo canadiantire.ca

758923

Practically derived law confirms the laws of physics and narrow-minded instinct: tires with thin beads help save fuel, but are always less resistant to sidewall breakdown. Manufacturers' assurances about the "supernanomaterial" of the cord - we skip. Bottom line - tires with a thin sidewall can only be recommended for driving on good roads.

Contrary to manufacturer claims, directional tires provide a very slight increase in hydroplaning initiation. It is logical that tires with a rough pattern and wide grooves “float” less.

Tire noise is difficult to predict from the tread pattern. Sometimes a developed tread suddenly turns out to be very quiet, and a relatively smooth, road tread makes disgusting howls.

Photo wheelworks.net

When choosing a tire, it is important to pay attention to the quality of rubber. The entire surface of a good tire should be noble-shiny, free of air bubbles, with clear inscriptions. Tire balancing "to zero" should be achieved with a small number of weights. Sometimes, after changing tires, the car pulls to the side, or the zero position of the steering wheel shifts. If the pressure is normal, then the reason is the so-called power heterogeneity of the tires: one of the front tires is stiffer than the other, and rolls harder. In this case, try swapping the front and rear wheels. Should help.

Tire balancing "to zero" should be achieved with a small number of weights. Sometimes, after changing tires, the car pulls to the side, or the zero position of the steering wheel shifts. If the pressure is normal, then the reason is the so-called power heterogeneity of the tires: one of the front tires is stiffer than the other, and rolls harder. In this case, try swapping the front and rear wheels. Should help.

396828

HISHISHIKS Wait for reduction and transfers to the PPS, and drivers - new problems

425071

traffic cops are waiting for reduction and translations to the PPS, and drivers - drivers - drivers - drivers - drivers - drivers - drivers - drivers - drivers - drivers - drivers - drivers - drivers. new problems

425071

0009

tire properties. Let's see what are the pros and cons of a soft sidewall, and also what good summer tires with a hard sidewall are, and what are its disadvantages.

Let's see what are the pros and cons of a soft sidewall, and also what good summer tires with a hard sidewall are, and what are its disadvantages.

Even if the tire tread rubber is soft, the side of the tire can be quite hard, in some cases specially reinforced - summer tires with reinforced sidewall. The stores offer tire models of various thicknesses and sidewall stiffness, so it is better to feel each tire with your hands in order to buy exactly what you need. Tire manufacturers strive to create the sidewall of their wheels in such a way that with a minimum thickness of the sidewall, they have maximum strength and comfortable stiffness. Summer tires with a rigid sidewall have their own advantages and disadvantages.

The stores offer tire models of various thicknesses and sidewall stiffness, so it is better to feel each tire with your hands in order to buy exactly what you need. Tire manufacturers strive to create the sidewall of their wheels in such a way that with a minimum thickness of the sidewall, they have maximum strength and comfortable stiffness. Summer tires with a rigid sidewall have their own advantages and disadvantages.

Soft sidewall tires are found in tire shops in various price ranges. The soft sidewall on tires can be either on a tire with a soft or a hard rubber compound. What does the soft sidewall of the tire give and what threatens its use? Despite its softness, the tire sidewall can be strong enough for operation not only in urban conditions, but also in highway conditions, where special reliability is required from the tire. It must be remembered that if you choose low-profile tires, then it is better not to consider them with a soft sidewall, otherwise the rubber can quickly fail, tearing the side of the tire against the wheel disk on asphalt breaks. For the track, it is better to choose tires with a sidewall of medium softness, you will get reliable operation with virtually no loss of comfort. As with anything, there are pros and cons to soft sidewall tires.

What does the soft sidewall of the tire give and what threatens its use? Despite its softness, the tire sidewall can be strong enough for operation not only in urban conditions, but also in highway conditions, where special reliability is required from the tire. It must be remembered that if you choose low-profile tires, then it is better not to consider them with a soft sidewall, otherwise the rubber can quickly fail, tearing the side of the tire against the wheel disk on asphalt breaks. For the track, it is better to choose tires with a sidewall of medium softness, you will get reliable operation with virtually no loss of comfort. As with anything, there are pros and cons to soft sidewall tires.

Car owners are recommended: